A couple of days ago, I watched the video, "

Fear the Bishops: Hammer vs. Krasenkow," by Jon Ludvig Hammer on

Chess.com. In this recent video, Hammer shows a game that he played in the sixth round of the 45th Rilton Cup in Stockholm. After five rounds, Michel Krasenkow led the Rilton Cup with 5.0, while Hammer was half a point behind. Hammer had Black and won a beautifully instructive game. That put him in first place, but he fell to second by the end of the event. Maxim Rodshtein

won the event with 8/9 and Hammer settled for second with 7.5.

Even though he was disappointed with his second place finish, Hammer achieved his

2705 rating peak as a result of the event. He was also justifiably proud of his performance in the game against Krasenkow.

After watching the video, I played through the game on

Chessgames.com, then found it among the databases on my computer. After twice through the game on screens, I pulled

Chess Informant 127 from the shelf and went through the game again on the dining room table.

Magnus Carlsen's tweet to which Hammer responded in the tweets visible above highlighted the power of the bishop pair. That theme was also emphasized in Hammer's instructive video of this game. Certainly the game offers great study material for the battle to activate two bishops, turning this imbalance in one's favor. But there is much more in this game. The layers of instruction in the opening, middlegame, and endgame require time to unpack. This game merits extensive study.

Opening

Krasenkow,M (2610) -- Hammer,J (2695) [D38]

45th Rilton Cup 2015–16 Stockholm SWE (6.1), 02.01.2016

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 d5 4.Nc3 Bb4 5.Bg5 h6 6.Bxf6

Magnus Carlsen tweeted, perhaps in jest, that 6.Bxf6 was the losing move.

6...Qxf6 7.Qa4+ Nc6

White to move

In his video, Hammer described the placement of Black's knight on c6 as somewhat awkward. However, this placement is the characteristic feature of the Ragozin System. In

The Ragozin Complex: A Guide for White and Black (2011), Vladimir Barsky notes how views have changed concerning the merits of the placement of this knight.

[T]his queen check, forcing the opponent to play Nc6 and in the process to obstruct his pawn on c7, was for a long time considered to be the demonstration of the incorrectness of the entire Black set-up. Later, thanks to the efforts primarily of Viacheslav Ragozin, it was established that this plan is not so terrible for Black; no sort of blitzkreig is about to happen, and the queen often proves to be unstably placed on a4.

Barsky, Ragozin Complex, 29.

8.e3

The 5.Bg5 line is treated in chapter six of Barsky, but the first reference game there lacks 7.Qa4+, instead having 7.e3. Initially, glancing through this book, I thought that Krasenkow -- Hammer had deviated from the lines discussed in the book.

Nonetheless, Barsky's book does an excellent job of presenting general ideas. Even in positions that deviate from those in the book, an astute reader of

The Ragozin Complex will find guidance understanding this game. The front of the book includes a long essay from the mid-twentieth century: Isaak Lipnitsky, "How to Study a Concrete Opening", originally published as part of

Questions of Modern Chess Theory (1956). Lipnitsky lists three positional themes that guide Black's play:

1) the e6-e5 pawn thrust

2) a light-square strategy

3) attack with the queenside pawn majority

Hammer's "awkward" knight supports the e5 thrust, and indeed, Hammer played this move in the middlegame, sacrificing the pawn when he did. There are also elements of the light-square strategy at work in Black's tactical brilliance later in the game.

8...0–0 9.Rc1

Hammer played 9.Be2 when he had the White pieces in 2013. That game continued 9...Bd7 10.Rc1 Qe7 11.Qc2 dxc4 12.Bxc4 e5 13.0–0 exd4 14.Nd5 Qd6 and Black won in 49 moves, Hammer,J (2629) -- Tari,A (2293), Fagernes 2013.

Instead of 10.Rc1 as Hammer played in 2013, a later game continued 10.Qb3 dxc4 11.Qxc4 Qe7 12.a3 Bd6 13.Nd2 Nb8 14.Bf3 Bc6 and was drawn in 101 moves, Eljanov,P (2723) -- Wojtaszek,R (2733), Biel 2015.

9...Qg6

White to move

The move order makes it easy to overlook Barsky's analysis of this position in chapter one, which highlights games featuring 5.Qa4+. Michal Krasenkow is mentioned as one of the strong players who has favored the 5.Qa4+ approach against the Ragozin. The position in Hammer's game after 9...Qg6 is presented in an analysis diagram in

The Ragozin Complex (65).

10.Qc2 Qxc2

Barsky writes, "Black could keep queens on the board, at the cost of exchanging bishop for knight, but then White would be fine in the middlegame" (65). So, ten moves into the game, already it is Black who is playing for a win!

11.Rxc2 Rd8 12.a3 Bf8

When does a transition from opening to middlegame take place? The rules are not so clear as to be easily applied in all cases. For Barsky, this game has now reached an endgame.

White has a little more space and it is easier for him to complete his development. Black has two bishops and a sound pawn structure. In this complicated endgame, reached after just 12 moves, White has a slight initiative, but it is not so hard to neutralise.

Barsky, The Ragozin Complex, 66.

Middlegame

White to move

13.Be2 Na5N

In the analysis game presented by Barsky with 13.Be2, 13...a6 was played. His main line here continues 13.Nb5, a move suggested two moves later by Tomislav Paunovic in his annotations on this game for

Chess Informant 127/148.

Another game continued 13...Ne7 14.0–0 c6 15.b4 dxc4 16.Bxc4 Nd5 17.Nxd5 exd5 18.Bd3 a5 19.Rb1 axb4 20.axb4 Ra3 Radjabov,T (2713) -- Aronian,L (2803), Beijing 2013. Black won in 76 moves.

