I have an opponent who plays the Dragon variation of the Sicilian Defense. Rather than playing 1.d4, which is my top choice in USCF rated chess, I plan to court his Dragon. I need to meet players at their strength in order to improve my skill. I do not know how well my opponent understands the Dragon, nor how he has studied the opening. His games on

Chess.com are too few, and his opponents too quickly deviate from sensible book lines.

This post documents my two days of preparation for a single chess game. I am beginning this article on Tuesday morning, the game is scheduled for Wednesday evening, and I plan to post on Thursday.

This game is my second in the 2014 Spokane Contenders Tournament. Participants in this six-player round robin earned their spots. I am in the event because I played in and lost last year's

City Championship Match. The others either won club events or finished near the top in the Grand Prix. The winner of the Contender's Tournament earns a position as challenger in this year's City Championship.

I am the second highest rated player in the 2014 Contender's with a USCF rating of 1917. My opponent is the fifth highest and rated 1694. His rating was provisional this spring. He is a relative newcomer to competitive chess and is improving fast. His first rated event was last August.

Tuesday Morning

After walking my dogs and eating breakfast, I started this blog post.

The Sicilian Dragon is ECO B70-79.* My first step is to open my personal database of previously played games matching those codes and review them. My search turns up 406 games. Reviewing them all would be daunting.

To get some control over this mass of data, I sorted by Black's rating in order to review games against my highest rated opponents. My own name appears near the top in the Black list, indicating that I, too, play the Dragon. I will review those too.

One recurring pattern crops up:

After 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7, I have often played 7.Be2. This move does not score as well as the more popular 7.f3. Even so, it may be worth considering.

Black to move

My post, "

Losing Pawn Wars," came from a Dragon in which I played 7.Be2.

There are also games where I play 6.Be2, which has been played by Kramnik, Kamsky, Nepomniachtchi, and other top Grandmasters. 6.Be2 is the Classical Variation.

Looking through about two dozen games sorted thus, it is clear that my losses are characterized by gross tactical blunders. My wins also profit from blunders by my opponents. The key to my preparation, it seems, should be to seek lines that apply such pressure as to provoke opportunities for miscalculation.

In some losses, I simply drop pawns.

Having spent some time on the model game,

Karpov -- Korchnoi, 1974, it comes as no surprise that I have attempted in online blitz to imitate Karpov's winning strategy. This game is an example of one failure in these efforts.

Stripes (1657) -- Internet Opponent (1819) [B78]

FICS 2013

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0–0 8.Bc4 Nc6 9.Qd2 Bd7 10.Bh6 Ne5 11.Bb3 Rc8 12.0–0–0 Nc4 13.Bxc4 Rxc4 14.Bxg7 Kxg7 15.Nde2 Qa5 16.h4 h5 17.Qg5 Rc5 18.Qe3 Be6 19.Nd4 Bxa2 20.Nxa2 Qxa2 21.Qb3 Qa1+ 22.Kd2 Qa5+ 23.Ke2 Rfc8 24.Qd3 Rc4 25.g4 hxg4 26.fxg4 Nxg4 27.h5 Ne5 28.Qg3 Rxd4 29.Rxd4 Rxc2+ 30.Kf1 Qa1+ 31.Qe1 Rc1 32.h6+ Kh7 33.Ke2 Rxe1+ 34.Rxe1 Qxb2+ 35.Rd2 Qb5+ White resigns 0–1

One factor that looms clear in my review of these games is a lack of precision in the opening. This weakness is not surprising. I have long been of the opinion, expressed frequently in internet forums, that class players should not spend a lot of time studying openings. Rather, tactics and endgames should be the primary focus. Openings can be played on general principles.

Against the Dragon as well as other variations of the Sicilian Defense, I have not developed precise, booked-up responses. Rather, I seek to deploy my pieces to good squares. Most often my bishops go to e2 and e3 with little regard for Black's set-up, but on occasion I will try Bb5 or Bg5. As all of the 400+ games in my database are from blitz, many of these games represent liberal use of premove (making a move on the screen that will be executed after my opponent moves so long as it is legal).

At my current level, however, further progress calls for serious opening study. I need stronger opening preparation to beat the Experts whom I must beat to become an Expert myself. It may be less important to prepare an opening in order to face a B Class player, but is it not a waste of time.

After a bit over an hour reviewing my own games, it seemed time for a quick review of basic ideas and plans as explained by Nick DeFirmian (

Modern Chess Openings, 13th edition [1990]).**

DeFirmian's simple summation is useful for organization.

Yugoslav Attack

"The Yugoslav Attack ... is White's most successful antidote to the Dragon" (246).

My database contains 108 games with the position reached after 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3. I was White in 105 of these, scoring 48-6-51 WDL. Improvement is needed.

Black to move

I find that I am playing h2-h4 too early.

