There are other ways to define the principle of development (see "What is Development"). The paragraph above is an effort to present the essence of the oldest definition of the principle that I have found in print. That definition is a translation of writing by Domenico Lorenzo Ponziani (although credited to Ercole del Rio by the translator). It was published in English 17 years before Paul Morphy was born (see "Principle of Development: Early History").

Morphy is usually credited as the "first player to understand the importance of swift development in open games", as Thomas Engqvist puts it in 300 Most Important Chess Positions (2018), 13. Engqvist offers 30 key positions from 24 games to articulate the concept of development in practical ways (13-32). There should be no question that Morphy's games illustrate well the principle of rapid development. They also show, as Engqvist elucidates well, how to sacrifice material to gain a decisive advantage against a player who neglects the principle.

I have spent that past ten days working through these 30 key positions as part of an effort to read the whole of Engqvist's book in 60 days (see "60 Days, 300 Positions: Day One"). This morning I reviewed all thirty positions after spending some time (too little) on numbers 26-30. I noted the key ideas that Engqvist offers through these positions, questioning how much was absent from Ponziani's articulation of the principle.

Engqvist includes center control, which I do not see in Ponziani's statement. He also shows Morphy's preference for avoiding "unproductive one-move threats" (14). Some of the most challenging positions in the first section of the book feature positions from modern grandmaster practice where the idea is to interfere with the opponent's harmonious development. The translation of Ponziani states,

Whoever, at the beginning, has brought out his Pieces with greater symmetry, relatively to the adverse situation, may thence promise himself a fortunate issue in the prosecution of the battle.In the context, I suspect that harmony might make more sense than the word symmetry, but I have not examined Ponziani's Italian. Nonetheless, it is clear that the notion of attentiveness to the opponent's development exists in Ponziani's formulation.

J.S. Bingham, The Incomparable Game of Chess (1820), 32.

William Steinitz is often credited with articulating the principles underneath Morphy's play. But, clearly other chess writers before Steinitz mentioned the principle of development. As for Morphy being the first to understand rapid development, I offer this position, which would be in my collection of 300 most important positions.

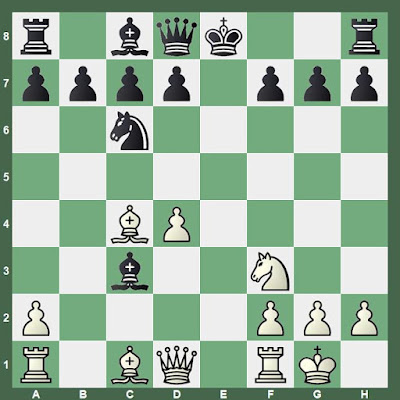

White to move

White has already sacrificed two pawns and here often plays 10.Qb3, sacrificing a rook for a winning attack. Black's best chance is 10...d5 11.Bxd5 O-O, as was played in Meyer,H. -- Ubbens,MH., 1926. Gioachino Greco is credited with the position and has both 10...Bxd4 and 10...Bxa1 for Black. In fact, Greco copied this position from the manuscripts of Giulio Cesare Polerio, or perhaps a book by Alessandro Salvio (see "Greco Attack Before Greco").Searching ChessBase Mega 2024 for the position turns up nine games with 10.Qb3 prior to the first with 10.Ba3, which might be an improvement (see "Corte -- Bolbochan 1946").

After 10...Bxa1 in Polerio's composition, we have a position that I like to show students in conjunction with this position from Morphy's Opera Game.

White to move

In both cases, White is behind a considerable amount of material but completely winning because Black's pieces lack mobility. It seems clear to me that Polerio and to an even greater extent Greco understood the pitfalls in neglecting the principle of development. It remained for the leading players of the so-called Italian school a century later to articulate the principle.Nonetheless, Morphy's games remain the clearest early examples.