This week is my tenth annual youth chess camp. During this camp, I am making more explicit a training process that I have advocated for many years: work backwards through the game in your study. That is, start with checkmates, move from there to endgames, then study tactics and middlegame strategy, and only then examine the opening. Finally, look at whole games. Repeat this sequence with more advanced materials. Keep repeating the sequence from the end to the beginning to the whole.

This process is the structure of Jose R. Capablanca,

Chess Fundamentals (1921), which I have long advocated as among the best books for beginners and intermediate players. This process is the structure of my camp workbook for this year,

Five Days to Better Chess: Essential Tools, which I have made

available through Amazon.

Students begin each day with a warm-up exercise. The first day's warm-up consists of questions two and three from a test administered for several years by Richard James, and presented in "Chess Thinking Skills in Children," in

The Chess Instructor 2009, edited by Jeroen Bosch and Steve Giddins.* Each question is a diagram where one must find White's best move (Black has a checkmate threat) and explain the reasons for this move. My quick grading of these warm-ups as students finish will facilitate putting them in groups for additional work on checkmates.

Following a period of individual and group work targeted at each student's skill set, the whole group will come together for a short lecture. These are my notes for the first lecture.

How do you think about checkmate? In order to finish the game well, you need to checkmate your opponent.

Coordination of Forces

Checkmate requires coordination of your pieces, and of their

contacts with your opponent's pieces. The minimum number of pieces that are needed for checkmate are both kings and either a queen or a rook. Examples will be presented.

Checkmating an opponent with only one of your pieces requires the assistance of his or her pieces. For example, a back-rank checkmate requires that a king be hemmed in by at least two of his own pawns. In the diagram below, Black's f-pawn would be unnecessary if the Black king were on h8. A smother checkmate requires three of a king's own forces holding him down.

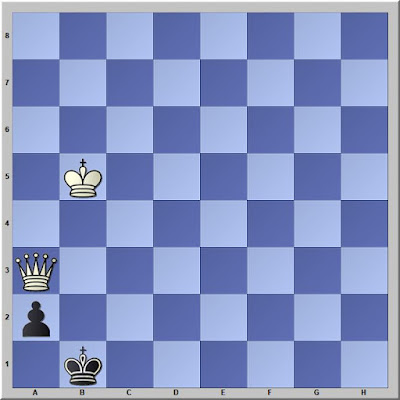

Here we have a corridor checkmate from

Five Days to Better Chess (30). The back-rank checkmate above was presented as a threat that Black had to address.

White to move

Knowledge

There are millions of possible arrangements of the chess pieces to create checkmate.** Nonetheless, most checkmates resemble a few dozen patterns. The better you know these patterns, the more likely you will find checkmate in your games.

Five Days to Better Chess lists 37 patterns, but does not present examples of all of these.

Corridor checkmates--always delivered with a rook or queen--are a family of checkmate patterns that are easy to learn. A back-rank checkmate is the simplest corridor checkmate. In

Five Days to Better Chess, there is a diagram where White threatens this checkmate, but it is Black's move. This position came about in the game Ansaldo,A. -- Boyce,C., Melbourne 1922 in the Championship of Australia.

Black to move

Black found a forced checkmate in six moves. That is an ideal worth striving towards.

22...Rd2+ 23.Bxd2

If 23.Kf1 Qd1#

23.Kh3 leads to a sequence much like the game's finish.

23...Rxd2+ 24.Kh3

This is the position presented in the workbook.

24.Kf1 Qf3+ 25.Ke1 Qf2# Here is another pattern utilizing a queen and rook that one should learn. It is one of the final positions that can occur after a queen and rook roll, discussed at the beginning of the checkmate unit in the book.

24.Qe6+ g4

25.Kh4 Rxh2+ 26.Kg5 Qf6+ 27.Kg4 h5#. Here, we do not have a corridor checkmate, but rather one of those positions that has elements of several named patterns. Observe that Black's queen, rook, and pawn are assisted by White's pawn on g4.

