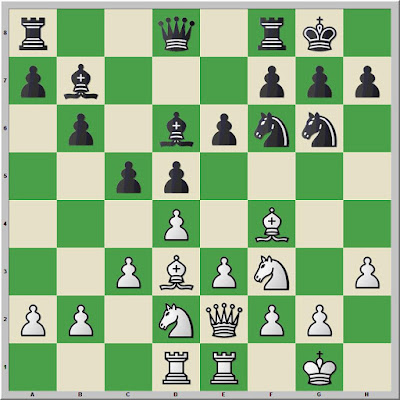

White to move

The key move, Nimzowitsch writes, is Nd5, "and the knight here placed we call the outpost; by which we mean a piece, usually a knight, established in an open file in enemy territory, and protected (of course by a pawn)" (32). This move provokes black to drive the knight back with c6, a move which weakens the d-pawn.A contrasting definition of outpost is given by David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld in The Oxford Companion to Chess (1992). In their definition, an outpost is a square, "guarded by a pawn but cannot be attacked by an enemy pawn, especially such a square on an open file" (285). That the square cannot be assailed by an enemy pawn is central to Peter Romanovsky's description of the "eternal knight". In Chess Middlegame Planning, trans. Jimmy Adams (1990), Romanovsky suggests conditions when a piece might be placed permanently on a weak point in the opponent's position:

And so the potential weakness of a square arises as a result of the impossibility of attacking it with pawns. However, such a square should only be considered a real weakness when an enemy piece, which it will not be possible to drive away or eliminate by an exchange, threatens to take up a position. (37)Such a position was reached in a game presented by Romanovsky, Izmailov -- Kasparian, Moscow 1931. After 25...Nd4, Black's knight is unassailable.

White to move

The knight does not sit on an open file, as Nimzowitsch's definition would lead us to expect. Romanovsky does not employ the term outpost, but highlights the concept through "weak squares" and the "eternal knight".Hooper and Whyld also refer readers to their entry on the concept of "hole", "a square on a player's third rank or beyond that cannot be guarded by a pawn" (175). The concept, they state originates from the writing of Wilhelm Steinitz. He writes in The Modern Chess Instructor (1889) that he first used the term in The International Chess Magazine (November 1886). In Steinitz, we find the concept of an outpost square, albeit without the term later used by Nimzowitsch:

...not alone the weakness on one single pawn but also that of one single square into which any hostile man can be planted with commanding effect, will cause great trouble, and often the loss of the game, and that by proper management of the pawns such points of vantage need not be opened for the opponent. (xxxix)Steinitz gives the opening moves 1.e4 e5 2.c4 as creating permanent weaknesses for White on d3 and d4, even anticipating Nimzowitsch's focus on open files: "A hole or a weak square are still more troublesome when the opponent is enabled to open the file on which they are situated for his queens and rooks" (xxxix).

The Lesson

Several of my students this past week were presented a lesson concerning outposts that I extracted from Michael Stean, Simple Chess (1978). Stean offers a nuanced definition: "a square at the forefront of your position which you can readily support and from where you can control or contest squares in the heart of the enemy camp," mentioning both a supporting pawn and that the opponent cannot attack the position with pawns (13). He offers five illustrative games with informative annotations. I selected one position from each game, presented the position to my students, and we played from there. Then we looked at the game as played.

In Stean's first illustrative game, Tal -- Bronstein, Tbilisi 1959, Black contested White's efforts to establish a knight on d5. When the knight went there anyway, it provoked a series of exchanges that led to a superior endgame for Tal. The second game, Benko -- Najdorf, Los Angeles 1963, offers a well-placed forward knight on f5 and an open h-file for White's heavy pieces.

White to move

Stean's selection shows a range of tactical opportunities that were facilitated through battles focused on outposts and concludes with Unzicker -- Fischer, Varna 1962 where Fischer successfully prevented Unzicker's efforts to deploy a knight to a d5 outpost.

*I am using the 1947 David McKay edition, translated by Philip Hereford and revised by Fred Reinfeld.