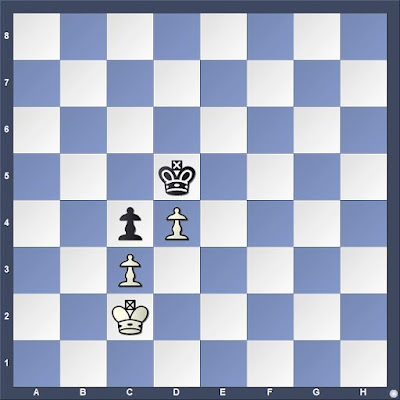

White to move

Chernev explains, "White abandons his passed pawn. Capturing it will keep Black busy on one side of the board, while White gets time to win on the other" (39). He gives the moves:1.Kf5 Kh6 2.Ke5 Kxh5 3.Kd5 Kg6 4.Kc6 Kf6 5.Kxb6 Ke7 6.Kc7

When young players learn this simple idea, they have a requisite skill for navigating a great many pawn endings that will occur in their own games.

Chernev gives a second solution that employs a fundamentally different set of principles, but that leads to a faster checkmate. Hence, the position is less than ideal for my purposes. Even so, I had the exact position in a blitz game in July 2021 and played it according to book.

Silman's illustration is cleaner. While there are several winning moves that can be played, his solution appears to follow the top engine moves.

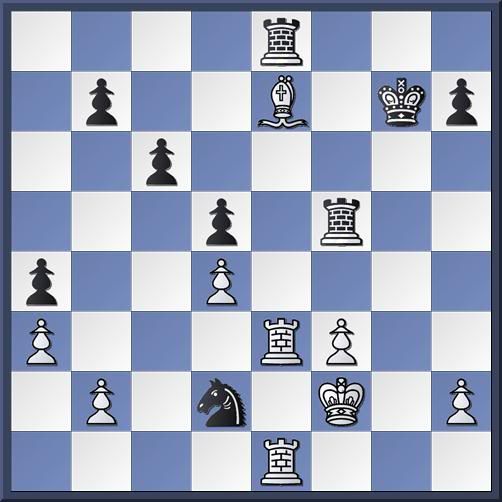

White to move

1.b5 Kb7 2.Ka5 Ka7 3.b6+ Kb7 4.Kb5 Kb8 5.Kc6 Kc8 6.Kd6 Kb7 7.Ke6 Kxb6 8.Kxf6 Kc7White to move

9.Kxg5

Silman writes, "the rest is mindlessly easy" (67).

I would play 9.Ke7, which wins faster.

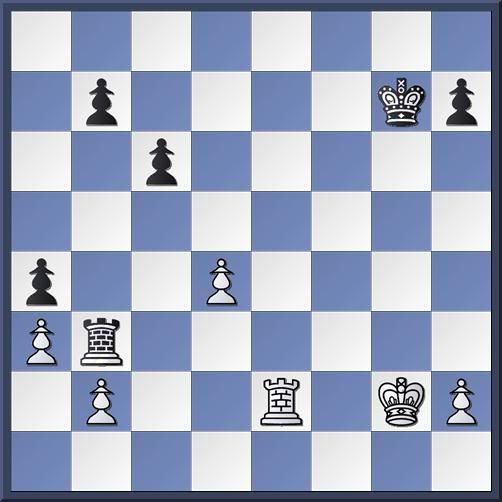

When teaching or testing students, I usually compose positions on the spot. But, perhaps it would be useful to have a printed sheet in my chess bag with some of the most instructive positions from books and game. Paul Keres, Practical Chess Endings (1974) offers one that is excellent. His term is "distant passed pawn" (55). As he notes, without the passed pawn that will be sacrificed (or exchanged for Black's passed pawn), White would be lost.

1.f5 Ke5 2.f6 Kxf6 3.Kxd4 Ke6 4.Kc5 Kd7 5.Kxb5 Kc7 6.Ka6Silman writes, "the rest is mindlessly easy" (67).

I would play 9.Ke7, which wins faster.

When teaching or testing students, I usually compose positions on the spot. But, perhaps it would be useful to have a printed sheet in my chess bag with some of the most instructive positions from books and game. Paul Keres, Practical Chess Endings (1974) offers one that is excellent. His term is "distant passed pawn" (55). As he notes, without the passed pawn that will be sacrificed (or exchanged for Black's passed pawn), White would be lost.

White to move

Reviewing my own internet games stretching back to the late-twentieth century produced many positions where the basic idea of using a passed pawn to deflect the opponent's king from the main scene was required. In many cases, the correct move was not played.

I played it correctly in this position from the Internet Chess Club in 2001.

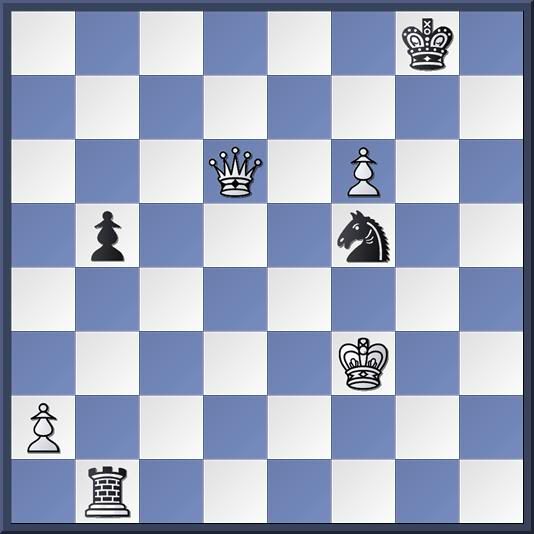

Black to move

38...b3! was the only winning move. My opponent resigned after 39.Kxb3 Kxd5 40.Kc3 Ke4 41.Kd2 Kf3Thinking I was applying this idea, I managed to throw away the win in this game from 2001.

White to move

I played 45.h4 and succeeded in forcing Black's king to the h-file while gobbling Black's two remaining pawns with my king. However, Black's king was able to get back to the a-file in time. This position shows that calculation is necessary in pawn endings and sometimes there is more than one idea in play.1.Kf4! is the only winning move.

If Black then goes after the a-pawn, White needs to win a queen vs. pawn ending where it is important that Black's pawn is two squares from promotion. If the Black king tries to get the the h-file, then the distant passed pawn is far enough away that White will be able to promote the a-pawn.