Paata Gaprindashvili, Imagination in Chess: How to Think Creatively and Avoid Foolish Mistakes (2004) has been on my shelf for more than a decade. I have read and reread it, and have often found myself repeating its advice to my students.

Gaprindashvili writes, "If we fail to make an idea work, we need to stop and ascertain the cause of the failure (i.e. answer the question 'why?'), and then attempt to correct our design" (40). This sentence, which I have paraphrased to my students on numerous occasions, forms the heart of what the author calls "reciprocal thinking," the title of the second chapter. Imagination in Chess is devoted to "the evaluation and development of the brain's reflective activity" (5).

The book contains a minimum of prose. The only chess books on my shelves with less text are those published in the language-less format of Chess Informant. Even so, the prose is focused and well integrated with the 756 exercises. Gaprindashvili urges his readers to read the first section of instruction, solve a few problems, read the next section, and so on. After passing through the book in this manner, the reader should go back through the book again, and again. With enough time spent repeatedly passing through Imagination in Chess, the thinking process will become second nature. Hopefully, "regular solving of the exercises will improve the cogitative action of the brain and raise your standard of play" (5).

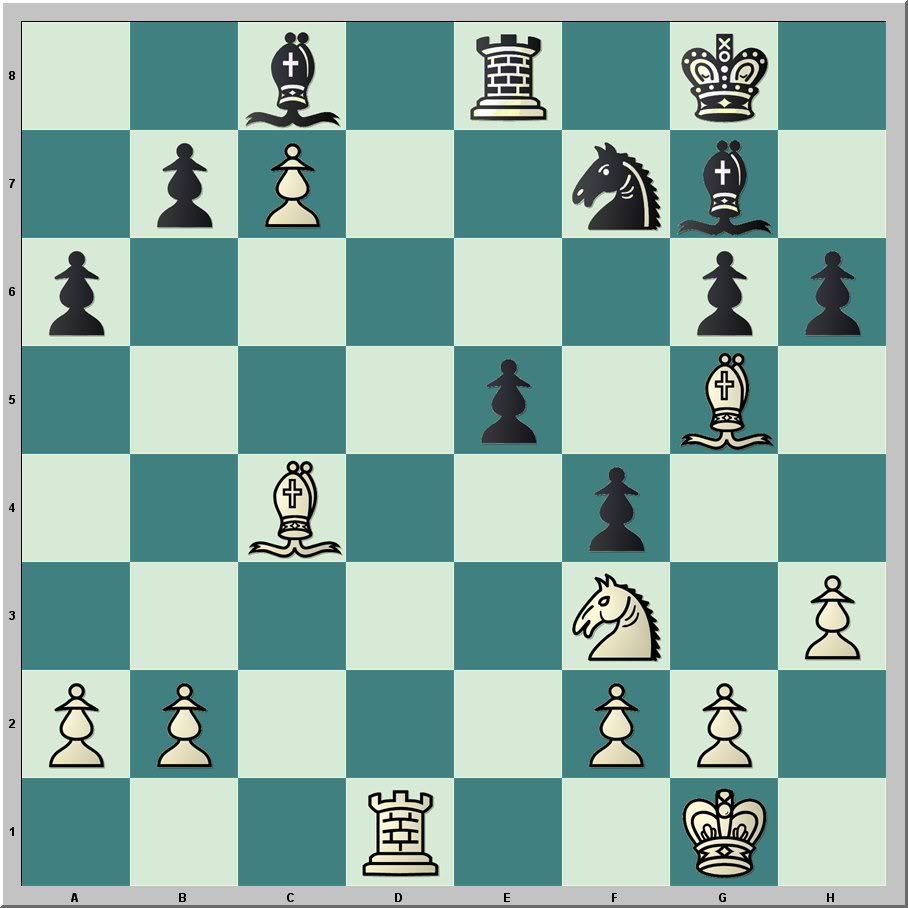

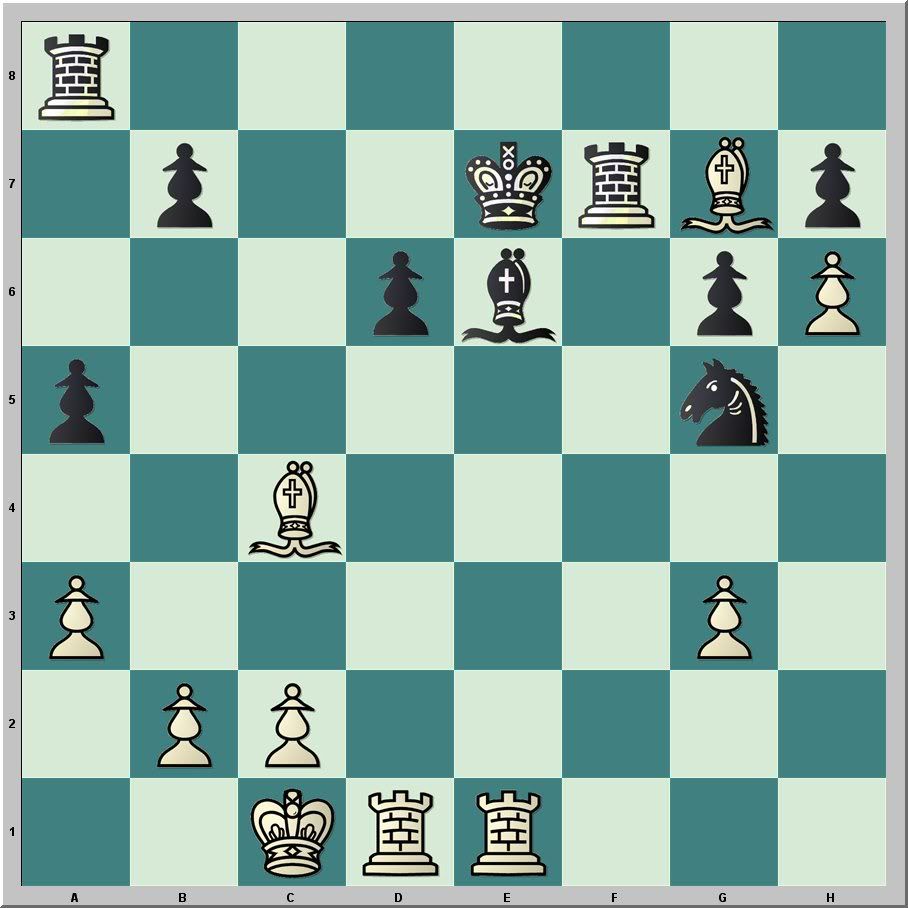

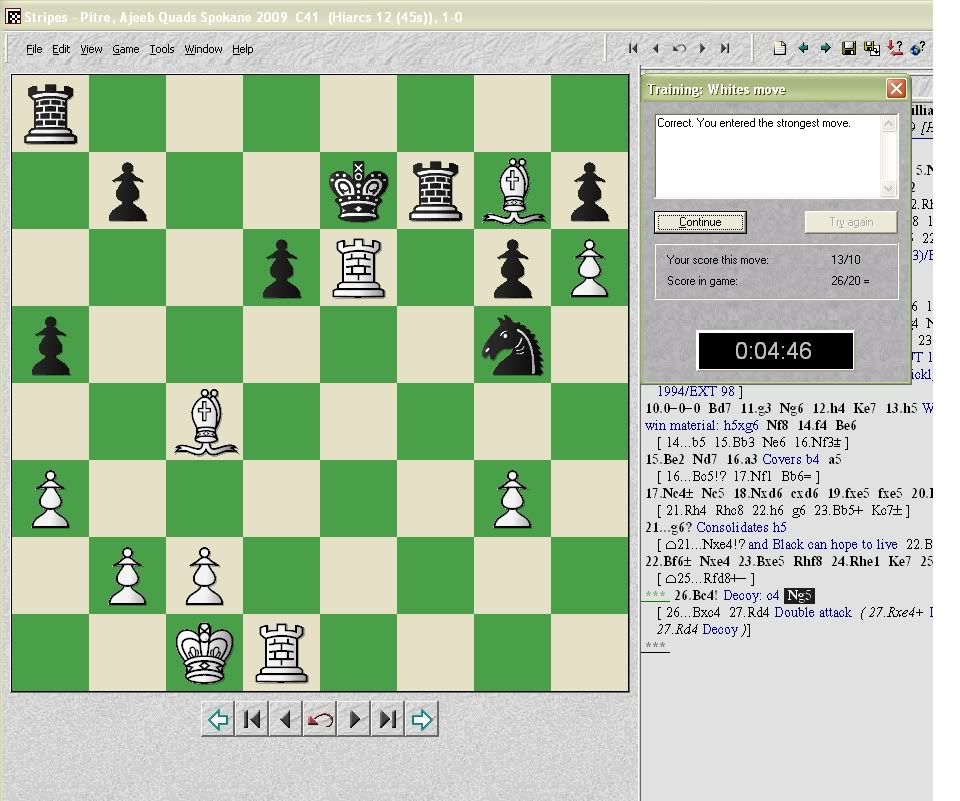

The book contains seven chapters of decreasing length. The instructive portion is well illustrated with flow charts (see image below).

The thinking process advocated appears to be a refinement of Alexander Kotov's well-known "tree of analysis" in Think Like a Grandmaster (1971). It is refined in both its simplicity and flexibility. Gaprindashvili's first step is to study the position. "[I]dentify all of the tactical and strategic peculiarities" of the position (7). This process will reveal certain ideas from which will flow candidate moves. A student employing Kotov's process will then examine each candidate move in turn, analyze each candidate move for the opponent for each of these candidates, and so on. In Gaprindashvili's system, if calculation of the variations following from the first candidate move leads to a positive verdict, you play it. Kotov would hesitate until all candidates had been examined.

