Kon Grivainis explained his strategy while playing in the World Correspondence Chess Federation's championship without the access to the latest theory that was available to his opponents:

Due to my travels I had discarded all my opening books. I did not have any. ... I had to find obscure variations! Remember Fischer--he used to do that to get away from the Russian research.He adopted the Trompowski Attack as part of his strategy to avoid the deep study of trendy opening manuals.

Grivainis, Winning Correspondence Chess (1997), 70.

My first taste of correspondence play began with friends in the 1970s, and I entered one USCF tournament. My "extensive" chess library consisted of some one dozen books, including I.A. Horowitz, Chess Openings: Theory and Practice (1970). As college brought new activities into my life, chess play all but ceased. I returned to active chess after finishing graduate school, and entered some correspondence events in the late-1990s. It was then that I bought my first issues of Chess Informant, and the first two volumes of the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings.

One game that I played in the late 1990s became memorable because my research took me to one specific game in Chess Informant 64. My game had the same position as the reference game for a single move, but studying Chess Informant suggested an idea that carried me through to victory. Of course, notes in the printed copy of this volume, and in the margins of my printed ECO confirm that I looked at a great many games with similar ECO codes. In addition to CI and ECO, I had a copy of Zoltan Ribli and Gabor Kallai, Winning with the English (1992). The Informant reference game was a win by Ribli in the 1995 Hungarian Championship.

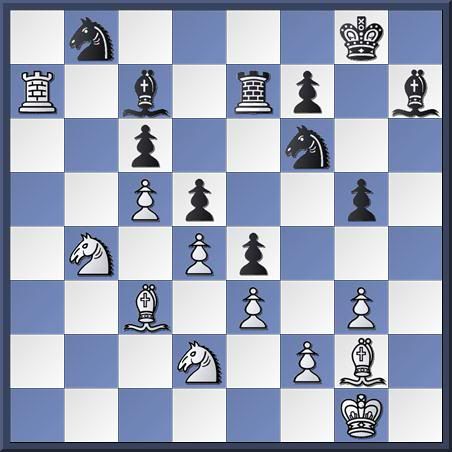

Ribli,Z - Sherzer,A [A12]

Magyarorszag 64/7, 1995

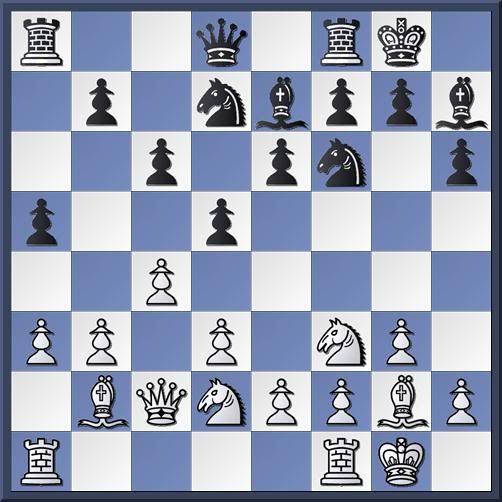

1.Nf3 Nf6 2.g3 d5 3.Bg2 Bf5 4.d3 e6 5.0–0 Be7 6.c4 c6 7.b3 0–0 8.Bb2 Nbd7 9.Nbd2 a5 10.a3 h6 11.Qc2 Bh7 12.Bc3 b5 13.cxb5 cxb5 14.Qb2 Qb6 15.b4 axb4 16.axb4 Rfc8 17.Rxa8 Rxa8 18.Nb3 Bd6 19.Ra1 Re8 20.Bd4 Qb8 21.Bc5 e5 22.Ra6 Nxc5 23.bxc5 Bc7 24.d4 e4 25.Ne5 Bxe5 26.dxe5 Nd7 27.Qd4 Nxe5 28.Qxd5 Nc4 29.Bh3 e3 30.f3 Rd8 31.Bd7 Qc7 32.Ra8 Bc2 33.Bf5 1–0

My opponent was Faneuil Adams, Jr., one of America's premier chess patrons. The game was played the two years prior to his death. We began early in 1997, and he resigned in November 1998. During the game we carried on a bit of conversation concerning scholastic chess on our move cards--I was a single father of a young boy who began showing an interest in chess at age four, and Adams helped found New York's Chess-in-the-Schools program. I remember the conversation as much as the game. It was a privilege to play this distinguished opponent.

Stripes,James - Adams,Faneuil [A12]

97 CA 17 USCF Class, 1998

1.c4 c6 2.Nf3 d5 3.b3 Bf5 4.g3 Nf6 5.Bg2 e6 6.Bb2 Nbd7 7.0–0 h6 8.d3 Be7 9.Nbd2 0–0 10.Qc2 Bh7 11.a3 a5

Through an entirely different move order, we have reached the same position as Ribli-Sherzer 1995 that I found in Informant 64/7.