DeFirmian gives as the main line from the diagram 6...Bg7 7.f3 Nc6 8.Qd2 O-O, although Big Database 2012 with The Week in Chess updates reveals that 7...O-O is slightly more frequent than 7...Nc6. The order of popularity at the highest levels, however, is as DeFirmian describes, although 7...O-O remains popular at the top.

In my games, 9.h4 accounts for many of my losses. After 9.Bc4, I score 56.5%. I fare poorly after 9.O-O-O, although that move scores well in Big Database 2012.

Hence, I studied one loss in more detail, with an eye to understanding both the most precise move order and the central ideas.

Stripes,J (1770) -- Internet Opponent (1855) [B79]

Chess.com, 2013

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3 0–0 8.Bc4 Nc6 9.Qd2 Bd7 10.0–0–0

10.h4 is worth considering here.

10...Qa5 11.Nb3?!

Possibly the beginning of my problems. 11.Kb1 and 11.Bb3 are preferred by the top players.

11...Qc7 12.g4?

Another inaccuracy. 12.Bh6 was better.

12...Rfc8 13.Bd5? Ne5 14.Qf2? Nc4 15.Bxc4 Qxc4 16.h4=

That my further errors led to an even game is a symptom of blitz. The value of this game for opening study ends here.

16...a5 17.h5 a4 18.Rd4 Qc6 19.Nd2 a3 20.Rc4 axb2+ 21.Kxb2 Qa6 22.Rxc8+ Bxc8 23.Nb3 Be6 24.Bd4 Qa3+ 25.Kb1 Bc4 26.hxg6 fxg6 27.g5 Nh5 28.Bxg7 Nxg7 29.Qd4 b5 30.f4 Ne6 31.Qd2 b4 32.Nd5 Qxa2+ 33.Kc1 Bxb3 34.Nxe7+ Kf8 35.Nxg6+ hxg6 0–1

I continued this process for a few more games.

Classical Variation

I fare better after 6.Be2 (53.4%). Here, though, my move order rarely follows that DeFirmian gives as the main line, 6...Bg7 7.O-O O-O 8.Be3 Nc6. I tend to play 7.Be3 first. I also castle on the queenside often enough to reveal that I confuse the classical system with the Yugoslav attack.

Levenfish Variation

I find only six games where I played 6.f4 and I lost four of those.

Other Ideas

I find that I have frequently played 6.Bg5, scoring over 53%. This move has been an occasional weapon of top players, but generally scores less well than the Yugoslav and classical variations. I shall concentrate on honing my understanding of the correct move order on those two.

Tuesday Afternoon

It is not possible to spend the whole day studying chess, nor is it productive. The morning session, which was interspersed with other activities, was not highly efficient. But, it did serve to identify weaknesses in my play against the Sicilian Dragon.

My afternoon session was shorter and better focused. I spent an hour going through the B70 lines in the

Encyclopedia of Chess Openings that feature 6.Be2 (the classical variation). These are lines 3-12. they contain an abundance of variations and links to important reference games. The electronic version is a

nice resource.

At this moment, I am aiming for 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be2 Bg7 7.O-O O-O 8.Nb3 Nc6 9.Re1. This plan may change.

Black to move

Ideas here include overprotection of the e4 pawn for when the knight on c3 is kicked, retreat of the light-squared bishop to f1, deployment of the dark-squared bishop on g5 to put pressure on e7 or to provoke h7-h6. Black has many choices. By looking through several of the reference games in ECO, however, I should be familiar with common patterns.

Of course, my opponent has plenty of opportunities to deviate from main lines of the Dragon, to try the Accelerated Dragon, or to avoid the Dragon altogether. He could even try the French.

Tuesday Evening

While sipping wine on the deck with my wife, I spent a little time going through games via the ChessBase iPad app. I set the position in the diagram above as my search parameter. There were several hard-fought draws between 2700+ players.

Wednesday Morning

During coffee, I looked through some games in

Chess Informant, including CI 113/69, from which a position appeared on this blog last October ("

Expose the King").

After walking the dogs and then spending some time at work (I work at home most of the time), I reviewed some recent games via

The Week in Chess. One that went badly for White merits study.

Malloni,M (2350) -- Mogranzini,R (2499) [B70]

46th TCh-ITA 2014 Condino ITA (6.1), 03.05.2014

1.e4 d6 2.Nc3 c5 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 g6 6.Be2 Bg7 7.0–0 0–0 8.Bg5 Nc6 9.Nb3 Be6 10.Re1 a5 11.a4 Rc8 12.Bf1 Nb4 13.Nd4 Bc4 14.Ndb5 Bxf1 15.Rxf1 Qd7 16.Re1 Qe6 17.Rc1 Rc5 18.Be3 Rc4 19.b3 Nxe4 20.bxc4 Nxc3 21.Nxc3 Bxc3 22.Bd2 Qxc4 23.Bxc3 Qxc3 24.Rxe7 d5 25.Re3 Qc4 26.c3 Rc8 27.Rb1 Na2 28.Rxb7 Nxc3 29.Qe1 Ne4 30.Qa1 Qxa4 31.Re1 Qc6 32.Rb2 a4 33.Ra2 Nc3 34.Rd2 Qc5 35.Re3 d4 36.Red3 Rb8 37.Rb2 Rxb2 38.Qxb2 a3 39.Qb8+ Kg7 40.h3 a2 41.Qa8 Qb5 0–1

White's eighth move offers choices. What is the optimal move order? Should White play Nb3 before Black commits to Nc6? Is 8.Bg5 accurate, or should it follow Re1?

