A notable feature of this World Championship Match is that both players adopted close to the same openings. Through the first five games, we had four Queen's Gambits Declined. Lasker's defensive position differs from Capablanca's, at least so far, because the elder champion has adopted a dubious advance of his b-pawn.

Now, in the sixth game, we see a repeat of the first thirteen moves of game three, but with colors reversed. For commentary on these first thirteen moves, see "Capablanca -- Lasker, Game 3". That post offers a discussion of some of my sources for annotations. These have improved since it was written. I now have Victor Ciobanu's useful English translation of Lasker's book on the match, which I reviewed on Amazon. In addition, I have a PDF copy of Lasker, Mein Wettkampf mit Capablanca (1926), a second printing of the original 1922 text. Not only do these two texts give me a check on the accuracy of the annotations on two ChessBase DVDs, but Lasker's articles for Telegraaf, a newspaper in Amsterdam, have become accessible because he included them in Mein Wettkampf.

Historical Confusion

Databases all seem to have this game played on Wednesday, 30 March 1921 and Friday, 1 April. These dates seem unlikely. Game five concluded on 30 March (see Capablanca -- Lasker, Game 5 [continued]). Are we to believe that after Lasker's blunder and resignation in game five, they would reset the pieces and the clocks and begin the sixth game? And yet, the summary table of dates, openings, and elapsed time that appears in Capablanca's book on the match shows such overlap.

Could the date in all the databases be due to a clerical error, perhaps by Hartwig Cassel, who presumably created the table? I think that is the most reasonable explanation. American Chess Bulletin (April 1921), which also offers stories of the match that were provided by Cassel, states that game six was played 31 March and 1 April. ACB printed information as they received it during and immediately after the match, while Capablanca's book was put together the month after the match. The information in ACB accords with expectations.

Lasker's book does not contain the table, but Ciobanu's edition, which I believe was translated from the Russian edition (it includes an introduction by Peter Romanovsky), includes a table similar to that in Capablanca's text. Some differences are notable: ECO codes rather than opening names are provided, and the dates given for game six agree with American Chess Bulletin.

Because this game was drawn, perhaps, far fewer annotations have been published over the past century than for the decisive games.

Lasker,Emanuel -- Capablanca,José Raúl [C66]

World Championship 12th Havana (6), 31.03.1921

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5

Capablanca played 3.Nc3, so games three and six diverged until Black's sixth move.

3...Nf6 4.0-0 d6 5.d4 Bd7 6.Nc3 Be7 7.Re1 exd4 8.Nxd4 0-0 9.Bxc6 bxc6 10.Bg5 Re8 11.Qd3 h6 12.Bh4 Nh7 13.Bxe7 Rxe7

"Up to this point the game was identical with the third. Here Lasker changed the course of the game" (Capablanca).

In the table, game three is presented as Four Knights and game six as Ruy Lopez. Ciobanu's version notes that both games are C66, offering a footnote mentioning the transposition from the Four Knights in game three.

"This drives the black queen to e8 and keeps her away from b6. Meanwhile, the white lady stands exposed here" (Lasker).

Ciobanu's translation has a certain elegance worth noting: "This move kicks the Black queen to e8 and cuts off from b6. However, the White queen is now too advanced" (31).

Was Capablanca's 14.Re3 stronger, weaker, or about the same? Perhaps all that matters is that Lasker's choice is different and that changed the game. Stockfish 13 seems to favor 14.Re3, but the difference among more than half a dozen choices is two or three hundredths of a pawn. Several of those other moves were played over the next few moves.

14...Qe8 15.Re2

"This is artificial. Correct is 14.Re3" (Lasker).

15...Rb8 16.b3 c5 17.Nf3

"Not the best. Ng5 was the right move. The text move leaves Black with an exceedingly difficult ending" (Capablanca).

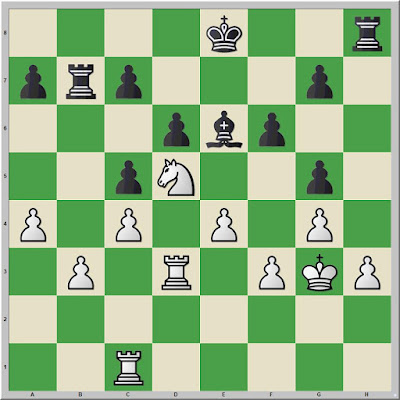

18.Nxb5 Qxb5 19.Qxb5 Rxb5

"With this, a draw is marked" (Lasker).

20.Kf1 Ng5

"Black uses the knight very skillfully. Of course, nothing comes out of all of this. You can do almost any maneuver with the minor pieces in balanced positions, as long as they do not change the situation significantly" (Lasker).

21.Nd2 Ne6

"The maneuvers of this Knight are of much greater importance than it might appear on the surface. It is essential to force White to play c2-c3 in order to weaken somewhat the defensive strength of his b-pawn" (Capablanca).

"Again the moves of the Knight have a definite meaning. The student would do well to carefully study this ending" (Capablanca).

24.Re3 Ng6 25.Nd2 Rb8 26.g3 a5 27.a4

"It is now seen why Black had to compel White to play c2-c3. With the White pawn at c2 Black's game would be practically hopeless, since White's b-pawn would not have to be protected by a piece, as is the case now" (Capablanca).

"An attempt to get the king between enemy pawns, but with insufficient strength" (Lasker).

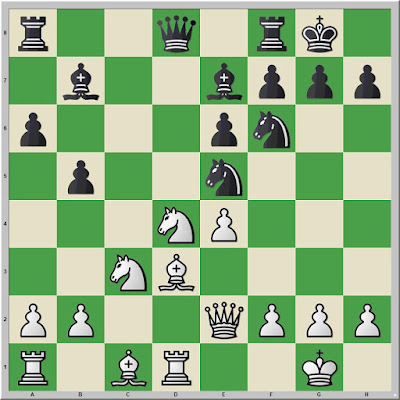

32.e5 "would have lead to a much more complicated and difficult ending, but Black seems to have an adequate defense by simply playing 32...fxe5, followed by d5 when White retakes the pawn" (Capablanca).

32...Nxc4 33.Kxc4 Re6

"This is the best move, and not Ke6, which would be met by Rd3" (Capablanca).

34.e5 fxe5 35.fxe5 d5+ 36.Kxc5 Rxb3

"The white king has fought his way through. Admittedly, it is not enough for a forced win" (Lasker).

"White makes a serious mistake that costs a pawn. After all, 37.Rf1+ would have set more problems for Black. If 37...e7 38.h4 Rg6 39.Rf4 is threatening for White. Black would then probably move 39...h5 40.Rf3. White has the initiative" (Lasker).

"Not the best, but at any rate the game would have been a draw. The best move would have been Rf1+" (Capablanca).

37...dxc4

"Now White must seek a draw" (Lasker).

38.Re4

"Probably the only way to obtain a sure draw" (Capablanca).

Lasker 2:30 - Capablanca 2:30

"There was not any object for either player to attempt to win such a game" (Capablanca).