The catalog description of GM-RAM: Essential Grandmaster Chess Knowledge (2000) by Rashid Ziyatdinov with Peter Dyson intrigued me and I decided to order it as part of an array of chess books and equipment. When I received the order a few weeks later, GM-RAM was not in the shipment. It was out of stock. Ten years later, I searched online through the collections of several used books stores and bought a copy still in pristine condition. The used price was a few dollars more than it had cost new, but the bookstore shipped it the first business day after my order. It arrived in the mail last Wednesday.

Although I found the catalog description appealing, others failed to read it, ordered the book, and then disliked what they received.

Contains positions only, no analysis.The publisher, the author, and some reviewers— positive and negative, describe this distinctive feature of this book: it contains diagrams without analysis. The author does not indicate the player on move. For some positions, one diagram thus becomes two elementary positions.

USCF Catalog, c. 2000

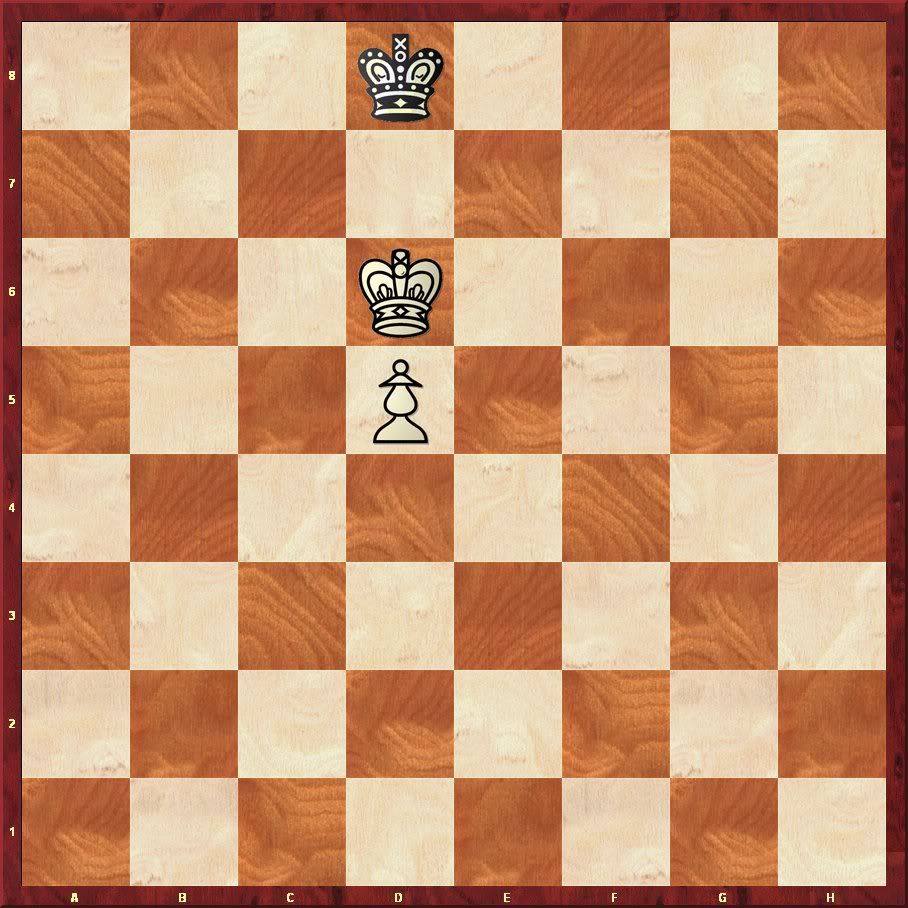

White wins.

