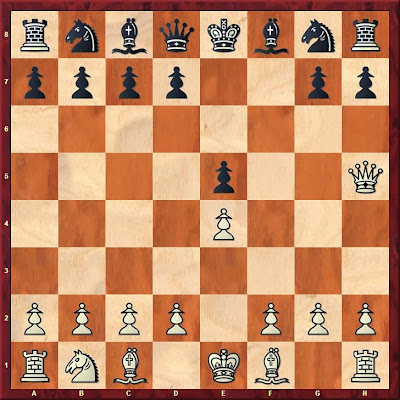

Black to move

Greco's explorations of this queen foray appear in the Paris (1625) and Orléans (n.d.) manuscripts. Peter J. Monté notes in The Classical Era of Modern Chess (2014) that Orléans was likely copied from the Paris MS (339), although some errors were corrected. Part II of this book, "Openings and Games of the Classical Era of Modern Chess" (439-530), has been an indispensable resource.

I have contended that Greco's games are poorly known, even by those who think they have studied all of them. Most players access these games through ChessBase or websites such as chessgames.com (currently 90 games). The latter has more Greco games, but both offer shorter versions of what is available in such old books as "Professor Hoffmann" [Angelo Lewis], The Games of Greco (1900), and William Lewis, Gioachino Greco on the Game of Chess (1819). These shorter versions miss the best of Greco's analysis.

A couple of years before the earliest version of what eventually became ChessBase Mega, David Levy and Kevin O'Connell made an effort to record all known games up to 1866 in Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Volume 1 1485-1866 (1981). They offer 77 Greco games, many annotated. These are extracted from Hoffmann's text. As with Lewis before him, Hoffmann buried the best analysis in the variations, which sometimes are much longer than the main game. Levy and O'Connell continue this practice.

The games in ChessBase come close to representing these abbreviated "main games" sans the variations. If the longest variation of each game were the main game instead, what most chess players know of Greco would be substantially enriched. Here I offer improved versions with notes. The notes show other lines that appear in Greco's manuscripts and in Hoffmann.

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Paris, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6

ChessBase Mega 2020 has four games with this move. Three are Greco's. The other was a fighting draw played in Germany in 2010. No rating is given for the player of Black, while White's is slightly over 2000.

4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+

All of Greco's games reach this point. The analysis continues with lines that follow all three of Black's legal moves.

5...Kd8

5...Kxf7 6.Ng5+ Ke8 7.Nxe4 matches a game in CB Mega 2020 and also appears in the Paris MS.

I have contended that Greco's games are poorly known, even by those who think they have studied all of them. Most players access these games through ChessBase or websites such as chessgames.com (currently 90 games). The latter has more Greco games, but both offer shorter versions of what is available in such old books as "Professor Hoffmann" [Angelo Lewis], The Games of Greco (1900), and William Lewis, Gioachino Greco on the Game of Chess (1819). These shorter versions miss the best of Greco's analysis.

A couple of years before the earliest version of what eventually became ChessBase Mega, David Levy and Kevin O'Connell made an effort to record all known games up to 1866 in Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Volume 1 1485-1866 (1981). They offer 77 Greco games, many annotated. These are extracted from Hoffmann's text. As with Lewis before him, Hoffmann buried the best analysis in the variations, which sometimes are much longer than the main game. Levy and O'Connell continue this practice.

The games in ChessBase come close to representing these abbreviated "main games" sans the variations. If the longest variation of each game were the main game instead, what most chess players know of Greco would be substantially enriched. Here I offer improved versions with notes. The notes show other lines that appear in Greco's manuscripts and in Hoffmann.

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Paris, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6

ChessBase Mega 2020 has four games with this move. Three are Greco's. The other was a fighting draw played in Germany in 2010. No rating is given for the player of Black, while White's is slightly over 2000.

4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+

All of Greco's games reach this point. The analysis continues with lines that follow all three of Black's legal moves.

5...Kd8

5...Kxf7 6.Ng5+ Ke8 7.Nxe4 matches a game in CB Mega 2020 and also appears in the Paris MS.

White to move

6.Nxe5 Nf6

6...Qxe5 7.Re1 Qf6 8.Re8# Orléans. Game XXI, var. A in Hoffmann. This line ends with the same checkmate that can be found in one of the Greco selections in CB Mega 2020.

7.Re1 Qf5 8.Bg6

6...Qxe5 7.Re1 Qf6 8.Re8# Orléans. Game XXI, var. A in Hoffmann. This line ends with the same checkmate that can be found in one of the Greco selections in CB Mega 2020.

7.Re1 Qf5 8.Bg6

Black to move

8...Qe6

8...hxg6 9.Nf7# Game XXI, var. B in Hoffmann; Paris and Orléans MSS.

9.Nf7+ Ke8 10.Nxh8+ hxg6 11.Rxe6+ dxe6 12.Nxg6 1-0

8...hxg6 9.Nf7# Game XXI, var. B in Hoffmann; Paris and Orléans MSS.

9.Nf7+ Ke8 10.Nxh8+ hxg6 11.Rxe6+ dxe6 12.Nxg6 1-0

Black to move

This game and its variations appear in Paris MS (1625) XXXIII; Orléans MS XXII. The game is XXI, var. C in Hoffmann.

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Paris, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6 4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+ Ke7

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Paris, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6 4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+ Ke7

White to move

Greco considers every legal move for Black after the bishop check.

