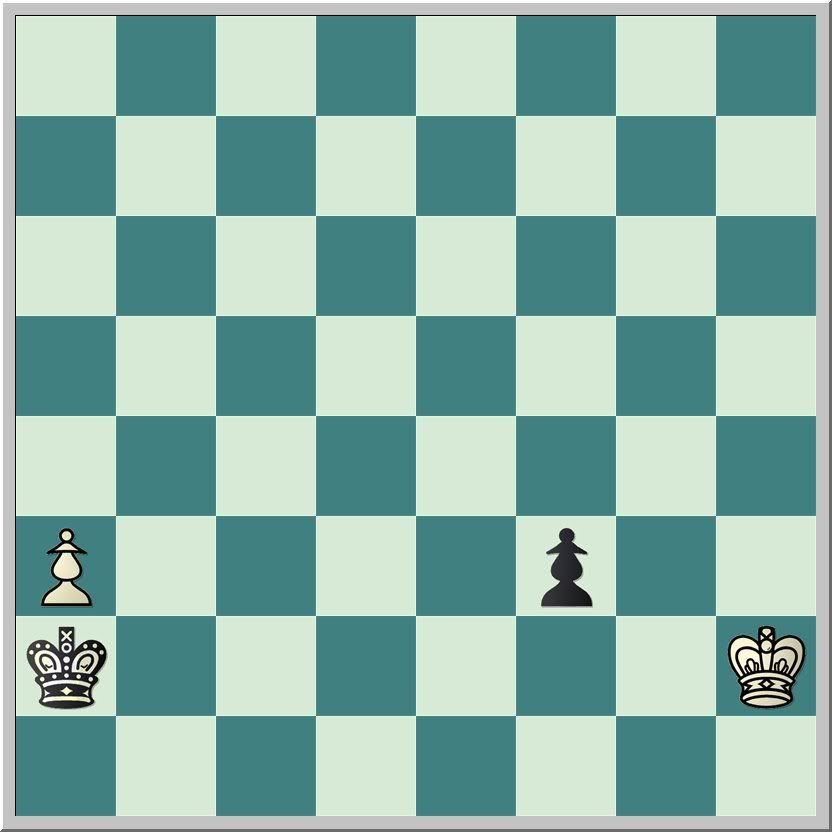

Rinck 1922

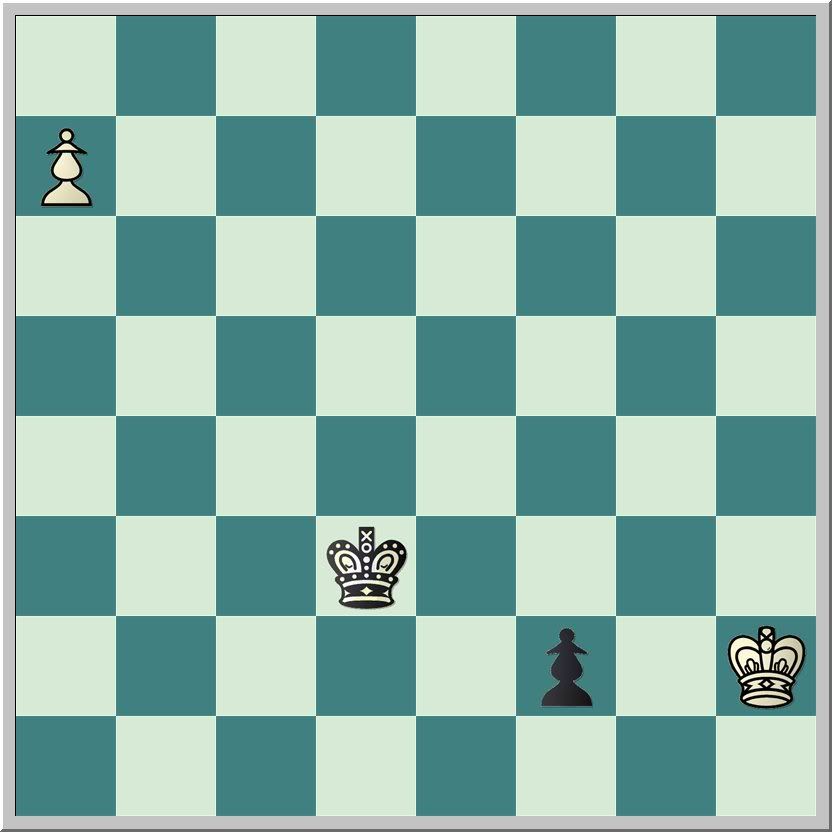

Of course the king cannot catch the pawn. This one is too easy.

1.a4 Kb3 2.a5 Kc3 3.a6??

Black to move =

3...Kd2

Something went wrong. Both players will promote and reach a drawn queen endgame.

