A Strategic Masterpiece

As one of the most important games from one of the strongest tournaments ever held, it makes sense that Botvinnik -- Capablanca, AVRO 1938 should be highly regarded. The game is deceptively simple, which leads some critics to dismiss it as not worthy of consideration as one of the greatest games ever played. However, it is historically significant--a watershed event in the development of professional chess. It is also a rich strategic masterpiece. Early in the game, both players adopted clear plans that were clear to their opponent. Mikhail Botvinnik's plans succeeded, while Jose R. Capablanca's plans proved too slow.

What accounts for the difference? Surely, Botvinnik did not calculate to the end to realize that his plans were superior. Was his success the result of home preparation? An interesting statement by an unsigned annotator appears at the end of the game in the ChessBase PowerBook database:

Capablanca's resignation, in my opinion, symbolized the end of an heroic era of chess titans, dominating the field with their natural genius. Since this historic moment the professional touch has played a more and more important role as an integral part of chess, the path to ultimate success.

ChessBase PowerBook*

This game is one of two that received a perfect score from the editors of

The World's Greatest Chess Games (1998)--Graham Burgess, John Nunn, and John Emms. That was sufficient for me to include it on my list of ten candidates for the "

Best Chess Game Ever Played." After last week's Spring Break Chess Camp, I decided to spend more time with these ten games.

Over the past several days, I have repeatedly gone through this game on my iPad and with select students. On Sunday, I sat at the table in front of a chess board and played through the game with Botvinnik's annotations in

One Hundred Select Games (1960). Then, I read the annotations in Garry Kasparov,

My Great Predecessors, Part II (2003); and in

The World's Greatest Chess Games. I also watched videos by

Kingscrusher,

Jerry at ChessNetwork, and

A. J. Goldsby.

Botvinnik,Mikhail -- Capablanca,Jose Raul [E49]

AVRO Holland (11), 22.11.1938

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e3

Lots of moves have been tried here, but this remains the most popular. Botvinnik's comment is interesting.

The Nimzo-Indian Defence is not to be refuted in this way, but recent practice has shown that it is doubtful whether there is any refutation.

Bovinnik, One Hundred Select Games, 154.

4...d5

Possibly dubious for reasons made clear in this game.

5.a3

5.Nge2 dxc4 6.a3 Ba5 7.Qa4+ c6 8.Qxc4 0–0 9.Ng3 Nbd7 10.f4 Nb6 11.Qd3 c5 12.dxc5 Qxd3 13.Bxd3 Bxc3+ 14.bxc3 Na4 and drawn in 33 moves. Euwe,M -- Capablanca,J, Amsterdam 1931.

5.Qa4+ Nc6 6.Nf3 0–0 7.Bd2 Bd7 8.Qc2 Re8 9.Rd1 Bd6 10.Bc1 a5 11.a3 a4 12.c5 Bf8 and White won in 57 moves. Eliskases,E -- Ragozin,V, Moscow 1936. One of the games that led to the name and principles of the Ragozin System.

5.Nf3 is the main line 5...0–0 6.Bd3 c5 7.0–0 Nc6 8.a3 Bxc3 9.bxc3 b6 10.a4 cxd4 11.cxd5 Qxd5 12.exd4 Bb7 13.Re1 Rfd8 and drawn in 42 moves, Alekhine,A -- Keres,P, Holland 1938. From the same tournament.

5...Bxc3+

5...Be7 is playable, but Black has given up a tempo to assist White's queenside expansion.

6.bxc3 c5

6...0–0 7.cxd5 exploits the inaccuracy of 4...d5.

6...c6.

7.cxd5 exd5

White has undoubled his pawns, casting doubt on the wisdom of 4...d5.

8.Bd3

8.f3 has become popular.

8.dxc5 was played in the previous game that reached this postion 8...0–0 9.Bd3 Nbd7 10.Ne2 Nxc5 11.Bb1 b6 and Black won in 52 movess, Landau,S -- Keres,P, Zandvoort 1936.

8...0–0 9.Ne2

When I was racing through this game quickly, this was the first move that caught my eye. As I began to understand this game, however, it became clear that this was a vital part of White's overall plan. Botvinnik understood the sort of position in which Philidor's famous advice was apropos. The knight must support and not impede the advance of the e- and f-pawns.

