Game of the Week

After languishing on my shelves for a decade or longer,

Chess: The Art of Logical Thinking (2005) by Neil McDonald came off for some serious study. Marginalia on many pages reveals that I have previously worked through the first several games, but have not worked through the whole. I spent half a morning last week creating a database with all thirty games and then racing through all of them for a first look. The next step was to work through the first game carefully before reading what McDonald has to say about it.

The plan is to study each game, then read McDonald's comments. I followed this process with the games in Irving Chernev,

Logical Chess: Move by Move (1957). McDonald follows Chernev's classic by commenting on every move.

The first game in McDonald's book is the game that began with Victor Kortschnoj* holding out his hand before the game, only to be snubbed by Anatoly Karpov who said he he would no longer shake hands because of Kortschnoj's behavior. The behavior in question concerned his complaint about the seating in the audience of Dr. Vladimir Zukhar, a parapsychologist who was part of Karpov's team. Kortschnoi wanted Zukhar further back from the stage where the match took place. This game was the eighth in the championship and the first that was not drawn. Karpov went on to win the match, reaching his sixth win in game 32. Kortschnoj won five games.

McDonald does not discuss this historical background, despite his comment in the Introduction:

[P]sychological factors should be considered. ... When there is no obvious right or wrong, the character of the player has a major impact on the decision taken. This can be for both good and bad as the games of even the greatest players are frequently won and lost by impulsive or inspired decisions.

McDonald, Chess: The Art of Logical Thinking (5-6)

Karpov,Anatoly (2725) -- Kortschnoj,Viktor (2665) [C80]

World Championship 29th Baguio City (8), 03.08.1978

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6

What are the merits of the Morphy variation? McDonald does not ponder this question, nor offer much help towards an answer. He does dress the move 3...a6 with an exclamation mark.

4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0–0 Nxe4

Black temporarily wins a pawn. The exchange of center pawns shifts the focus towards active piece play. Playing through this game, I game to realize that my understanding of the Open Spanish is somewhat underdeveloped. It's not something I've played as Black, nor often faced as White.

5...Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3

6.d4 b5

6...exd4 seems dubious 7.Re1 f5 8.Nxd4 Be7 9.Nxf5 d5

7.Bb3 d5

7...Na5? invites tactics

a) 8.Bd5 c6 9.Bxe4

b) 8.Bxf7+!? Kxf7 9.Nxe5+ Kg8

b1) 9...Ke6 10.Qg4+ Ke7 11.Qxe4;

b2) 9...Ke8 10.Qh5+ g6 11.Nxg6 hxg6 (11...Nf6 12.Re1+ Be7) 12.Qxg6+ Ke7 13.Bg5+ Nxg5 14.Qxg5+ Kf7 15.Qxd8; 10.Qf3 Qf6 (10...Nf6 11.Qxa8; 10...Qe8 11.Qxe4) 11.Qxe4 Bb7 12.Qd3)

8.dxe5

This pawn will not be easily removed by Black and controls some key dark squares.

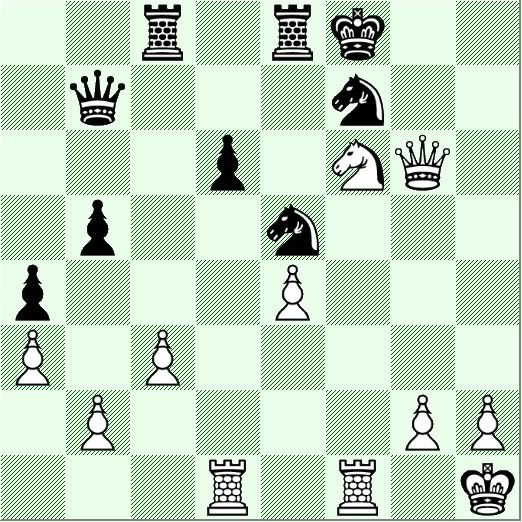

8...Be6

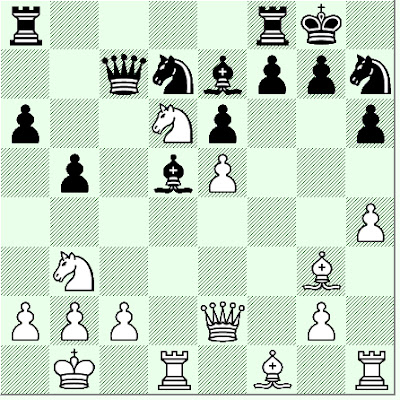

White to move

There are things that I don't like about Black's position: the backwards c-pawn, placement of the bishop in the pawn chain, and White's pawn striking at f6 and d6. But, Kortschnoj understood these consequences of his fifth move. This position has been played many thousands of times by top players with many Black wins. White's overall score is strong, but Kortschnoj's wins with Black include such opponents as Tal and Petrosian, and even Karpov later in this match.