6.Re1 Qf4 7.Rxe5+

6.Re1 Qf4 7.Rxe5+

Black to move

Here, also, Greco considers every legal move for Black.

7...Kxf7

7...Kd8 Paris MS (1625) XXXIV. 8.Re8# This game appears in ChessBase Mega 2020.

7...Kf6 8.d4 Qg4 9.Bh5 Paris MS XXXIV.

7...Kd6 8.Rd5+ Kc6 9.Nd4+ Paris MS (9.Ne5+ Orléans MS)

8.d4 Qf6 9.Ng5+ Kg6 10.Qd3+

7...Kxf7

7...Kd8 Paris MS (1625) XXXIV. 8.Re8# This game appears in ChessBase Mega 2020.

7...Kf6 8.d4 Qg4 9.Bh5 Paris MS XXXIV.

7...Kd6 8.Rd5+ Kc6 9.Nd4+ Paris MS (9.Ne5+ Orléans MS)

8.d4 Qf6 9.Ng5+ Kg6 10.Qd3+

Black to move

10...Kh5

10...Kh6 11.Nf7# is given as the main line in Levy and O'Connell. Hoffmann, game XXII.

An essential aspect of Greco's technique in dealing with the horrid positions for which he is well-known is to seek to improve the losing side's defenses. When only the shortest versions of these games are known, this technique is hidden.

11.Nf7+

11.g4+ is not attested by Monte, but is found in CB Mega 2020.

11.Nf3+ Kg4 (11...g5 12.Rxg5+) 12.h3# Orléans MS.

11...Kg4

11...g5 12.Rxg5+ Game XXII, var. B in Hoffmann.

10...Kh6 11.Nf7# is given as the main line in Levy and O'Connell. Hoffmann, game XXII.

An essential aspect of Greco's technique in dealing with the horrid positions for which he is well-known is to seek to improve the losing side's defenses. When only the shortest versions of these games are known, this technique is hidden.

11.Nf7+

11.g4+ is not attested by Monte, but is found in CB Mega 2020.

11.Nf3+ Kg4 (11...g5 12.Rxg5+) 12.h3# Orléans MS.

11...Kg4

11...g5 12.Rxg5+ Game XXII, var. B in Hoffmann.

White to move

12.h3+

Hoffmann writes, "Greco gives this move as mate, but this is obviously a slip, Black still having one square available" (65). Monte notes this error in Paris XXXIII (477).

12.Qg3# Monte notes that Greco overlooks this mate.

12...Kh4 13.Qg3# 1-0

This game appears in the Paris MS (1625) XXXIII. Also as Game XXII, var. A in Hoffmann.

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Orléans, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6 4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+ Ke7

5...Kxf7 6.Ng5+ Ke8 7.Nxe4 is found in CB Mega 2020

6.Re1

Hoffmann writes, "Greco gives this move as mate, but this is obviously a slip, Black still having one square available" (65). Monte notes this error in Paris XXXIII (477).

12.Qg3# Monte notes that Greco overlooks this mate.

12...Kh4 13.Qg3# 1-0

This game appears in the Paris MS (1625) XXXIII. Also as Game XXII, var. A in Hoffmann.

Greco,Gioachino [C40]

Orléans, 1625

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Qf6 3.Bc4 Qg6 4.0-0 Qxe4 5.Bxf7+ Ke7

5...Kxf7 6.Ng5+ Ke8 7.Nxe4 is found in CB Mega 2020

6.Re1

Black to move

6...Qf4 7.Rxe5+ Kd6

7...Kf6 8.d4 Qg4 9.Bh5 Game XXIII, var. A in Hoffmann.

7...Kd8 8.Re8# Paris MS (1625) XXXIV; Orléans MS. Game XXIII in Hoffmann. This version is in CB Mega 2020.

8.Rd5+ Ke7 9.Qe1+ Kxf7 10.d4 Qf6

7...Kf6 8.d4 Qg4 9.Bh5 Game XXIII, var. A in Hoffmann.

7...Kd8 8.Re8# Paris MS (1625) XXXIV; Orléans MS. Game XXIII in Hoffmann. This version is in CB Mega 2020.

8.Rd5+ Ke7 9.Qe1+ Kxf7 10.d4 Qf6

White to move

11.Ng5+ Kg6 12.Qe8+

Paris MS has an error here, corrected in Orléans.

12...Kh6 13.Nf7+ Kg6

Paris MS has an error here, corrected in Orléans.

12...Kh6 13.Nf7+ Kg6

White to move

14.Nxh8# 1-0

This game appears in the Orléans MS. Also Game XXIII, var. B in Hoffmann.

My view is that Greco's attacking technique against the best defense he found for Black is quite instructive. Of course, 2...Qf6 is a bad move, and 3...Qg6 is worse. Nonetheless, the simple refutations offered in the sample of these games in ChessBase Mega and on database websites have unjustifiably tarnished Greco's reputation. Much more of value exists in his model games than is generally believed.

This game appears in the Orléans MS. Also Game XXIII, var. B in Hoffmann.

My view is that Greco's attacking technique against the best defense he found for Black is quite instructive. Of course, 2...Qf6 is a bad move, and 3...Qg6 is worse. Nonetheless, the simple refutations offered in the sample of these games in ChessBase Mega and on database websites have unjustifiably tarnished Greco's reputation. Much more of value exists in his model games than is generally believed.