12.Bc3!

Copying Ribli. Studying Ribli's game suggested reasons for this move: supporting b3-b4, and vacating b2 for the queen. From b2, the queen asserts her influence along the long diagonal and supports action along the a- and b-files. The flexibility of these two-pronged assaults and their facilitation by the quiet Bc3 was outside the scope of how I had been thinking about chess strategy prior to this game.

12... Qb8

12...b5 was played by Sherzer

13.b4 axb4 14.axb4 Rxa1 15.Rxa1

15.Bxa1? Bxb4 16.Rb1 c5 gives Black an edge.

15...e5 16.e3 Re8

17.Qb2

White prepares the advance b5.

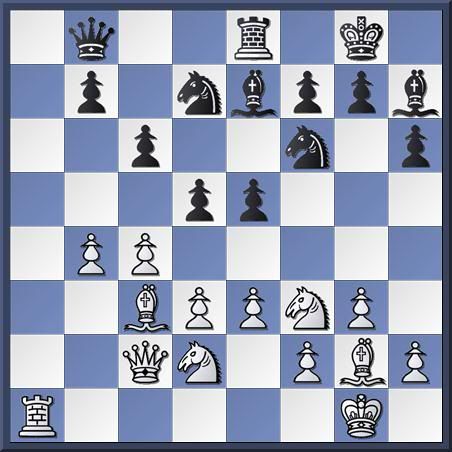

17...Bd6

Black plans e4.

18.c5 Bc7 19.d4 e4 20.Ne1

20... h5

One of the small errors: failing to interfere with White's plan. 20...b5 21.Qa3 would have left White with a very slight edge.

21.b5 g5

Rybka prefers 21...Bf5 22.Nc2.

22.Nc2± h4

Another slight error.

22...Bd8!?±

23.bxc6+- bxc6

24.Qxb8

I might have built up pressure more effectively with 24.Nb4 Qb7 25.Ra6 Kg7 26.Rxc6 Rd8+-.

24...Nxb8± 25.Ra7 Re7 26.Nb4 hxg3 27.hxg3

27...g4?

One of only two moves given a question mark by Rybka 4 full analysis. It's an ugly move that reduces the mobility of Black's light-squared bishop. Such dynamic positional concepts within the algorithms of chess software, it seems to me, contributes in large measure to the current strength of Rybka, Hiarcs, Fritz, and other leading engines.

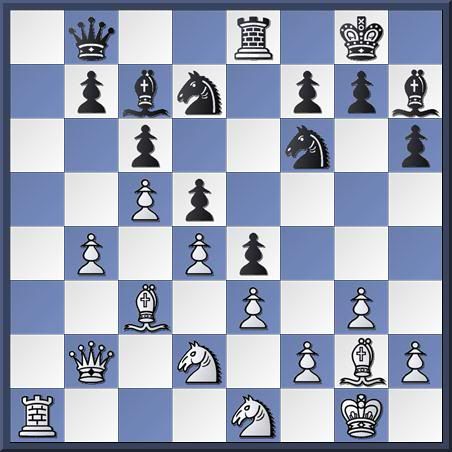

27...Bf5!? and Black is still in the game

28.Na6+- Nxa6 29.Rxa6 Re6 30.Nb3 Nh5?

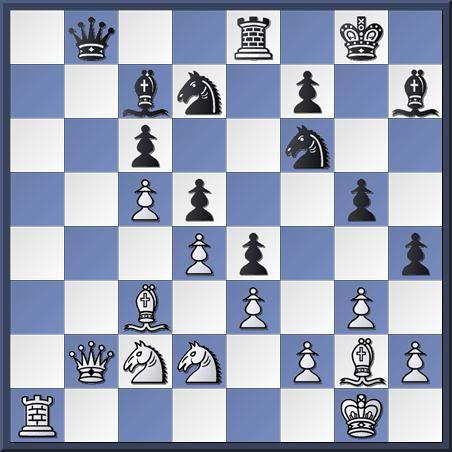

The other move that Rybka deemed an error. But, the superior 30...Ne8+- does not change the game's evaluation. It is clear that White's penetration on the queenside will roll up Black's defenses. What can Black do to generate some play? My opponent seized on the idea of sacking a piece for two pawns, perhaps creating a vulnerability for my king.

31.Ba5 Bxg3 32.fxg3 Nxg3 33.Bc7 Nf5 34.Be5 f6 35.Ra8+ Kg7 36.Ra7+ Kg6 37.Bf4 Bg8 38.Bf1 Bf7 39.Ba6 1–0

Nice game!

ReplyDeleteYou finding that game was probably a big help in playing this game. Always nice to have a GM game to guide you.