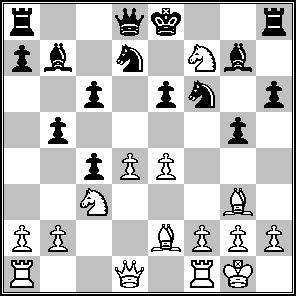

In the

World Chess Championship taking place in Bonn, Germany right now, Viswanathan Anand is one win or two draws from match victory. If Kramnik manages four consecutive wins in all the remaining scheduled standard time games, on the other hand, he will regain the champion’s title. If Kramnik wins three and draws one, the players will play rapid games as tiebreaks. Kramnik’s chances look bleak. It even appears unlikely at this point that there will be a twelfth game.

In the past, there have been several astounding comebacks in World Chess Championship matches.

Steinitz – Zukertort 1886

In the first “official” WCC match, Wilhelm Steinitz won the first game. Then Johannes Zukertort won four in a row. After five games, Steinitz was down by three. Steinitz won the next two games, followed by a draw. In game nine, Steinitz tied the match. By game twelve of the match the first official World Chess Champion had a two game lead. Steinitz won 12½ - 7½.

Through several subsequent matches, Steinitz was not down by more than one game until his 1896 match with Emanuel Lasker. Lasker won the first four games, and was ahead 9-2 (four draws) before Steinitz won game twelve. Lasker won the match 12½ - 4½.

Euwe – Alekhine 1935

Alexander Alekhine failed to defend his world title against Max Euwe. But in this thirty game match, Euwe came back from a brief three game deficit to tie the match. Then Euwe pulled ahead. Alekhine won the first game; Euwe won game two. Then Alekhine won two, followed by two draws, and another Alekhine win. After seven games, Euwe was down 5-2. However, as the players had agreed to play a long match, Euwe had plenty of time to recover. The next three games were decisive—Euwe won, then Alekhine, then Euwe.

After twenty-four games, the score was 12-12 with ten draws and seven wins each. Euwe won games twenty-five and twenty-six, and then Alekhine won one. The event finished with three draws, although Euwe had a superior position in the final game. Euwe won 15½ - 14½ .