25...Qh6+ 26.Kg3 Qe3+ 27.Kh4 Rxh2#

White to move

White's king is checkmated on the h-file. Two other pieces hold him there: Black's queen covers two squares and a White pawn prevents escape to another. Three squares on the g-file and three squares on the h-file are controlled by Black or occupied by a White piece. Checkmate on the edge requires coordination of pieces to control six squares. This is an example of what I call an "edge-file checkmate", which is similar in important respects to a back-rank checkmate.

Anastasia's Checkmate is another example of a corridor checkmate. Here is one from a Grandmaster blitz game last year, Harikrishna,P. -- Dominguez Perez,L., Huai'an 2016.

Black to move

Defense

Learning checkmate patterns facilitates finding them when you are on the attack. This knowledge also helps when you are defending. When you see the checkmate threats, you can stop them.

In this position from this year's Tata Steel Chess Tournament, Wesley So has Black's king tied down with a rook, and his knight and pawn are well placed to begin working towards an Arabian Checkmate. First, however, he must meet Black's threats.

White to move

42.Kf1 would lose instantly. 42...Qf2#.

42.Kd1 also throws away the win, as So must must avoid Richard Rapport's endless checks that lead to a draw. Nor can White's king find shelter from these checks. 42.Kd1 Nf2+ 43.Kc2 Qxe2+ 44.Kc3 Qe3+ 45.Kb2 Nd3+

White to move (Analysis position)

46.Ka1 walks into checkmate in two.

Facing both checkmate threats and draw by repetition, So played the only move that preserved his advantage, although it also led to a barrage of checks. In this case, however, Black had only one piece harassing the White king, and it was able to find refuge.

42.Qxd3! Qxd3 43.Ng8 Qf3 44.h5! Kh8 45.Rg6 Qh1+ 46.Kd2 Qxe4

White to move

47.Nf6

So threatens checkmate in one.

47...Qb4+ 48.Ke3 and Rapport resigned, as it was clear that he would run out of checks. Black could have tried

Qc5+ 49.Kf3 e4+, but after

50.Kg2, all further checks lose the queen.

Quest for Advantage

Checkmate threats can lead to a material or positional advantage. You threaten checkmate; your opponent sees it and prevents it. There is a simple example of White gaining the advantage of a pawn with a checkmate threat in the section on Legall's Mate in

Five Days to Better Chess.

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 d6 4.Nc3 Bg4?! 5.h3 Bh5 6.Nxe5!

If Black snatches the queen, White has a checkmate in two.

6...Nxe5 7.Qxh5 Nxc4 8.Qb4+ forking knight and king. After Black gets out of check, White grabs the knight. White then has a material advantage of one pawn, as well as more active pieces.

This position from Chigorin,M. -- Judd.M., New York 1889 offers a more complex example.

White to move

20.Rg3

White's rook lift aims for checkmate along the h-file with Rh3, Bxf6, and Qxh7#.

Black's defensive resources are thin due to the cramped position of his pieces. But he finds an ingenious way to avoid checkmate.

20...h6 21.Rh3 Kg8 22.Bxh6 Nd7 23.f6

Black to move

23...Qxf6

Otherwise, 23...Nxf6 24.Bxg7 and White will force checkmate in a few more moves. Students might choose to work out the sequence from here on their own.

24.Bg5 Qh6!

In

Book of the Sixth American Chess Congress (1891), Wilhelm Steinitz wrote:

This ingenious move, whereby Black escapes at the expense of the Exchange from the pressure of an apparently irresistible attack against the King, was probably overlooked by White in his forecalculation on the 23rd move. (35)

25.Qxh6 gxh6 26.Bxh6 Bf6 27.Bxf8 Nxf8

Black survived the mating attack, but White emerged ahead a rook and pawn for a minor piece and went on to win the game.

Everything that we do on the first day will be focused on developing checkmate skills both for attack and defense. The second day, we will work on endings.

*Longer versions of James' original articles are available on his website:

richardjames.org.uk/articles.htm.

**The total number of unique chess positions has been estimated to exceed 10^43 (a one followed by 43 zeros), but most of these, of course, are not checkmate. Even so, my "millions" may be ridiculously low.