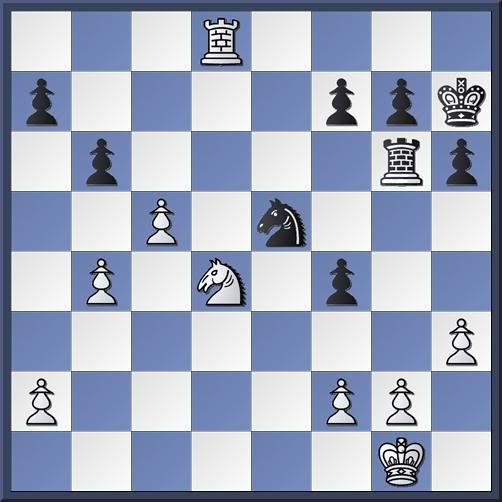

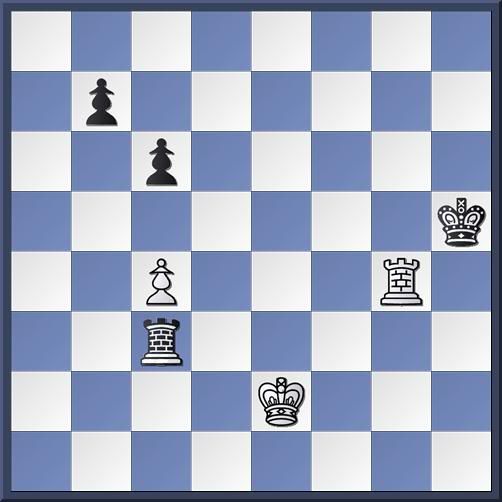

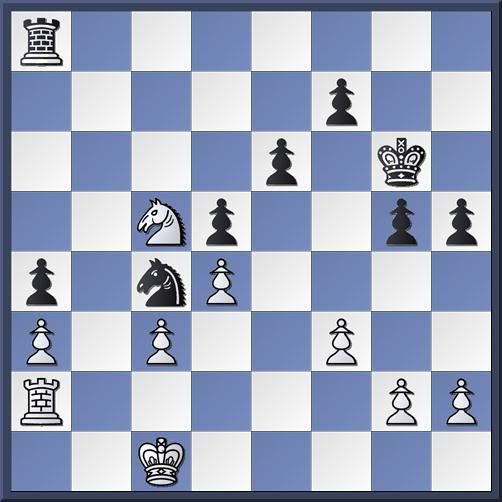

Black to move

Both players have clear middlegame plans rooted in their respective pawn majorities. White will expand in the center and kingside; Black will play on the queenside. In the ensuing battle, White's plan proves to be faster.

9...b6 10.0–0 Ba6 11.Bxa6

Giving up the bishop pair may seem odd, but this move gains a tempo or two.

11.Bc2 Botvinnik suggested that maybe he "should have" retreated the bishop (154), but it is worth noting that doing so did not work out so well for White two years earlier. 11...Nc6 12.Re1 Re8 13.f3 Rc8 14.dxc5 bxc5 15.Ng3 d4 16.exd4 cxd4 17.Rxe8+ Qxe8 18.cxd4 Nxd4 19.Ba4 Qe5 20.Rb1 Nd5 21.Bb2 Nc3 22.Bxc3 Rxc3 23.Kh1 h5 24.Bd7 Rd3 25.Qa4 Bb7 26.Ne4 Bxe4 27.fxe4 Nf3 0–1 Stahlberg,G (2531) -- Keres,P (2567), Bad Nauheim 1936.

11...Nxa6 12.Bb2?!

An inaccuracy, according to Botvinnik.

12.Qd3, provoking Qc8 was better.

12...Qd7!

Capablanca understands the light-squared battle ahead. This move also threatens penetration on the queenside.

13.a4

Necessary to prevent Qa4.

13...Rfe8?

"A surprising mistake for Capablanca to make" (Botvinnik, 155).

13...cxd4 14.cxd4 Rfc8 and Black is slightly better. "White would probably have sufficient resources available for his defence" (Botvinnik).

