The Berlin Defense (ECO C65-C67) in the Spanish Opening (or Ruy Lopez) is a major alternative to the more common Morphy Defense. It was popular in the nineteenth century, but passed out of favor in the early twentieth. Fifty years ago, the Berlin was described as "fundamentally too passive" (Leonard Barden,

The Ruy Lopez [1963], 145). Even so, the opening had adherents, such as GM Arthur Bisguier.

Vladimir Kramnik's use of the Berlin Defense in his World Championship match with Garry Kasparov revived the opening. It has retaken its position as an important opening played regularly in top tournaments. It appeared in four of the ten games in the 2013 World Championship. Magnus Carlsen employed it three times, and Viswanathan Anand played it once. Although the opening has a reputation for being drawish, it often creates imbalances that allow either side to play for an advantage long into the endgame. Carlsen scored

one of his victories in the match when Anand faltered in a long and difficult endgame that began with the Berlin Defense.

The opening's name stems from it having been recommended in

Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin 1843), edited by Tassilo von Heydebrand und der Lasa and Paul Rudolph von Bilguer. Bilguer began the project, but died before bringing it to publication. Lasa completed the project and continued updating it through four more editions (1852, 1858, 1864, 1874). The so-called Morphy Defense (3...a6) does not appear in the first edition of the

Handbuch, but is treated in the 1852 edition, where Lasa asserts the superiority of 3...Nf6.

Dieser Zug, welchen der Anonimo Modenese angiebt, kann sehr gut geschehen. Hätte Weiss aber die Absicht, sogleich Sc6 zu nehmen, so würde Schwarz durch 3.Sg8 nach f6 statt a7-a6 dann wegen des Angriffs auf e4 noch etwas besser entwickelt sein.

Tassilo von der Lasa, Handbuch (1852), 162.*

The Ruy Lopez opening received its name from the

Handbuch des Schachspiels using the term, "The Knight's Game of Ruy Lopez," according to Howard Staunton (

The Chess-Player's Handbook [1847], 147).

The Berlin Defense was considered a standard response to the Spanish in 1889 when Wilhelm Steinitz advocated the system (3...d6) that would come to bear his name (Steinitz,

The Modern Chess Instructor [1889], 1). There, the Morphy Defense (3...a6) was considered an alternate main line. Johann Jacob Lowenthal, however, asserted two decades earlier that Morphy's move is "generally considered best" (

The Chess Player's Magazine, vol. 1, New Series [1865], 45). According to Lowenthal, Domenico Ercole del Rio had first suggested the move that became associated with Morphy following his match with Adolf Anderssen.

Lowenthal's assessment differs from that of Max Lange a mere five years earlier. Lange wrote in

Paul Morphy: A Sketch from the Chess World, trans. Ernest Falkbeer (1860) that 3...Nf6 "would be stronger" than Morphy's 3...a6, as played in games two and four of his match with Anderssen. White's bishop is "well placed" at a4 and "if Black, in order to dislodge him, should venture upon advancing the [b-pawn], the queen's side will be exposed" (256). Lange refers his readers to "elaborate analysis" in

Sammlung neuer Schachpartien (1857).

There Lange offers the history that Ruy Lopez de Segura recommends 3.Bb5 against the knight's defense of the pawn on e5, which the clergyman considered better protected by the pawn move 2...d6. Lange explains that the opening is called the Spanish Game or Ruy Lopez due to this analysis offered by the priest in 1561. His reasoning does not match the Spanish master's, he notes. Rather, he asserts that Black's efforts to drive away the bishop allow it to take up residence on b3 with no loss of time, while also weakening Black's queenside. However, the recommendation of the Berlin School offers Black compensation (43-44).

Die allgemeine Theorie ist aber spater jenem Rathe des spanischen Meisters nicht vollkommen beigetreten; sie hat vielmehr nach Aufrechterhaltung der Vertheidigung 2. Sb8 — c6 nun bei 3. Lfl — b5 durch die von der Berliner Schule vorgeschlagene Entgegnung 3. Sg8 — f6 die Spiele schnell auszugleichen empfohlen.

Lange, Sammlung neuer Schachpartien (1857), 43

The importance of the Spanish Opening is revealed, Lange asserts, in the attention it receives from Tassilo von der Lasa, Carl Friedrich Jaenisch, and Howard Staunton.

Lasker's Advocacy

Truth derives its strength not so much from itself as from the brilliant contrast it makes with what is only apparently true.

Emanuel Lasker, Common Sense in Chess (1917), 25

The Morphy Defense first surpassed the Berlin system in popularity, according to the ChessBase database, in the 1870s.** However, they remained close to equal through the 1880s and 1890s, and then in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Morphy variation was played three times as often as the Berlin. In the next decade, 3...a6 appeared five times as often as 3...Nf6.

The Berlin Defense to the Spanish Opening had reached it peak of popularity, while the Morphy Defense dramatically increased its adherents at the same time that Emanuel Lasker presented his lectures that would be published as

Common Sense in Chess. The lectures were presented in spring 1895 and the first edition of the book appeared in 1896. After several editions by several publishers, a corrected edition was published by David McKay in 1917. That edition was reprinted as a cheap Dover paperback in 1965 that remains widely available today.

Lasker's central purpose in the lectures and book were to lay out general principles for all phases of the game. His opening principles are put forth in "

Lasker's Rules". These conclude the first lecture. In the second lecture, he offered two games and variations that illustrate these rules at work in the Spanish Opening. In the third lecture, he offered some discussion of the Morphy Defense, which he notes at the outset violates one of his opening principles. The Berlin Defense conforms to Lasker's rules.