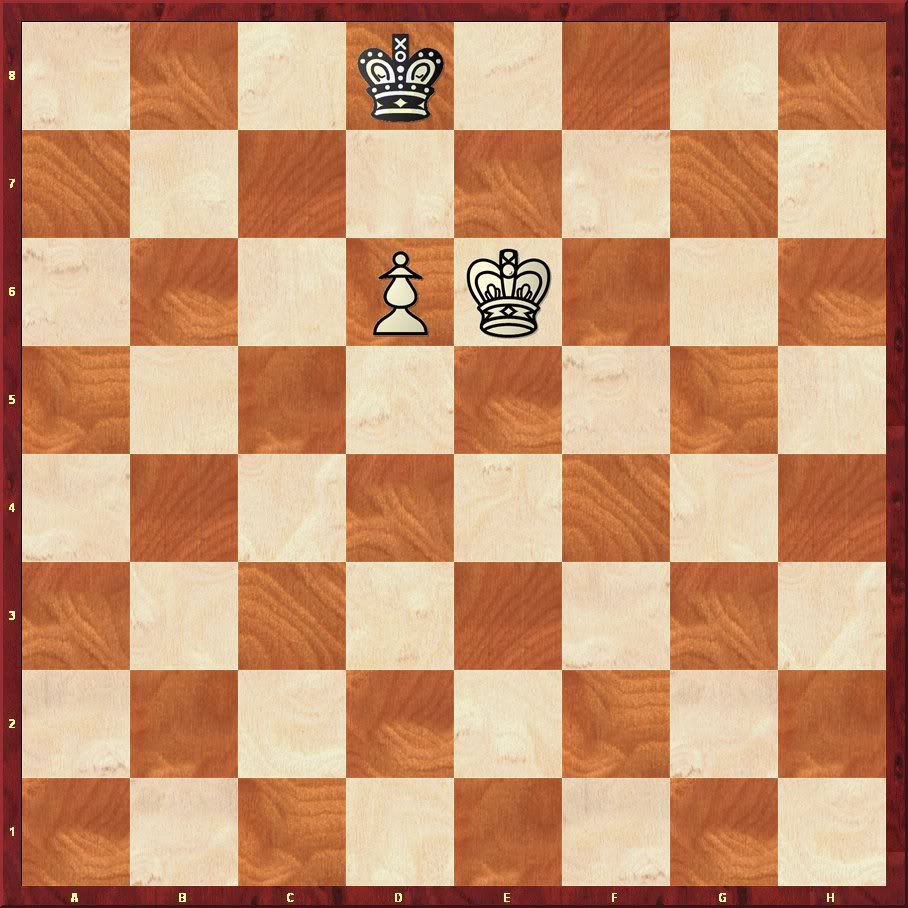

Black to move draws; White to move wins.

In the middlegame positions, the rationale for excluding the knowledge of who is on move differs. The authors offer a useful explanation at the head of a chapter containing 120 positions and fifty-nine game scores.

The first part of the chapter gives the positions. Certain of the games have more than one position included. These positions are like the fingerprint of the games—from this fingerprint, the associated game can be identified. Following the positions, the full game scores are given.If I study the games, if I make the effort to memorize them, then I know when I see the position whether Black or White is on move. Moreover, in some positions there might be some useful insights gained from an extra tempo. If the position derives from a game where White was on move, but we look at the diagram as if it is Black to move, the result might differ. Such a thought experiment could reinforce the need for vigorous play, for the element of time in chess strategy.

GM-RAM, 77

The Legendary 300

On the back cover of the book, the publisher offers an extract from the introduction.

In Russian folklore it is said that there are 300 positions which comprise the most important knowledge an aspiring player must acquire. About two-thirds of them are from the endgame and the remaining third are from the middlegame.In the introduction, Ziyatdinov explains that opinions differ as to the precise identity of these 300. He mentions Lev Alburt’s Chess Training Pocket Book: 300 Most Important Positions & Ideas (1997) which contains a substantially different collection than the 253 in GM-RAM (forty-seven are left to the reader). Ziyatdinov’s selection favors endgames and middlegame positions from the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Botvinnik-Tartakower, Nottingham 1936 is the most recent game in the fifty-nine. Alburt’s collection favors more recent grandmaster practice.

GM-RAM, 12

Ziyatdinov also offers a more ambitious assessment of the value of complete games from the nineteenth century.

If you know just one of the important classical games, you will be able to become a 1400 level player, know 10 games and you will be 2200 level, know 100 and you will be 2500.That’s it: my road to expert is much shorter than I thought. If I know ten nineteenth century games, I’ll blast right through expert and make master. But, wait, I’ve known more than ten of these games for years, and I only recently broke into class A. What holds me back from realizing Ziyatdinov’s promise?

GM-RAM, 77

My knowledge of such games as Anderssen’s “Evergreen Game” must lack depth. Ziyatdinov explains how infants acquire language, “when we start to speak, we repeat many times the words we are hearing from other people” (7). When he speaks of knowing a game, he does not mean the way I have memorized a handful of poems, or part of Ahab’s soliloquy in Moby-Dick (1851). Rather, he means learning those games the way we learn the alphabet, and the combinations of sounds that make up the words we use every day without needing to think about them. He likens this “tacit knowledge” to the information stored in a computer’s RAM. Possession of this knowledge renders playing second nature.

Alburt’s promise is more modest. His 300 includes twelve key king and pawn endgame positions, and claims these are all that are needed to become a strong player. On the other hand, a master must know fifty positions.