14.Qd3 c4? 15.Qc2

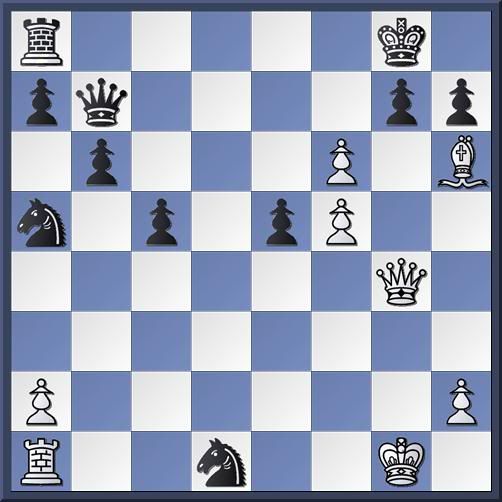

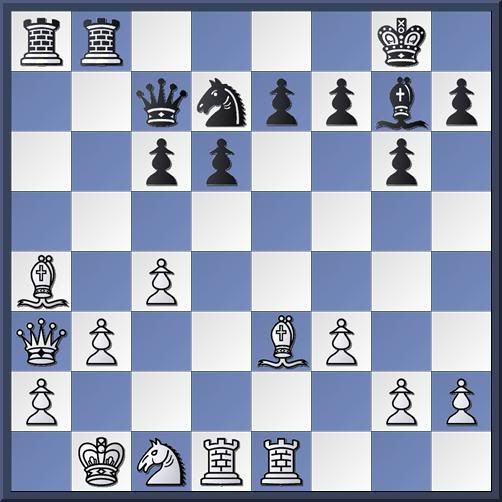

Black to move

|

| Yellow, as in the game; or green (my suggestion)? |

15...Nb8

Knowing how the game concluded makes it easier to find fault with Black's plan.

I like 15...Nc7 with the idea of employing the knight in defense.

16.Rae1! Nc6 17.Ng3 Na5 18.f3 Nb3 19.e4 Qxa4 20.e5 Nd7 21.Qf2

21.f4? produces a useful tactics exercise

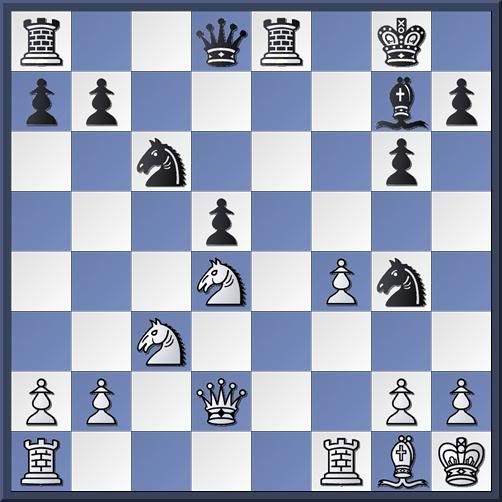

|

| Black to move (analysis diagram) |

21...Nbc5! 22.Qe2 Nd3 23.Rb1.

21...g6 22.f4 f5

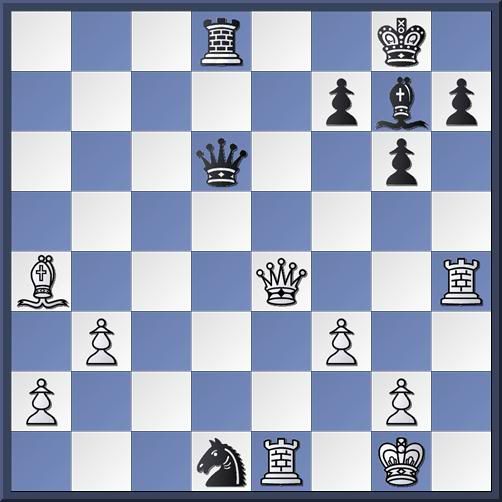

Another exercise from this game. Does the student understand the strategic requirements of the position?

White to move

23.exf6

The only chance for an advantage.

23...Nxf6 24.f5 Rxe1 25.Rxe1 Re8

Yet another useful training position. I played out this position with a student on Monday. His 26.fxg6 presented some challenges at the rapid pace that we played. It does seem inferior to Botvinnik's move, however.

26.Re6! Rxe6 27.fxe6 Kg7 28.Qf4 Qe8 29.Qe5

29.Qc7+ has been suggested by several students, and appears to be as strong as Botvinnik's move in the game. 29...Kg8 30.Qe5 Kg7 31.Ba3.

Black to move

29...Qe7?

Botvinnik stated that this move was "inevitable" (156).