My database contains 97 games with this position and Kortschnoj as one of the players, nearly always as Black. The overall score is 50% with 24 wins for each side and the rest draws.

My assessment of this position was skewed by lack of familiarity with the Open Spanish compounded by the tendency to annotate by result. Because Kortschnoj lost, I was looking for defects very early in the game. However, this position is an interesting tableau in the Spanish.

9.Nbd2 Nc5

9...Nxd2 Seems plausible and has been attempted by strong players, but with a score exceeding 75% for White. 10.Bxd2 Be7 (10...Bc5)

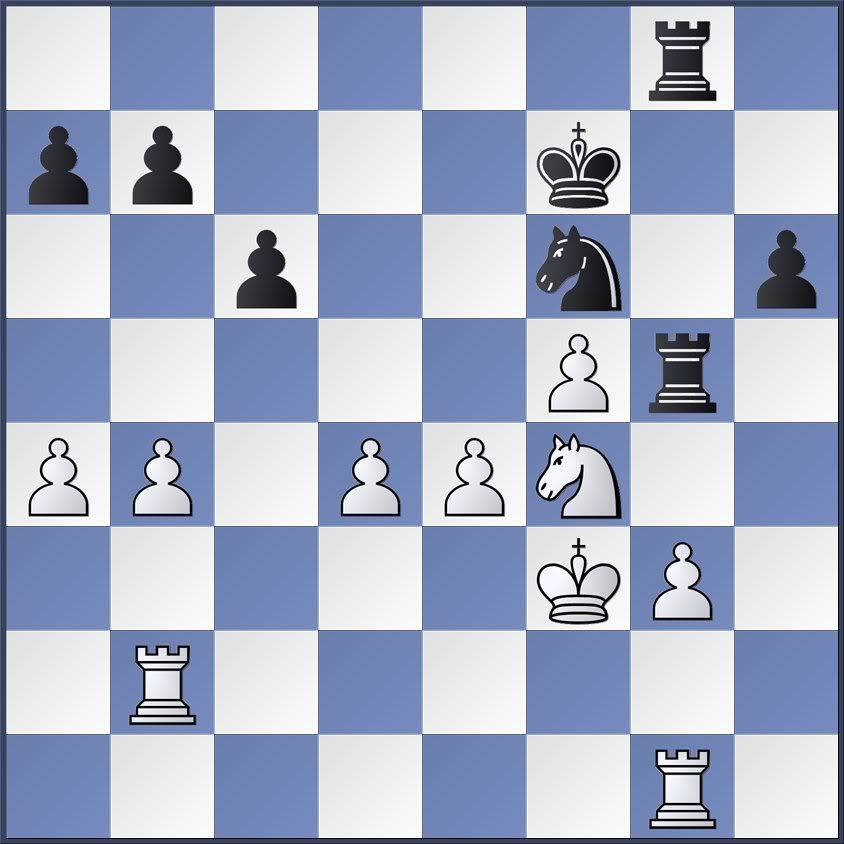

10.c3

Is White already slightly better? Black's light-squared bishop is part of a pawn chain, while White's e-pawn puts a clamp on the dark squares. Meanwhile, Black's king remains in the middle of the board. This position has appeared well over 1800 times in the annals of chess with a 58% score for White, but with over 400 Black wins.

