Meanwhile, I'm collecting middlegame positions. I have several sets of cards that I created years ago. The oldest are index cards upon which I stamped diagrams, and laboriously stamped each piece with red or blue ink on the appropriate square. When I look at these old cards, I am reminded of time I spent reviewing them between rounds at the Dave Collyer Memorial tournament the last time Gary Younker ran it. Gary died in 2001, and shortly after his death we created a foundation to honor his memory and continue his work. The 2001 Collyer was a good event for me. I started the event rated 1400 and had an even score against three B Class opponents. My run of success started late Saturday night when I discovered a practical chance in this hopeless position.

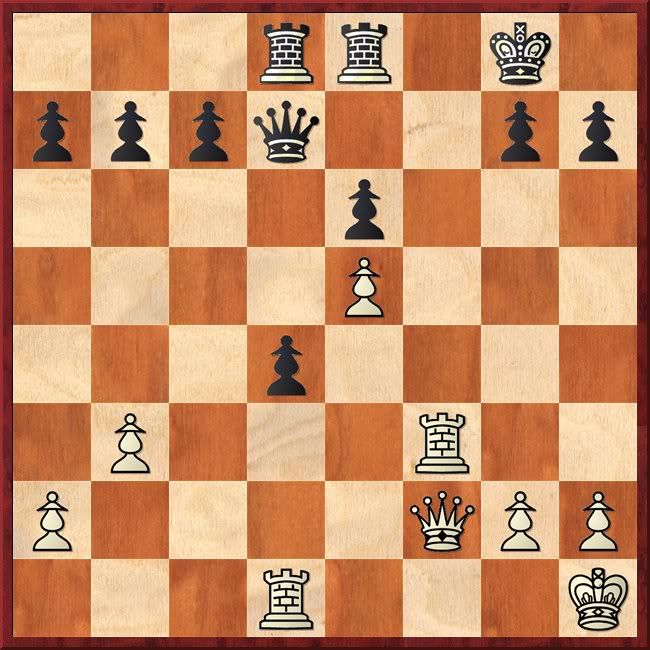

White to move

I'm down two pawns, and there's no stopping my opponent's d-pawn. In a final desperate ploy, I played 31.Rf1! Keith Brownlee had several ways to counter my threat, but instead played 31...d3?? I sacked a rook to force a draw by repetition. After the game, my opponent told me that he only examined my checkmate threats, of which there were none, but not my drawing combination. He also stated that this game was the first time he failed to win against the King's Gambit.

On Sunday morning I beat a B Class player in a game that summoned more tactical courage from me than was my custom. Flash cards contributed to my confidence. Within the next year, I bought some software that facilitated creating professional looking printable diagrams, and my index card collection went into storage. I collected dozens of positions from Lazlo Polgar's Chess in 5334 Positions (1994) and several databases. I printed these positions on cards with a diagram on one side and the best moves on the other.

My initial non-provisional USCF rating was in the low 1400s, but before it was published I played in an event that pushed it up to 1495. That was in 1996, but in 2000 I was back down to 1400. My success in the 2001 Collyer rocketed me up to 1450, and in 2002 I climbed over 1500. I faltered briefly in 2004, dropping to 1487 before rising to 1600 in 2005. I made it over 1700 for the second time in 2008, and kept climbing over 1800 in 2009. If I am to cross over 1900 in 2010, my training must step up a notch.

Ziyatdinov's Method

Rashid Ziyatdinov advocates learning entire games thoroughly. In GM-RAM: Essential Grandmaster Knowledge (2000), he lays out a plan for improvement based on 300 key positions. Half of these are endgame positions--most are pawn endgames and rook endgames--and the others stem from classic games. His fifty-nine games from which the middlegame positions arise span less than a century from a few 1851 victories of Adolph Anderssen to Mikhail Botvinnik's 1936 defeat of Saviely Tartakower.

I find myself drawn to certain aspects of Ziyatdinov's method. My cards from Dvoretsky's text lack the answers on the back, for example. I'm also working on memorizing games, including those in Ziyatdinov's fifty-nine. His most compelling idea is the notion that key diagrams function as fingerprints of whole games. Most collections of diagrams highlight tactical motifs. There are certainly quite a few tactical shots in Ziyatdinov's collection. But memorizing, studying, and knowing thoroughly a limited set of games--the plans that led to what happened over the board, and what might have happened--goes beyond tactical patterns. The 120 middlegame positions in GM-RAM "are like the fingerprint of the games--from this fingerprint, the associated game can be identified" (77).