However, 29...h6 seems to be the best try. Burgess, et al. offer several detailed lines. I am presenting a fraction of these here with a few improvements made possible by stronger computers in the nearly twenty years since their book was published.

a) 30.Qc7+ Kg8 and the e-pawn needs protection, according to Burgess et al. Even so, Stockfish likes 31.Qd6 with a clear advantage for White.

b) 30.Ba3 Qd8 31.Qf4! is better than the suggestion in Burgess, et al. (31.Ne2) White seems to have the upper hand.

c) 30.Ne2 Na5 does not seem to lead to victory, as noted by Burgess, et al.

d) 30.h4 credited to Nunn in Burgess, et al. 30...Na5 31.Bc1! Qe7 32.Bg5

d1) 32...hxg5 is an important sideline that Burgess, et al. reject 33.hxg5 Nc6 34.gxf6+ Qxf6 35.Qxd5

|

| After 35.Qxd5 (analysis diagram) |

35...Ne7 seems to hold, according to Stockfish (Burgess, et al. have 35...Nd8)

d2) 32...Nc6 33.Bxf6+ Qxf6 34.Qxd5

|

| After 34.Qxd5 (analysis diagram) |

34...Nd8! (34...Qxh4 is suggested in Burgess, et al. It is the computer's third choice.) 35.Qd7+ Kf8 36.Qc8 and White seems to have a way to victory.

e) Stockfish likes 30.Qd6 30...Na5 31.Bc1 Nc6 32.Qc7+ Ne7 33.Qxa7+-.

Back to the game as played.

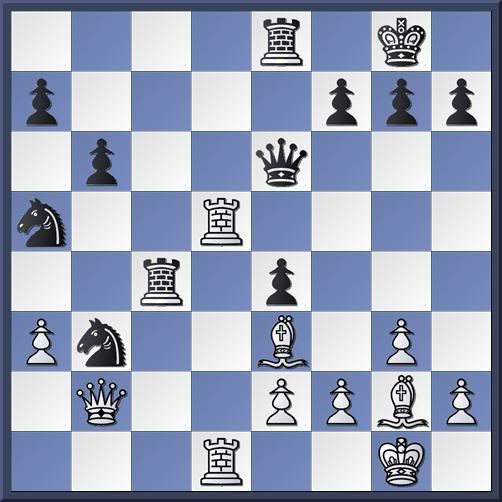

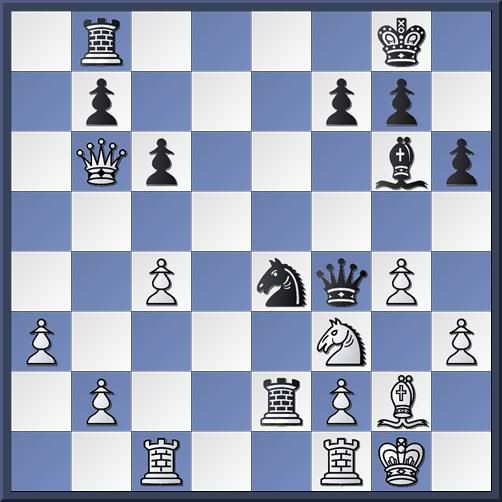

White to move

30.Ba3

The textbook deflection!

30...Qxa3

30...Qe8 31.Qc7+ Kg8 32.Be7 Kg7 33.Bd8+ Kf8 34.Bxf6+-.

31.Nh5+ gxh5 32.Qg5+ Kf8 33.Qxf6+ Kg8 34.e7

34.Qf7+ also wins.

Black to move

For White's deflection to assure victory, he has to foresee this position and calculate to the point where Blaack runs out of checks.

34...Qc1+ 35.Kf2 Qc2+ 36.Kg3 Qd3+ 37.Kh4 Qe4+ 38.Kxh5 Qe2+ 39.Kh4 Qe4+

39...Qe1+ 40.g3 h5 41.Qg6+ Kh8 42.e8Q+

40.g4 Qe1+ 41.Kh5 1–0

Botvinnik won because his strategy was superior, and because he found the necessary tactics when they appeared on the board. This game is worthy of consideration as one of the best. Even so, Capablanca's surprising strategic errors in the late stages of the opening mar it somewhat.

*I suspect that whoever annotated this game for ChessBase MegaBase wrote these words, but I do not have MegaBase.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)