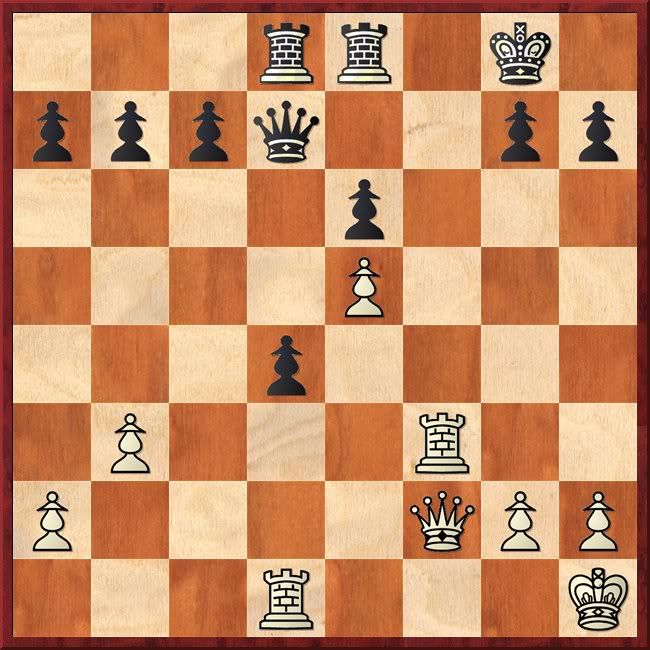

Black to move

10...g6?!

This move was criticized by Raymond Keene and others. Keene's criticism appears in a book that I bought about forty years ago, when it was new: Raymond Keene,

The World Chess Championship: Korchnoi vs. Karpov (1978), which claims to be the "inside story of the match". Keene was part of Kortschnoj's team. However, another book suggests that Keene was too much focused on journalistic dispatches to England to be an effective team player.

Persona Non Grata (Thinkers' Press, 1981) lists as authors Viktor Kortchnoi with Lenny Cavallaro. However, Kortschnoj is consistently referred to in the third person in this book, suggesting that Cavallaro may have had the leading hand as author.

Persona Non Grata offers an account of the snub.

The 8th game. Viktor arrived at the table; Karpov did not get up. Kortchnoi sat down and held out his hand. Karpov replied that from that moment he had no intention of giving him his hand. ... The shot hit home. Kortchnoi played a poor tenth move (among others); Karpov conducted his attack quite well. (39-40)

What were the alternatives? Four moves have been played more often that Kortschnoj's.

a) 10...Nxb3 is fourth most popular 11.Nxb3 Be7

b) 10...Bg4 is third in popularity and Black has done well

c) 10...d4, the second was popular move was played by Kortschnoj later in this match, and three times in the 1981 match.

d) 10...Be7 strikes me as simple. It is the most popular move. There is no rush to castle as the king might find safety on the queenside or be needed for an endgame.

e) 10...Nd3 ihas been played less often than 10...g6, but still appears in more than two dozen games. 11.Qe2 is the usual continuation 11...Nf4 12.Qe3 g5 13.Rd1.

11.Qe2

Kortschnoi repeated his 10...g6 twice in later years, leading to

a) 11.Re1 Nd3 12.Re3 Nxc1 13.Rxc1 Bh6 14.Rd3 0–0 15.Qe2 Ne7 16.Rd1 c5 17.Bc2 Bf5 18.Nf1 Bxd3 19.Bxd3 Qc8 and White won in 87 moves, Fedorchuk,S (2564) -- Kortschnoj,V (2634) Warsaw 2002.

b) 11.Bc2 Bg7 12.Re1 Nd7 13.Nd4 Nxd4 14.cxd4 and drawn in 28 moves, Almasi,Z (2676) -- Kortschnoj,V (2632) Budapest 2003.