Hammer's novelty, as he explains in the video, was intended to provoke White to make a decision concerning his c-pawn.

14.c5 Nc6 15.b4

15.Nb5!?

Informant 127/148 with a line given that ends as unclear. In this line, Black's rook temporarily moves to an awkward square as in Barsky's line after 13.Nb5.

15...g5

How often does a player who has castled thrust the pawns in front of his king forward against an uncastled king?

16.g4

Of course, White does not want to leave his king in the center, so Black's pawn storm must be stopped.

16...e5

The thematic push in the Ragozin. However, here, Hammer sacrifices a pawn.

17.Nxe5

17.Nb5!? is suggested in

Informant.

17...Nxe5 18.dxe5 a5!

White to move

In the middlegame, players maneuver their forces, probing for targets and aiming to produce weaknesses that might be exploited in the endgame. Part of what drove me to spend more time studying this game was my observation of unusually poor ability to predict Hammer's moves through the course of the middlegame.

19.0–0

Now that White has castled, perhaps the opening phase has ended.

19...axb4 20.axb4 c6 21.Rd1 Bg7 22.f4 Re8

A line given in

Informant leads to a position quite similar to one reached in the game: 22...gxf4 23.exf4 f6 24.exf6 Bxf6 and Black has compensation for the sacrificed pawn, according to Paunovic.

23.Kf2

Black to move

23...gxf4

Hammer spends a bit of time explaining why it was necessary to prevent White playing e4. One line that he offers is 23...f6 24.e4 dxe4 25.f5 fxe5 26.Nxe4. Black's bishop pair confers no advantage here.

24.exf4 f6 25.exf6 Bxf6 26.h3 Ra3

With this move, Hammer begins his plan to exploit weaknesses on the queenside, both pushing his passed d-pawn (part of a queenside majority) and demonstrating that the light squares a2, b3, and c4 are critically important. It is a pretty fair bet that he has spent some time studying Lipnitsky's essay.

27.Rd3 Kg7 28.Kf3 Be6 29.Nd1 Ra4 30.Rb3

Black to move

30...d4

White must be aware of a checkmate threat using a crisscross pattern of the two bishops. In the video, Hammer shows this possibility as his motivation for playing 30...d4. That's an important lesson for most of the audience that consumes

Chess.com videos. On the other hand, Grandmasters do not habitually play moves because there is a remote possibility of checkmate if the other player blunders. There must be a strategic or tactical point beyond hope chess.

Here, Black is pursuing the light-square strategy mentioned by Lipnitsky.

So as to turn these weakened squares into an "incurable weakness", Black tries to exchange off the enemy light-squared bishop, i.e. the very piece which is best suited to the defense of these weakened light squares.

Lipnitsky, "How to Study a Concrete Opening," in The Ragozin Complex, 24.

Both the means of weakening the light-squares on the queenside and the particular squares in focus differ a little between this game and those in Lipnitsky's examples. That difference is evidence of the imagination that Hammer credited to himself for this victory.

31.Bc4 Ra2!

Every commentator has mentioned this move. Yesterday, I let FM Jim Maki look at my copy of

Informant 127, telling him that I have been studying this game. He provides game analysis at most of Spokane's youth tournaments. While I was getting round one started, Maki had a few minutes before the youth players would arrive at his table. When I returned to his table between rounds one and two, he mentioned this move.

32.Rxa2 Bxc4 33.g5

Hammer notes that after 33.Rba3, 33...Bxa2 would be premature. His bishop pair have such strength that he would prefer to remain down the exchange.

33...Bxb3 34.gxf6+ Kxf6 35.Rd2

Ending

Black to move

When you have a bishop against a knight, it is usually your choice when to exchange minor pieces, according to Hammer.

35...Bxd1+ 36.Rxd1

Black to move

Hammer's demonstration that this rook ending is winning for Black begins with a tactical maneuver that renders White's king a passive defender.

36...Re3+ 37.Kf2 Re4 38.Rd3

38.Kg3 Kf5

38.Rg1 Rxf4+ 39.Ke2 Rh4

38...Rxf4+ 39.Ke2 Ke5 40.Rg3 Ke4 41.Rg7 d3+ 42.Kd2 Rf2+ 43.Kc3 Rc2+ 44.Kb3 Rc1

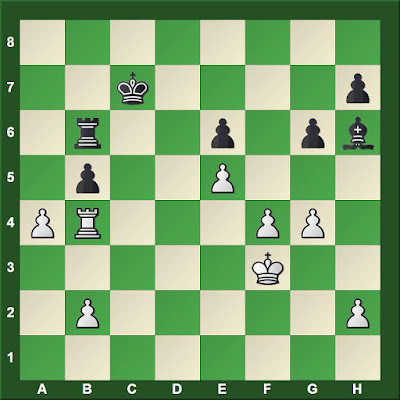

White to move

45.Re7+

Hammer explains why the b-pawn is safe, for example 45.Rxb7 d2 46.Re7+ Kd3 47.Rd7+ Ke2 48.Re7+ Kf1 49.Rf7+ Kg2

45...Kf3 46.Rf7+ Ke2 47.Re7+ Kd1 48.Kb2 d2 49.Re4

Black to move

49...Rc2+

When I showed this diagram to some youth students on Thursday, one of them suggested 49...Ra1. Together, we demonstrated that 50.Kxa1 leads to an easily won pawn ending for Black, whose h-pawn will promote. Of course, nothing compels White to capture the rook, but then it can move to a3 and threaten the pawn on h3. My student's plan is winning, but Hammer's play is more precise.

50.Kb1 Rc3 0–1