Yesterday's move order (above) derives from the

Encyclopedia of Chess Openings. Is it optimal? It also appears in DeFirmian's MCO-13.

8.Nb3 first appeared in

Chess Informant in Timman -- Miles, Luzern 1982 (CI 34/260). It is one of the reference games that I examined during my morning coffee. I marked it as deserving further study. Tony Miles won that game brilliantly, but the next issue of

Informant had a second game with 8.Nb3, which was won by White. Although my search does not turn up earlier instances of 8.Nb3, Miles' annotations identify his 8...Nbd7 as the game's novelty.

Scrolling through the 78 games in CI 1-113 that contain the position after 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be2 Bg7 7.O-O O-O, I find many instances of 8.Kh1, 8.Bg5, 8.Be3, and 8.Nb3. The earliest instance of

8.Re1 appears in Ermenkov -- West, Novi Sad 1990 (CI 50/[233]) and Ermenkov -- Chandler at the same event and with the same CI number. Again, 8.Re1 is not presented as a novelty. Perhaps, transpositions in move order are the reason the move is not considered new.

ChessBase has 8.Re1 in Basman -- Cooper 1972. Cooper's rating of 1830 suffices to keep the game out of

Chess Informant.

The position after 8.Re1 appears in thirteen games in

Informants 1-113. I am going through all of these games and the annotations. Although I remain uncertain that 8.Re1 is the optimal move order, I am leaning towards that move this afternoon. I will hold Nd4-b3 in reserve to meet Nc6 should my opponent play that move before castling.

The Game

Stripes,James (1917) -- Dussome,David (1694) [B70]

Spokane Contenders Spokane, 09.07.2014

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be2 Bg7 7.0–0 0–0 8.Re1 Nc6 9.Nb3

We reached the position that I prepared via the move order I settled upon this morning.

9...Be6 10.Bf1 Rc8 11.Nd5 Ne5!

White to move

Despite my preparation, I had not examined this move.

12.c3

My move has been played by strong Grandmasters, as has the immediate 12.Bg5.

12...Bg4

I expected 12...Nc4, and was not certain that I would play 13.Bxc4.

13.f3 Bd7 14.Bg5

Black to move

14...a5

14...Nxd5 was played in the only remaining reference game.

15.a4

I considered 15.Nxf6, but my hopes of winning the d-pawn were easily refuted. I spent twelve minutes on this move--my longest think of the game. My move is the third choice of Stockfish. 15.Bxf6 was probably best, although I considered this move for only a moment.

15...Nxd5 16.Qxd5?!

Originally, I planned 16.exd5, which was better.

16...Be6 17.Qb5 b6 18.Nd2!?

The computer likes 18.Nd4, which I considered. Despite my 12.c3, I found myself concerned for the safety of my b-pawn as the vulnerability of my queen and knight facilitate Black's efforts to mount an attack.

18...Rc5 19.Qa6 Nc4

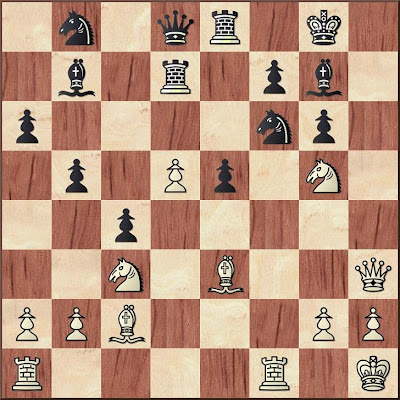

White to move

20.Nxc4

20.Bxe7! would have given me an advantage. I did not spend enough time on this move. My opponent had spent ten minutes on 19...Nc4. I needed to make certain that I understood all that he was looking at.

20...Bxc4 21.Bxe7?

21.Bxc4 Rxg5 was much better, preserving a balanced game.

21...Bxf1!

I missed this move in my calculations. My preparation gave me a position that I liked, although my opponent, too, liked his position. He won because he calculated better than me.

22.Qa7 Rc7 23.Bxd8 Rxa7 24.Bxb6 Ra6 25.Be3 Bc4

White to move

I resigned a few moves later. It was a tough loss, and yet I feel that I gained something from the experience of preparing and playing the Classical Variation against the Dragon. My opponent demonstrated that he understand the Dragon well. His tactical skill is strong. He will become one of our city's top players.

*ECO Code is a trademark of Chess Informant.

**I use an old, out of date edition of MCO because I invested in the

Encyclopedia of Chess Openings, which I use more extensively. I have ECO both in print and electronic formats.