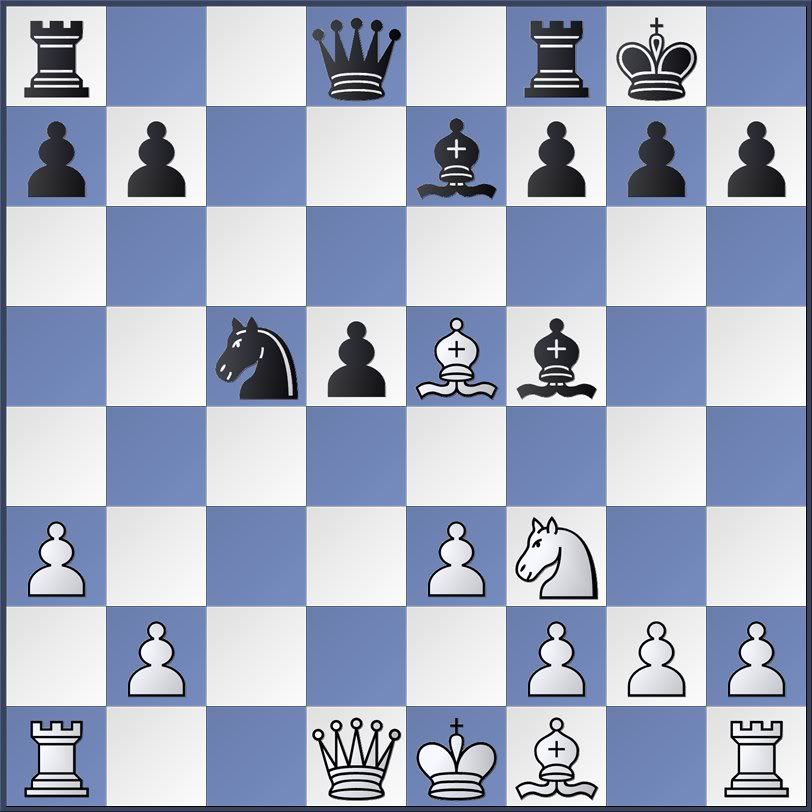

11...Bg7 12.Nd4!

Kortschnoj believed this pawn sacrifice was not in Karpov's character, or so Keene claimed.

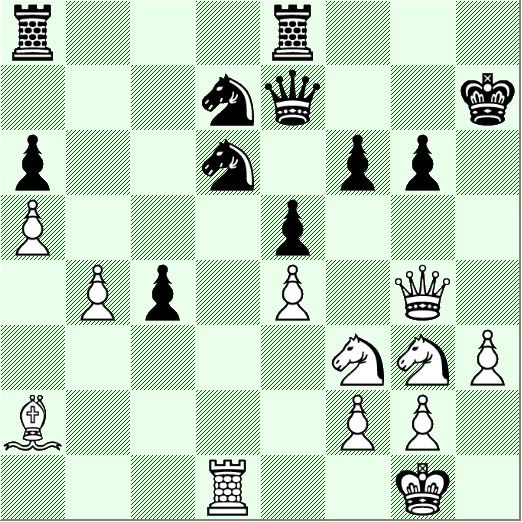

Black to move

12...Nxe5

12...Nxd4 13.cxd4 Nb7 (After 13...Nxb3 14.Nxb3 0–0 McDonald points out a simple winning plan--moving all the heavy pieces to the c-file to hammer away at the backwards c-pawn.)

12...Qd7 is favored by McDonald and was played by Mihai Marin in 2007: 13.f4 0–0 and Black won in 45 moves, Thesing,M (2393) -- Marin,M (2551) Predeal 2007.

13.f4

I thought that Black was already in deep trouble at this point, but in 2012 Sarunas Sulskis went on from here to win with Black.

13...Nc4

13...Ned3 was Sulskis's choice. 14.f5 (14.Bc2 Nxc1 15.Raxc1 0–0) 14...gxf5 15.Nxf5 Rg8 16.Bc2 Sulskis seems to have taken the weaknesses of Kortschnoj's position and turned them into strengths. 16...Qg5 17.Nxg7+ Rxg7 18.Nf3 Nxc1 19.Raxc1 (19.Nxg5 Nxe2+ 20.Kh1 Rxg5–+) 19...Qg4 There is not much left of White's attack. 20.g3 Ne4 21.Qg2 Qh5 22.Rfe1 0–0–0 and Black went on to win in 71 moves, Azarov,S (2667) -- Sulskis,S (2595) Jurmala LAT 2012.

14.f5 gxf5 15.Nxf5

Black to move

Black has won even from this position, but there was a rating gap over over 400 Elo favoring the second player.

15...Rg8±

I think that Karpov has the upper hand at this point in the game.

15...Bf8 16.Nf3 Ne4 17.N3d4 c5 18.Nxe6 fxe6 19.Qh5+ Kd7 20.Bxc4 bxc4 21.Ne3 Nd6 22.Ng4 Bg7 23.Bg5 Qe8 24.Qh3 h5 25.Nf6+ Bxf6 26.Bxf6 Rf8 27.Rad1 Kc6 A secure king! 28.Rde1 Ne4 29.Be5 Qg6 30.b3 Rf5 31.Rxf5 Qxf5 32.Qxf5 exf5 33.bxc4 dxc4 34.Rf1 Rf8 35.Rf4 Kd5 36.Bg7 Rf7 37.Bh8 Ke6 The bishop is trapped 0–1 De Coverly,R (1992) -- Sarakauskas,G (2415) Bournemouth ENG 2015.