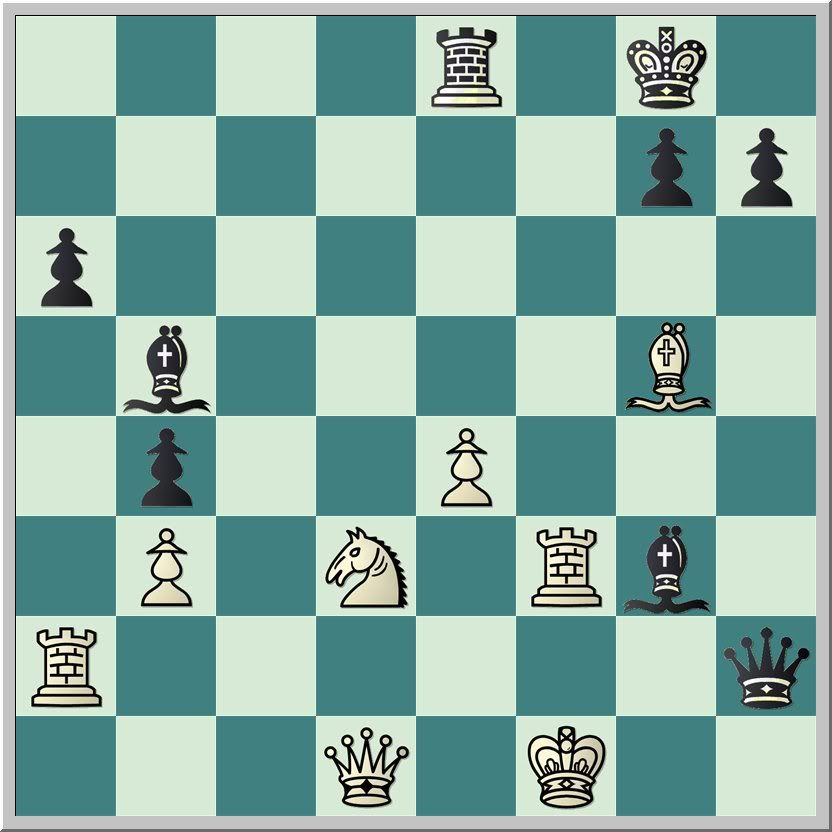

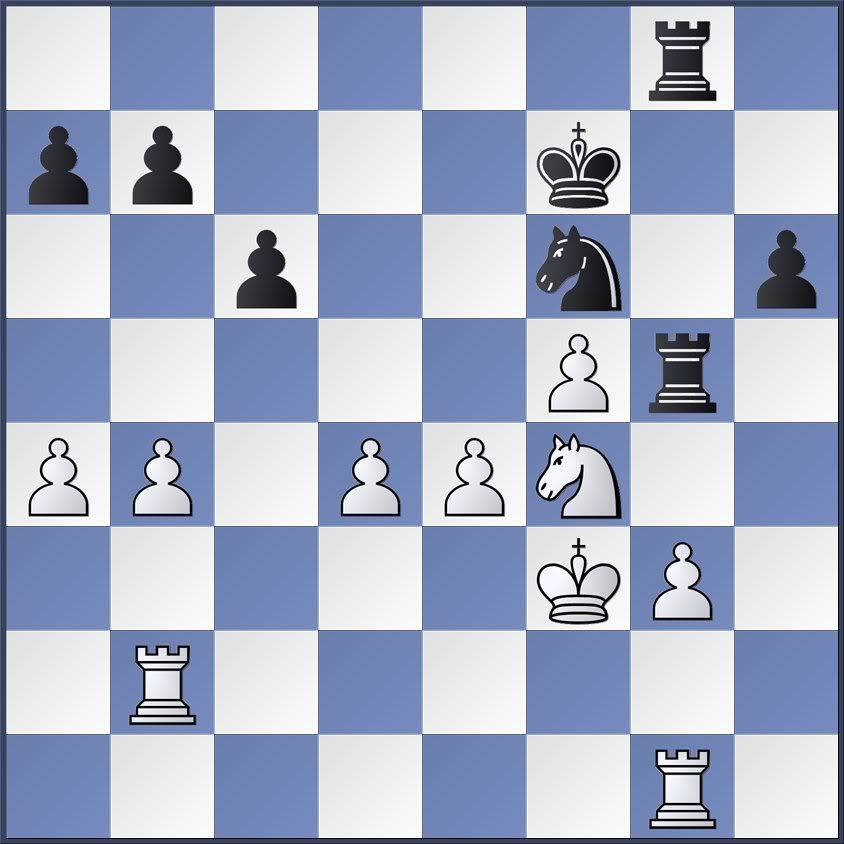

White just played Rf1-g1 and the players agreed to a draw.

In the rematch two years later, Euwe had a one game lead after five games and a three game deficit after ten. Alekhine regained his title 15½ - 9½ . He then held the title until his death in 1946. There were no WCC matches during the Second World War.

Fischer – Spassky 1972

In Reykjavik, Bobby Fischer lost the first game, and then forfeited game two due to his unresolved complaints about noise and lighting. From this two loss deficit, Fischer stormed back, winning games three, five, six, eight, and ten. Spassky could not recover from his three game deficit. Fischer won 12½ - 8½.

Among the demands Fischer put forth as conditions for World Chess Championships was his insistence that a match should continue until one player had won six games. FIDE could not accede to this demand, which is a nightmare for organizers.

Kasparov – Karpov 1984

After winning the title by default, Anatoli Karpov won more tournaments than any previous world champion. He also twice successfully defended his title against Victor Korchnoi, 1978 and 1981. In 1984 a match was arranged with the young new challenger, Garry Kasparov, and with the conditions Fischer had sought. Draws would not count in the result. To gain or retain the WCC title, a player had to win six games.

The first decisive game was the third of the match. Karpov won that game, then won six, seven, and nine. The next seventeen games were drawn, but then Karpov achieved his fifth win. Kasparov began a comeback with a win in game thirty-two. A string of fourteen more draws was capped by two successive Kasparov wins. With Karpov leading 5-3 and forty draws, the match was suspended. It had been running from September 1984 to February 1985.

A new match began in September 1985. In this resumption, the old system of best of twenty-four games was in place. Kasparov won the first game, lost games four and five, and then won game eleven. He won this match 13 – 11.

Perhaps this pair of matches should be regarded as the greatest comeback in World Chess Championship history. After seventy-two games, each player had eight wins and fifty-six draws.

In 1986, Kasparov was never behind in the match against Karpov. However, in 1987, each player won four games, Karpov winning first in game two. Kasparov retained the title due to the 12-12 tie. In 1990 Kasparov won the fifth WCC match between these two men 12½ - 11½.

Kasparov surrendered his WCC title to Vladimir Kramnik in a match scheduled for sixteen games in 2000. Kramnik won games two and ten; the rest were draws. After fifteen games, he achieved the 8½ needed for victory. Kramnik won 8½ to 6½.

Leko – Kramnik 2004

In Kramnik’s first title defense, the players agreed to play best of fourteen games with the reigning champion getting draw odds. Kramnik won the first game, but Peter Leko won games five and eight. Going into game fourteen, Kramnik needed a win with Black to tie the match and retain the title. He succeeded.

Topalov – Kramnik 2006

In Kramnik’s next title defense, he was considered the challenger by FIDE. This match was to unify the title that had split in 1993 when Kasparov organized a WCC title defense outside the auspices of FIDE. Kramnik won the first two games, then the psychological war began. Restrictions on use of the loo led to Kramnik forfeiting game five. Topalov won games eight and nine. Depending on one’s interpretation of Kramnik’s appeal, he was either one game down or even with Topalov when game ten began. Kramnik won this game. After two more draws, the twelve game match concluded without result. Lack of clarity regarding the identity of challenger and champion precluded any possibility of the champion having draw odds, so the players began a four game rapid match. Kramnik won two and lost one. Depending on how the split is viewed, Kramnik either retained the title or became the World Chess Champion by a score of 8½ - 7 ½. The open dispute regarding game five was rendered moot.

Three times, new World Chess Champions have been crowned after having been down three games in a match—Steinitz, Euwe, and Kasparov. In none of these has the future champion been down three games with four remaining.