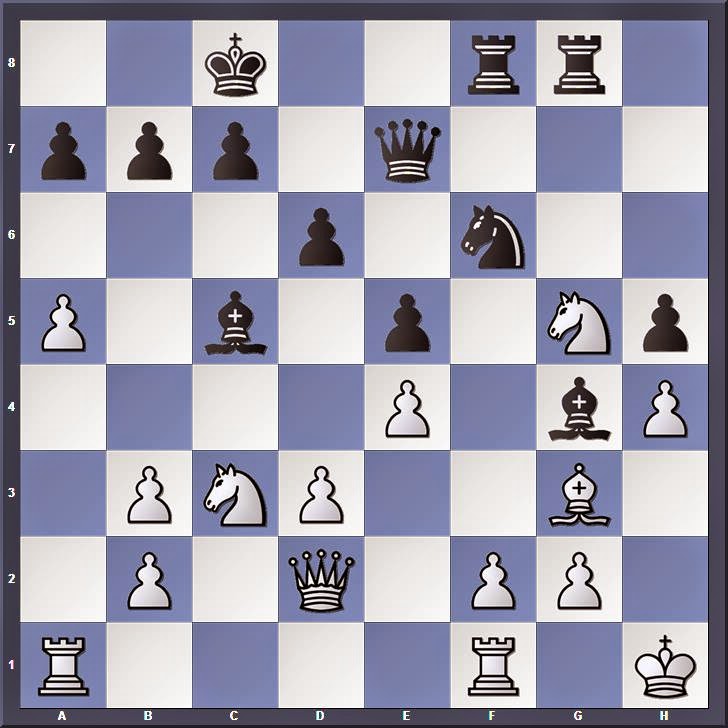

In his first illustrative game in the second lecture, we have the moves

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6 4.O-O Nxe4 5.Re1 Nd6

White to move

Lasker observes of 5.Re1, "[n]ot the best move, but one that most naturally suggests itself" (19). Nonetheless, Carlsen played this very move in

game 8 of his match with Anand. That game followed a line that had been employed in the first official match for the World Championship in 1886, deviating only with 12...Ne8.

Lasker's continuation from the diagram has been rare (24 games in ChessBase Online).

6.Nc3

6.Nxe5 is the overwhelmingly most popular choice, followed by 6.Bxc6 in roughly one-quarter of the games.

6...Nxb5 7.Nxe5

"Cunning play." Lasker observes, "If Black now takes one of the knights he loses" (19).

Lasker presents some lines after 7...Nxc3 in which White either gains a piece or generates a mating attack against the king. These seem useful instruction for developing players. In his main line, after 7...Be7, Black ends up with a better game.

And Black's game is, if anything, preferable. You see how quickly White's attack has spent itself out. But then he did not make the best of his position at move 5.

Lasker, Common Sense, 21

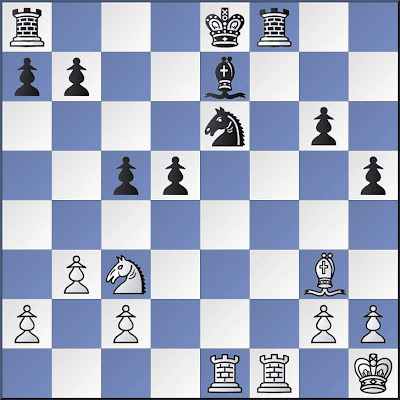

Lasker returns to the main line after 4.O-O Nxe4, offering what remains today White's most popular move.

5.d4

Black to move

Here, 5...Nd6 has become Black's most popular response. Lasker continued with 5...Be7, the second most popular move today.

6.Qe2 Nd6 7.Bxc6 bxc6 8.dxe5 Nb7

After 5...Be7, the rest of Lasker's moves remain the top choices in this line.

White to move

Lasker's comments on the diagram ring true today:

We have no come to a critical stage. Black's pieces have retired into safety, ready, with one single move, to occupy points of importance. White, on the contrary, has the field to himself, but he can do nothing for the present, as there is no tangible object of attack. Various attempts have been made to show that White has here the superior position. I do not believe that White has any advantage, and am rather inclined to attribute the greater vitality to the party that has kept its forces a little back. (23)

The Berlin Defense offers several prospects for interesting and dynamic play. It can produce a tactical melee, a positional squeeze, or a cold and lifeless position that leads to an early draw. I was happy to see several variations of this old and new opening system deployed in the recently completed World Championship match.

*I received

assistance translating this passage from a member of

Chess.com, hauntedgarage2000. He offered: "This move, described by Anonimo Robenese, could possibly occur. But if White would take Nc6 immediately, Black then will be a bit better developed with 3. Ng8 to f6 instead a7 to a6 because of his threat towards e4." Another member of the site, Kevin Hermann, helped by translating a passage from the 1843 text.

Corrections to my transcription to this passage were made 27 November 2013. Thanks to additional help from McHeath on

Chess.com for pointing out four spelling errors. In addition, Anonimo Robenese should be Anonimo Modenese, a name associated with Domenico Ercole del Rio (see also "

Morphy Defense: Early History").

**The more time that I spend reading nineteenth century chess books and periodicals, the more I realize that ChessBase and other electronic databases are woefully incomplete as historical references. Aside from the most highly publicized matches and tournaments, and the records of the best known players, the games in nineteenth century publications are mostly absent from databases.