16.Nxc4 dxc4

16...Nxb3 17.axb3 bxc4 18.bxc4 Black's king will suffer.

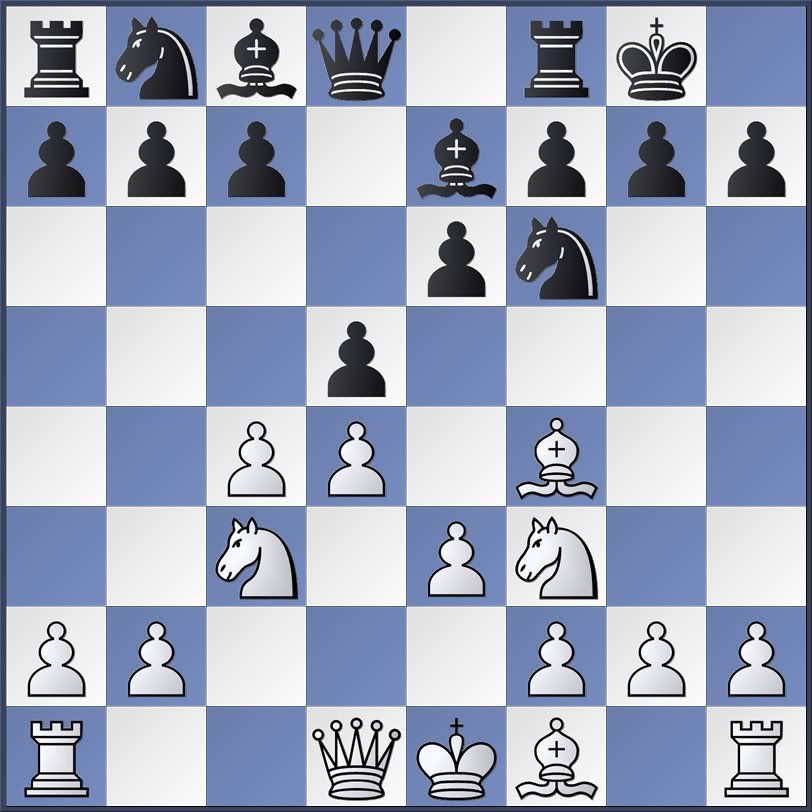

17.Bc2 Nd3 18.Bh6 Bf8

18...Bxh6 was more stubborn 19.Nxh6 Rg7 (19...Rg6 20.Nxf7) 20.Nf5 Rg6 (20...Rg8 21.Rad1) 21.Rad1