Here’s a promise: To be a strong player, you do not need to know hundreds of King and Pawn endgame positions—but only 12 key positions. Of course they have to be the right positions—and they’re in this book! To be a master you do not need to know thousands of King and Pawn endings. You need to know 50 key positions.While I was waiting for GM-RAM to arrive last week, I created forty-eight flash cards of pawn endings. These forty-eight are all of the blue diagrams in the first chapter of Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual (2003). The two dozen pawn endgames in GM-RAM: Essential Grandmaster Knowledge include a few that are not among these forty-eight, but perhaps all the essential ideas are in both sets. Knowing Ziyatdinov’s two dozen, and Dvoretsky’s four increases my number to about sixty pawn endgames. That’s not too intimidating.

Alburt, 9

Very Interesting! I have had the GM-RAM book on my short list for some time and inspired by another source, I decided the other day to try to memorize a few games.

ReplyDeleteThe pawn positions shown has all to do with the keysquares (on which the king has to stand for the pawn to promote) of the king. In your first example the pawn has past the 4th rank so its key squares are just in front of the pawn namely c6-d6-e6, so no matter who is to move the king will always land on such key square (for a pawn which has not yet crossed the middle of the board the keysquares are two rows ahead. So for example for a pawn on e3 the keysquares for the king are d5-e5-f5.

ReplyDeleteIf we see at the second example, with black to move white king can not go to a keysquare, Ke8 blocks that while if white to move white can play d7 which leaves only Kc7 for black after which white can play Ke7 and on the next move promote his pawn safely.

Offcourse, all the above goes not up for a the pawns on a- and h-file. Those have their own rules like not letting the black king enter the little box of b7-a7-q-a8-b8 for the a-pawn and g7-g8-h7-h8.

Let us know if you ever publish your flashcards!

ReplyDeleteI've never understood the lure of that book. Add a couple of comments on the positions, will it all become worthless with a little more effort from the author?

ReplyDeleteSomeone should put out an annotated version of that book :)

Blue Devil,

ReplyDeleteThe book is more a study system than a collection of positions. As for the positions, the endgame ones are easily found in Averbakh (available when the book was written) or Dvoretsky (which came out more recently). The middlegame positions all stem from the games provided in the text: it is an error to say there are no comments on the positions. Study the games themselves, and work out whether the best moves were played. That analysis is the training, and the evaluation of the positions.

James, I am wondering what you think of GM-Ram, now that you've had it for a few months. I have the chance to buy a copy but I'd like a few more opinions before taking the plunge.

ReplyDeleteAlastair

Alastair, I am training daily either with that book or with others via methods inspired partly by GM-RAM and partly by reading in the psychology of learning and excellence provoked by David Shenk's The Genius in All of Us. It is the most important chess book I have acquired in 2010.

ReplyDeleteWhen it first arrived, I started working through each of its sections: endgames, tactics, the games from which the tactics positions were derived. After about two months, other elements of my life and work necessitated a reduction in time spent on chess training. In the past week, my chess training time is becoming available again, and the first study I turned to were the first several games (Anderssen's) in GM-RAM.

I just found a $35 dollar copy used on Amazon.com - rare book but will enjoy it I'm sure

ReplyDeleteI just bought the book for 2.10 dollars in India,a great find from a second-hand bookshop.I think the study method needed to get any benefit from the book makes the book outstanding.As GM Nigel Davies said you do not improve by reading chess books and nodding your head.

ReplyDeleteIn your first position, white to move draws. If the pawn were one square back, white would win in any case.

ReplyDeleteAnon,

DeleteThe key line in the first diagram: 1.Ke6 Ke8 2.d6 Kd8 3.d7 Kc7 4.Ke7

Nevermind -- that is not the case, of course, when the weaker king is on the back rank.

ReplyDeleteGlad that you worked it out!

DeleteJames, this whole business of memorizing games is very intriguing to me. I've always put off memorizing games, because there is actually quite a bit of neuroscience that contradicts any suggestion that building blocks from a few particular games could be widely applicable and helpful. In neuroscience, it is understood that the process of the mind's abstraction (i.e., generation of an abstract pattern that is widely applicable over particulars) requires exposure to numerous particular instances which vary somewhat. Despite this, I've been memorizing some games from Zurich '53, NY '24, and "My Great Predecessors," and I'm shocked to find myself recalling variations of tactics from within those memorized games. It's basically inexplicable within the ambit of all the science I know. Have you experienced any extraordinary results from memorizing the GM-RAM games, so far as you can tell? I'm planning on memorizing the games in the book. I figure that, if the games are any more essential than the anthologies from which I am currently memorizing, the surely I'll gain much more in the way of benefit.

ReplyDelete