The shared quote inspired me somewhat two days after I read it on Facebook. While going through a long and difficult game that I won, my opponent and I were examining a position that had occurred one-third of the way through the game. I was clearly worse. "You should have resigned," Mark said. My position was quite bleak. I was down an exchange plus pawn and my pieces had no play.

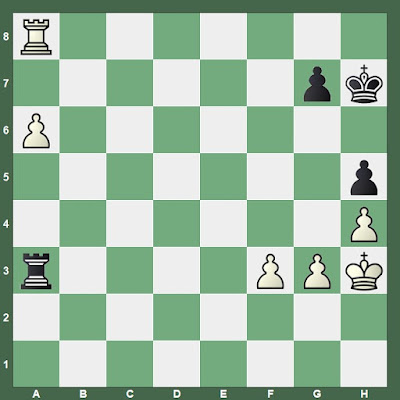

Black to move

|

| Havrilla -- Stripes 2025 |

Perhaps it was about this time that I walked over to the wall charts to see Mark's rating. It was close to mine (ten points lower). We were both low-A Class. I've been A-Class long enough to know that anyone at such a level probably has defects in their game.

My position was clearly worse, but my opponent still had some work to perform. A resignable position in my view is one where I could turn the board around, take my opponent's side, and defeat Magnus Carlsen, or Stockfish, or Carlsen and Stockfish working together.

Donner's assertion, which I could no longer find where I'd remembered seeing it on Facebook, was made in the context of two games he played against Borislav Milic in a match between Yugoslavia and the Netherlands. Although Donner reached a clearly superior position in both games, he managed only half a point.

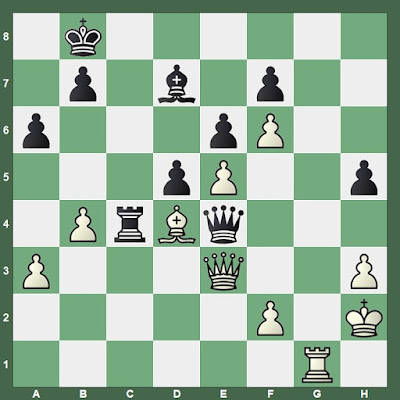

Black to move

|

| Donner -- Milic 1950 |

In comments on the position above, he wrote, "Decent players resign in such a position. Black did not and managed a draw" (19).

Knowing that my opponent was quite strong, but not so strong that a few errors might led me swindle a draw from my nearly hopeless position, I opted to play on.

Twelve moves after the position that Mark and I were examining postgame when he thought that I should resign, I snatched an important pawn with 33…Nxa4.

White to move

|

| Havrilla -- Stripes 2025 |

My game remained objectively worse, but at least my pieces had some play. While discussing the game afterwards with some others at the tournament, I described my knight as a fly buzzing in my opponent's face. I expressed some empathy for the difficulty of contending with such irritation.

The game continued, 34.Rc8 Bc5+ 35.Kg2 Rxc8 36.Bxc8 Nxc3 37.Rc1 Ne2 38.Rf1 b6

White to move

|

| Havrilla -- Stripes 2025 |

I began to feel that a draw was a real possibility. After 39.Kf3 Nd4+ 40.Kg4 a4! I was certain that I could hold the game.

Neither of us played the best moves from this difficult position, but after another twenty moves, I was clearly winning. My opponent was also desperately short of time.

White to move

|

| Havrilla -- Stripes 2025 |

Five moves later, my pawn was sitting a2, I had my queen near to hand, and my opponent's clock expired.

In Donner's first game with Milic, he spent an hour on this position.

Black to move

|

| Milic -- Donner 1950 |

Stockfish 17 favors the move that he played, 22...Rg8, but he suggested several others as better, writing without the benefit of computer analysis in 1950. Nonetheless, his advantage began to slip away and the clock also had become an issue by the time Milic had a clear advantage.

This loss and the draw that followed led Donner to offer what became an inspirational quote for me after Mark's postgame comment.

I love all positions. Give me a difficult positional game, I'll play it. Give me a bad position, I'll defend it. Openings, endgames, complicated positions and dull, drawn positions, I love them all and will give them my best efforts. But totally winning positions I cannot stand. (19)Later in the same paragraph is the statement that I used as an epigraph last week while annotating an ending where imperfect play on both sides gave me drawing chances that I missed, followed by my opponent missing his winning chances, and eventually the draw falling into my lap (see "Comedy of Errors"): "It is much better, in fact, to play an objectively less correct game but to be able to win once you've got a winning position" (19).