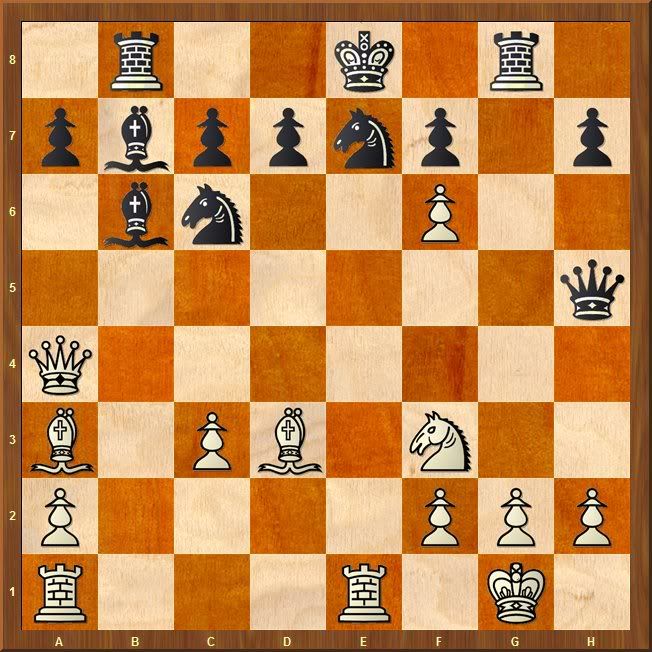

Anyone familiar with the Evergreen Game: Anderssen-Dufresne, Berlin 1852 instantly recognizes it as the position just before 19.Rad1. Was Anderssen's move the best in the position?

Dufresne responded with 19...Qxf3, threatening checkmate in one, but it is a losing move. Anderssen's stunning sacrifice first of the exchange, then of his queen earned the game's nickname. But, Dufresne had other, better moves.

19...Qh3 is hard to find, but forces 20.Bf1.

19...Bd4 offers a bishop to create interference in White's plans.

Addendum: 8 March 2010

Saturday morning, during check-in for a scholastic tournament I ran, I wrote down this game from memory up to the position after 19.Rad1. I had two purposes: check my memory (I made one error), and present a problem to a sixth grader to mull over after she finished her warm-up game with her father. With the help of a seventh grader, she analyzed the game and found an answer to my question: How can Black's play improve over the 19...Qxf3 played by Dufresne?

The two girls offered 19...Ne5.

Another coach and I spent a few minutes at the start of round three looking at their idea. We failed to find the refutation, which consists of three consecutive only moves by White. I found the first move, but not the second, and thus rejected the first in favor of 20.Be4, which fails to three separate alternatives for Black.

The Evergreen Game is well named not only for the stunning finish, but for the complexity of unplayed variations. Black's position has an abundance of resources. If not for the single game losing error on move 19, the result might have been quite different.

No comments:

Post a Comment