A Book Review

I heartily recommend this book. Studying five positions per week, as the author suggests, improves retention, and likely long-term benefits from study. Having raced through the book, I will be reviewing and deepening my study of many positions in the book over the coming months.

Engqvist’s 300 positions are selected from classical games, recent master practice, and compositions. Engqvist also includes some of his own most instructive losses. He is guided by a library of chess books, many years of playing, and experience coaching. The core idea of deep study of a limited number of positions developed from the way he was coached by Robert Danielsson while a young player. He studied positions from Ludek Pachman’s books on the middlegame and endgame.

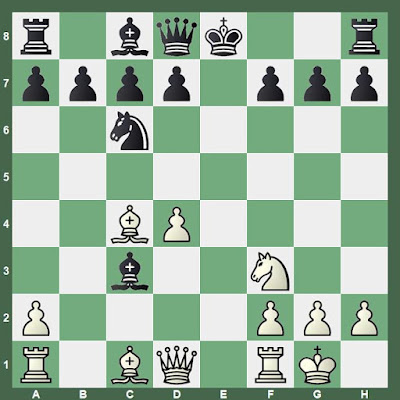

By way of illustration, he offers this composition by Paul Rudolf von Bilguer from 1843.

The positions that he chooses are interesting, challenging, instructive, and practical. Most of them were tested with chess players who subscribed to an email course where they were presented five positions per week. Rarely is a single move or short sequence the solution that one must find while examining the position. Only a few offer long computer solutions as in the Bilguer study. A considerable number of positions feature equal or near equal positions from games where strong moves and persistent maneuvers eventually provoked error.

Many of the positions are suitable for training with a study partner. Engqvist recommends playing both sides with another person, or against the computer. Teaching the position to someone else improves retention he notes, and in my experience also depth of understanding. My young students often vex me with moves that were not anticipated in master commentary or computer analysis. The positions in this book are excellent resources for coaches. The day that I acquired this book in February 2019, I took it to a lesson with my top student. We looked at six endgames and then the first position in the book (see "A New Book and a Morphy Game"). The next few weeks, this student and I will be playing some of the rook and queen endings.

Emphasis is on positional concepts, rather than tactical operations. The author notes that this emphasis distinguishes his book from Lev Alburt, Chess Training Pocket Book: 300 Most Important Positions and Ideas (1997), which emphasizes tactics. Alburt also limits the number of endgames. He states that becoming a "strong player" requires knowledge of 12 key pawn endings, not hundreds (9). These 12 are in his Pocket Book. Alburt's book is the second one that I list in "Ten Books to Achieve 1800+".

Some positions in 300 Most Important Chess Positions are surprising, such as White’s second move in the English Opening, Sicilian Reversed.

But this position is placed alongside others (both English Opening and Sicilian Defense) with references to several games played by top players. There is plenty of study material in these games. I might also note that Engqvist’s opening choices reflected in the positions chosen offer more variety than those in another collection of 300 positions that I’ve spent time working through: Rashid Ziyatdinov, GM-RAM: Essential Grandmaster Knowledge (2000). Ziyatdinov’s positions stem from games where 1.e4 is the overwhelming choice.

An instructive sequence of positions that I found highly motivating began with Bologan,V.--Frolov,A., Moscow 1991, a Sicilian Defense, then in a variation continued with Anand,V.--Illescas Cordoba,M., Linares 1992 and reference to Karpov,A.--Kasparov,G., Moscow 1985. It continued with Bologan--Frolov for two more positions, then Marin,M.--Korneev,O., Capo d'Orso 2008 takes us through moves 2-4 through three positions in the English Opening, Sicilian Reversed.

The first position in the book is slightly less surprising, but with two book moves played by Adolf Anderssen and Paul Morphy, as well as many other players before and since, Engqvist’s preference for Morphy’s choice provokes reflection.

As I consider Morphy’s 9.Nc3 in the Evans Gambit or Mihai Marin’s view that after 1.c4 e5, 2.g3 is the most precise, I am reminded of my tendency to blitz out opening moves by rote and only begin thinking after an inaccuracy. Engqvist’s positions from very early in the game should help me to develop better habits. Thinking should begin before the first move, even if positions at move 10 are well-studied.

There are positions in this book that I have used with students for many years and there are positions that are wholly new to me. There are many positions with several pages of analysis and variations. There are positions that should be drawn, but one player was able to present sufficient difficulties to provoke error.

Ziyatdinov advocates memorizing the 56 games from which he draws the middlegame positions; Engqvist is more selective in games that he suggests the student commit to memory. Schulten -- Morphy, New York 1857, a King's Gambit that Morphy won in 21 moves, appears in both and I'm close to having it in my long-term memory. I have not yet started the effort to memorize Karpov,A.--Unzicker,W., Nice 1974, which is another suggestion of Engqvist's.

One position that I studied in early January led me to improve my move order in a position that I frequently reach while playing against the Caro-Kann.

Several endgame positions that I played against Stockfish before or after reading Engqvist's notes drove me to dig into some of the volumes in Yuri Averbakh's eight-volume series.

Engqvist's analysis is fresh, lucid, and thought-provoking. Many of his memorable phrases guide me when they should--appropriate moments during play. For example, "Nimzowitsch tried to make his opponent tired and careless by doing nothing" (230). In Duras -- Nimzowitsch, San Sebastian 1912, more than twenty moves of rooks and kings were played in a completely equal endgame. Only when Duras erred did Nimzowitsch move a pawn.

I reflected on this lesson while playing online a completely drawn ending of bishop and knight versus bishop, and then nine moves prior to a draw by the 50-move rule, my opponent allowed a small combination that allowed me to win his bishop. That game, then, became my first opportunity to checkmate with bishop and knight that did not result from a deliberate underpromotion. Because of Engqvist's choice of positions, I had recently practiced that checkmate, too (see "Recognizing Known Positions").

300 Most Important Chess Positions was on my shelf nearly six years, serving as occasional study material and reference for finding positions suitable for some of my students. Now that I've been through every position, I will use it more actively.

I have a to do list that developed as I was going through the book. The list includes studying Jose Capablanca's analysis of a couple of his games in My Chess Career (1920), the only Capablanca authored book that I did not wholly read in 2021. Engqvist brought to my attention a game that Richard Reti analyzes in Master of the Chessboard (1930), which I intend to study. Some of Engqvist's analysis draws from Victor Bologan, Victor Bologan: Selected Games 1985-2004 (2007), and I added it to my library. The long rook endgames and queen endings are games worth reviewing periodically until I absorb their lessons.

Another task presented to me after racing through this book is that Engqvist has also published 300 Most Important Tactical Chess Positions (2020), 300 Most Important Chess Exercises (2022), and Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach (2023). Any or all of these books would be worth my time. Perhaps I'll continue to ignore Engqvist's advice on pacing, and race through his tactics book in the near future.

.jpg)

.jpg)