The chess positions comprise the bulk of the book. Although varying considerably in difficulty, these are generally quite challenging even to very strong players. They are also fresh. Most of the positions are not found in other books. Even readers who choose to ignore Gaprindashvili's system of progressive thinking, reciprocal thinking, mental agility, and imagination will benefit from study of the positions.

There have been criticisms of this book by those who take the time to check solutions via computer. For example, Sam Copeland explained in a comment to his "25 Books Guaranteed to Improve Your Chess" on Chess.com (12 January 2015) why he excluded this book. The book had been mentioned in a comment by Matty D. Perrine, who asserted it was the "best tactic book" he had gone through. Copeland said that he wanted to like Imagination in Chess, but found some of the solutions frustrating. He offers two examples from the first ten in the book. The diagram below is the book's sixth position.

White to move

Copeland may be correct that his solution is stronger than the one given in the book (my computer favors his at a depth of 34 ply), but the solution given was the one played in the game. The move played also reinforces the thinking process outlined in the first chapter.

Gaprindashvili's solution is historically accurate, but perhaps not the strongest move. The play after Copeland's move seems a little more straightforward. Some readers might prefer that alternate solutions to those played should be given in the book, especially when they are as strong or stronger.

While Copeland's criticism has some merit, I would recommend this book to my readers except for one small problem. the book is out of print. Consequently, new copies, when they can be found, are quite expensive. Amazon lists several third party sellers with the book for $118 plus shipping. Used copies start at $55. When I bought the book, it sold for $22.95.