I will not worry about winning or losing rating points. I will only concern myself with learning from each game that I play.

Paul Powell, The Fighting Dragon: How to Defeat the Yugoslav Attack (2016), 18.

Before the end of the Seattle Seahawks historic loss to the Green Bay Packers last Sunday, I went online to play a few games of blitz. My play was angry and motivated by the desire to inflict misery upon my opponents. The Seahawks are my team and they suffered their worst loss in half a decade. I like the Packers, too. They are my second favorite team, but I don't like them thrashing my Seahawks.

A few of my angry chess games were successful victories, but others aggravated my misery facing the Seahawks' loss. I went back into the television room to watch the end of the slaughter. I tried turning the sound off, thinking the loss would be less painful without the voices of Troy Aikman and Joe Buck.*

After the football game, I frantically played chess late into the night. My rating suffered. Through the course of the week, I played game after game with more focus on getting my online blitz rating back above 1900 than on learning anything or even enjoying the game. From a rating in the mid-1900s before the Seahawks catastrophe, I managed to drop to the low 1800s several times before climbing back to the 1880s.

The Seattle Seahawks had another game Thursday night. A few terrific plays gave them the points they needed while the defense kept the Los Angeles Rams from scoring more than a field goal. The Seahawks clinched their third division title in the past four years!

I played about an hour of blitz after the game, but efforts to reach 1900 remained futile. I also spent some time reviewing a few of the week's games. Friday morning, I reviewed Thursday night's games and then played a few more.

When the last game began, I saw that my opponent was rated 2023 (my peak of 2005 was achieved last February). Some advice came to mind. Last weekend I started reading Paul Powell,

The Fighting Dragon (see epigraph above). I said to myself, "okay, let's see what I can learn." My French Defense transposed quickly into a closed Sicilian, an opening that often gives me difficulty. I offer the game below with some light annotations.

Internet Opponent (2012) -- Stripes,J (1889) [B24]

Live Chess Chess.com, 16.12.2016

1.e4 e6 2.Nc3 c5 3.g3 Nc6 4.Bg2

My database shows that I have been on the Black side of this position 28 times with eighteen losses and ten wins. The sole over the board game was played twenty years ago. I have played many moves here, most often Nge7 or Be7.

4...b6?!

A new move for me in the position. A better plan for Black is to play Rb8 and then b7-b5. I learned this idea while reviewing several games in the database. My intent with b7-b6 failed to take account of the idea to fight for queenside space and activity, but aimed to oppose White's light-squared bishop with my own. I was attentive to the potential for tactics that could threaten my bishop or rook along the a8-h1 diagonal. I addressed these possibilities through cumbersome means.

4...g6 is preferred by top players. I have played it once.

5.d3 Bb7 6.Nge2

6.f4 g6

6...Nge7 7.Nge2 d5 8.exd5 exd5 9.0–0 d4 and Black won in 34 moves Heimrath,R (2321) -- Chandler,P (2238), Schwaebisch Gmuend 2001.

7.Nf3 Bg7 8.0–0 Nge7 9.g4 h5 and Black won in 52 moves Seirawan,Y (2635) -- Kamsky,G (2686) playchess.com INT 2006.

6...a6

Preparing b6-b5.

6...h6 7.Be3 Nf6 8.h3 Bd6 9.Qd2 Rc8 and drawn in 33 moves Meitner,P -- Heral,J, Vienna 1873.

7.0–0 Qc7

Protecting the bishop.

8.h3

8.Bf4 e5 9.Be3

8...Nge7 9.Be3 h5

I might castle queenside.

10.Qd2 g6 11.f4 Bg7

I would like to post a bishop or knight on d4, although my opponent likely will not allow that. There is also a possibility of playing d5 with the support of a rook on d8. Such a thrust in the center is a normal way of meeting White's obvious plan to expand on the kingside.

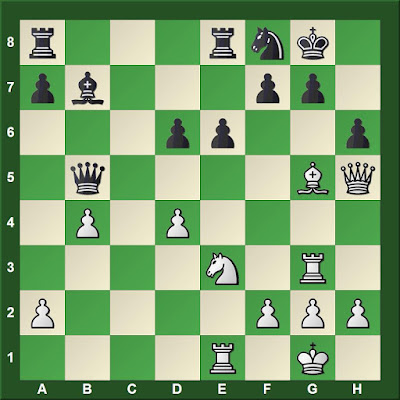

White to move

12.e5

My bishop is temporarily immobile. Even so, this move may reveal a faulty plan on White's part. He might consider preparing f4-f5. Here, perhaps, my ninth move may have served to slow his kingside expansion.