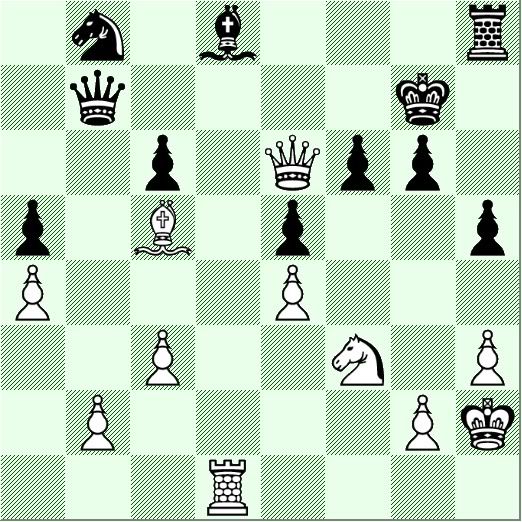

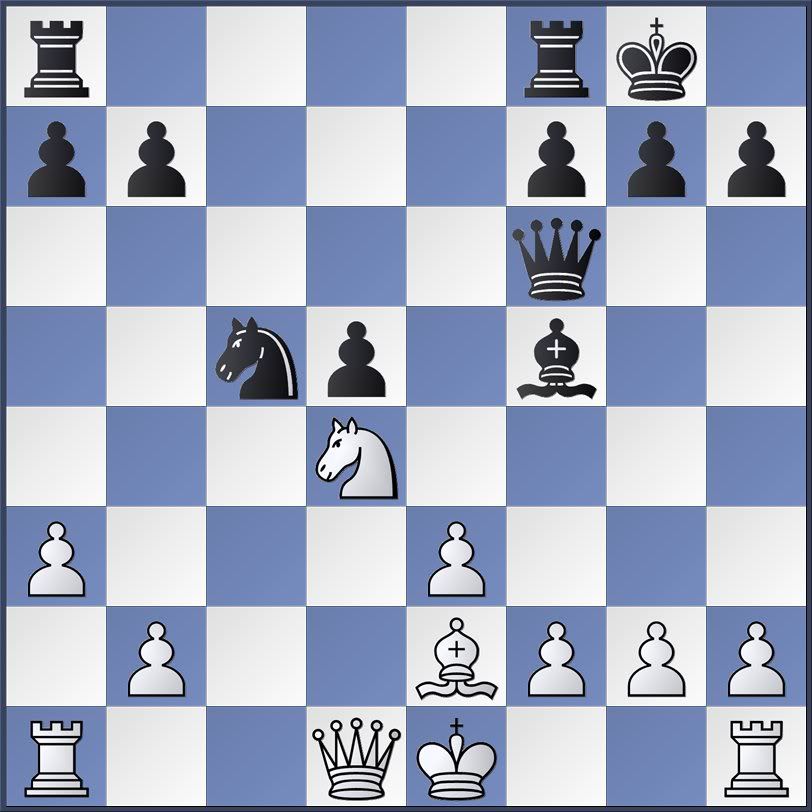

White to move

19.Rad1+–

Black's king is stuck in the middle. All White's pieces are in the attack, while Black's pieces are mostly tied down or watching helplessly.

19...Qd5

19...Bc5+ 20.Kh1 Qd5 21.Bxd3 cxd3 22.Rxd3 Qc6 23.Ng7+ Rxg7 (23...Ke7 24.Bg5+ Kf8 25.Nxe6+ and checkmate is coming soon) 24.Bxg7 Bd6+-

20.Bxd3

White's decisive final attack brings pressure along the three central files d-f. McDonald emphasizes the absence of Black's queen's rook from the battle. This decisive blow had to happen now, or Black would castle queenside and have exceptional counterplay. In such a case, Black's wrecked kingside pawn structure becomes rather an open line against White's monarch.

20...cxd3 21.Rxd3 Qc6 22.Bxf8 Qb6+

This move gains a necessary tempo, but is not enough to save the game barring a blunder from Karpov.

22...Kxf8 23.Nd4 Qb6 24.Qxe6 Kg7 25.Qxb6 cxb6+-

23.Kh1 Kxf8

McDonald points out 23...Rxf8 24.Qf3 Rd8 25.Ng7+ Ke7 26.Qf6#

24.Qf3 Re8 25.Nh6

Wasn't f7 the target when White played 1.e4?

Black to move

25...Rg7

a) 25...Ke7 26.Nxg8+ Rxg8 27.Qf6+ Ke8 28.Rd8#

b) 25...Kg7 26.Qf6+ Kf8 27.Nxf7 Qc6 (27...Qb7 28.Nd8+ Bf7 29.Qxf7#) 28.Ne5+ Bf7 29.Qxf7#

c) 25...Rg6 26.Qxf7+ Bxf7 27.Rxf7#

26.Rd7

All four of White's pieces aim at f7. This move seems obvious in retrospect, but perhaps is not immediately obvious. McDonald gives it a double exclam, calling it "The star move" (17).

26...Rb8

26...Bxd7 27.Qxf7+ Rxf7 28.Rxf7#

27.Nxf7 Bxd7

a) 27...Ke8 28.Ne5 Rg8 (28...Rxd7 29.Qf8#) 29.Qf6 Qd6

a1) 29...Bxd7 30.Qf7+ Kd8 31.Qxd7#

a2) 29...Qc5 30.Qxe6+ Qe7 31.Qxe7#

30.Rxd6 cxd6 31.Qxe6+ Kd8 32.Qd7#

b) 27...Bxf7 28.Rxf7+ Kg8 29.Rf8+ Rxf8 30.Qxf8#

28.Nd8+

Black resigned.

28...Bf5 is the only defense against checkmate 29.Qxf5+ Ke7 30.Qf8+ Kd7.

1–0

McDonald's annotations are light, focusing on the essential position elements in the game with a few tactical variations.

*Spelling note: I favor the spelling of Viktor Kortschnoj that is used in Chess Base for this post, but where the name in quotes or front matter of books, I retain the spelling employed in those books.