White needed to play 3.Kg1

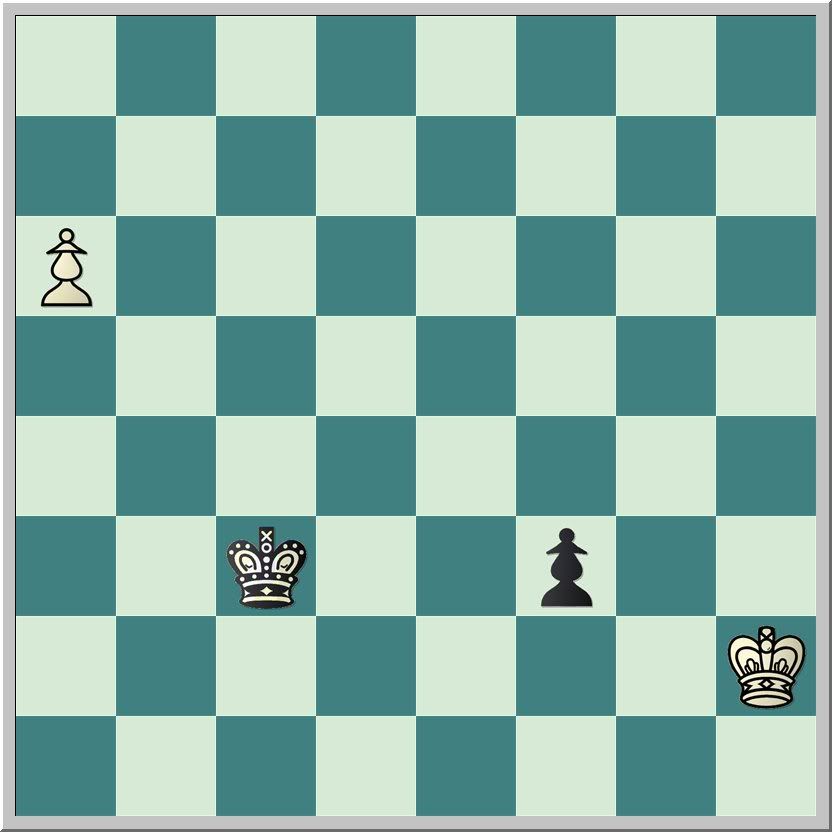

Drawing Resource

Black's defensive strategy in Henri Rinck's 1922 composition employs the idea from a study by Richard Reti from the previous year.

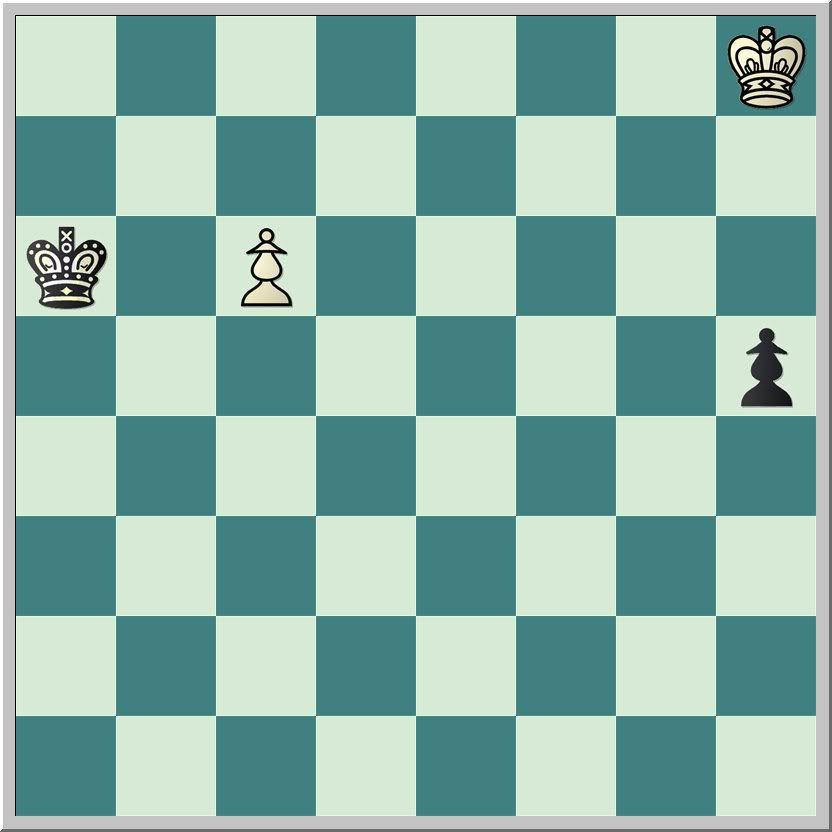

White to move =

Reti 1921

The White king can catch the Black pawn because of the strange geometry of the chess board. The shortest distance is not a straight line. The king's route h8-g7-f6-e5 combines the threat of supporting the c-pawn with the chase of Black's h-pawn. Either both players queen, or both pawns fall.

Rinck's 1922 study, which appears as #53 in Laszlo Polgar, Chess Endgames (1999), is not as simple as it looks. The first move is easy: the pawn must run. But from the diagram position, the solver must calculate the point at which the king must move to stop Black's drawing threats. Move three is critical. If Black tries 2...Kc3, White must play 3.Kg1. If Black tries 2...Kc4, White must play 3.a6.

After 1.a4 Kb3 2.a5 Kc4 3.a6 Kd3 4.a7 f2! Black also promotes and more calculation is needed.

If Black promotes to a queen, White wins the queen with a skewer. This line is the one given in Polgar's solution. Hiarcs 12 promoted with check: the pawn became a knight. Its tablebases revealed that queen promotion led to checkmate in eleven, while underpromotion to the knight was checkmate in eighteen.

After the underpromotion, White still has some work. A human under time pressure can easily falter and permit a devastating fork, Black's final drawing resource.

No comments:

Post a Comment