12...Nf5

I might like to exchange knight for bishop and then force an exchange of center pawns in order to open the position somewhat. On the other hand, maybe I should castle first.

13.Ne4 d5

White's knight attacks two important squares.

14.exd6 Nxd6 15.Nxd6+ Qxd6 16.Nc3 Qc7 17.Rae1 0–0

Was 17...O-O-O worth considering? I did think about it.

18.Kh2 Rad8 19.Ne4 Nd4 20.c3 Nf5

Still after that bishop.

White to move

21.Bf2

White's pawns are more mobile.

21...Bxe4

The queen needs a role other than defending a bishop. My strategic errors in the opening have given me a slightly worse position.

22.Bxe4 Nd6 23.Bg2 Qd7

Intending Nc4.

24.Qe2 b5?

White to move

25.Rd1

White should have lopped off the c5 pawn.

25...Nf5 26.Be4

The c5 pawn remains

en prise.

26...Ne7 27.g4 hxg4 28.hxg4 Qc7

Finally, I defend the c5 pawn. White has achieved an advantage in space on the kingside, rendering his pieces more mobile and offering more flexibility to probe for weaknesses. The bishop pair also could be put to use. White's rooks and queen have two ranks for maneuvering. Black is strategically lost, it seems to me.

29.Bg3 Qb6

Obviously, I cannot allow f4-f5 to unleash a discovery on my queen. When I am losing many blitz games in sequence, it often stems from being oblivious to these simple threats. Sometimes single-minded focus on my own attack leads to such blindness. That is not the case here. My pieces are too poorly coordinated to generate threats.

30.Kg2 Nd5 31.Rh1 Bf6

Intending to play Kg7 and contest the h-file with my rooks.

32.g5

White drives the bishop back. However, this move reduces White's flexibility for attacking with pawns, as did his 12th move.

32...Bg7

White to move

33.Bxd5?

Now, finally, I get some play on the d-file.

33...Rxd5 34.Qg4 Qc6

Setting up a simple discovery. Two can play this game of checking the opponent's eyesight.

35.Kf2 b4 36.Qh4 Rfd8

Otherwise 37.Qh7#. Of course, I want both rooks on the d-file anyway.

White to move

37.c4?

White practically concedes the game. White's advantage has dissipated since 33.Bxd5, and now Black gains a decisive advantage. 37.d4 seems much better, offering chances for both sides.

37...Rxd3 38.Rxd3 Rxd3 39.Re1

At this point, I realized that the game had turned my way. We were both running low on time, however. In blitz, the clock often decides matters after a complex struggle.

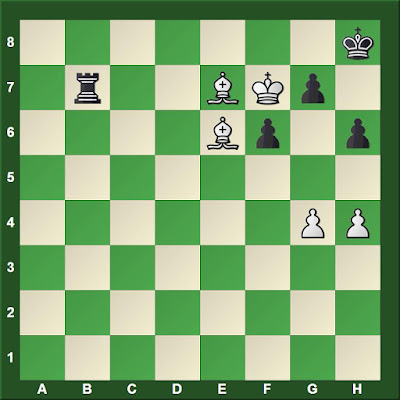

Black to move

39...Qf3+ 40.Kg1 Qxg3+ 41.Qxg3 Rxg3+ 42.Kf2 Rd3 43.b3 Bd4+ 44.Ke2 Re3+ 45.Kd2 Rxe1 46.Kxe1 Bc3+

46...Be3 is obviously much better. Both players were down to fifteen seconds. I started moving much faster than my opponent with easier premoves. From here to the end of the game, I used less than five seconds, while my opponent used ten.

47.Ke2 Bd4 48.Kf3 Kg7 49.Ke4 Bb2 50.Kd3 Bd4 51.Kc2 f6 52.Kd3 fxg5 53.Ke4 gxf4 54.Kxf4 Kf6 55.Ke4 g5 56.Kf3 e5 57.Kg4 Kg6 58.Kf3 Kf5 59.Ke2 g4 0–1

Although played before 8:00 am, this blitz game was my last for the day.

*It is interesting that Seahawks fans and Packers fans have independently launched protests against these two broadcasters, accusing them of bias against their teams.