Karpov's Best Games

Although I share with Ziyatdinov the conviction that nineteenth and early twentieth century games merit our attention, I am unwilling to limit my study to these old games. I may end up with more than the legendary 300 positions as I pursue Ziyatdinov's regimen (he expects the reader to supply nearly four dozen of the 300). As I am going through the best one hundred games of Anatoly Karpov that were published in Chess Informant (see "Coincidence?"), I am collecting diagrams. These diagrams are fingerprints for games worth knowing as thoroughly as Anderssen's "Evergreen Game".

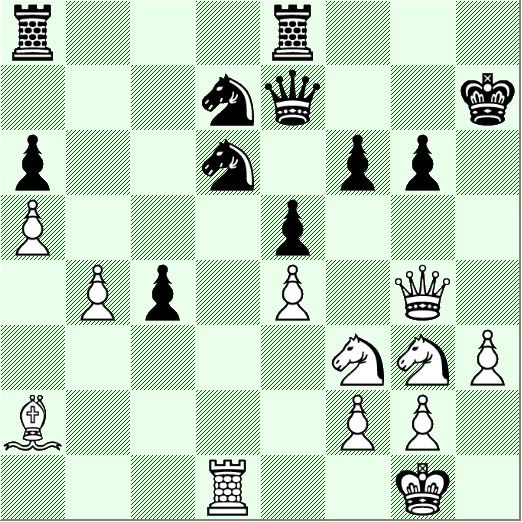

Some of the positions from Karpov's games feature tactical shots. In this position from 1973, Karpov's tactical shot provoked Spassky's resignation.

White to move

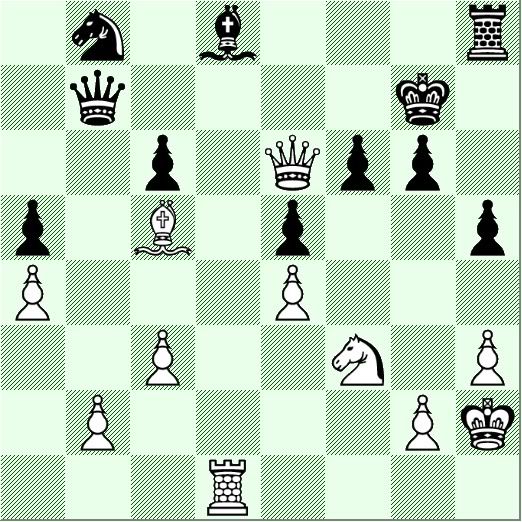

The following year, in the ninth game of the World Championship Candidate's Match, another tactical shot by Karpov provoked another resignation by Spassky.

White to move

Then, in 1977 at Las Palmas, A. Martin Gonzalez perceived the futility of further resistance when Karpov's move threatened a clever mating net.

White to move

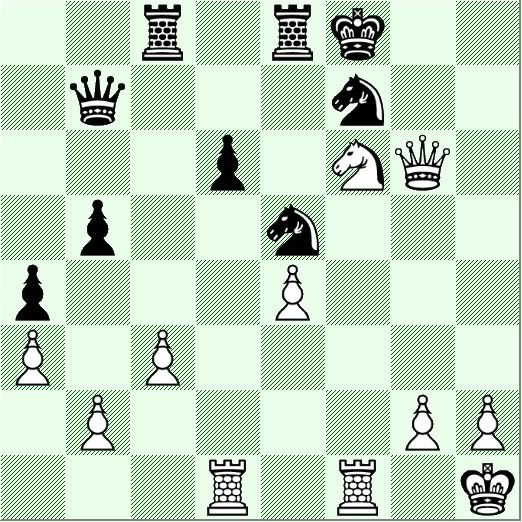

Such tactical shots are the bread and butter of chess training. But, it seems to me that if I can comprehend the thought processes that went into finding the move that Karpov played against Vlastimil Hort from this position in 1971, it might become part of the knowledge that can elevate me to expert class.

White to move

Hort played on for another eleven moves as Karpov increased the pressure. This diagram is the fingerprint of the earliest of Chess Informant's list of Karpov's 100 best. It is a positional masterpiece, Karpov's signature. As I collect these diagrams, I aim to learn the games from which they stem.

No comments:

Post a Comment