A weakness is a defect in one's position. It can take the form of a pawn, a square, a file or a diagonal. A weakness is of a permanent nature.At some point during my Sunday morning game in the Eastern Washington Open, I recalled the effect upon my play of reading, several years ago, Jacob Aagaard's Excelling at Technical Chess (2004). This book helped cultivate my resistance to offering or accepting draws when there is an imbalance in the position, whether the imbalance concerns pawn structure, material differences, or clear initiative. If more than one of these is present, and one player has two weaknesses, the chances are great that the other should be playing for a win.

Jacob Aagaard, Excelling at Technical Chess

My game featured a long endgame in which I had one pawn more than my opponent, pawns were on both sides of the board, and I had a bishop versus a knight. The first draw offer by my opponent was a reasonable effort on his part to get out of a jamb. I recorded "DO" on my scoresheet, and made my move, signaling my refusal. His second draw offer irritated me. After the third offer, I scolded him with a threat of complaining to the TD, who could impose a time penalty. Two moves after the third offer, I blundered. Although my practical winning chances remained strong, especially as my opponent now had less than one minute remaining on the clock, I had let the technical win slip away.

I went through the game, entering my comments and evaluations. After doing so, I checked my evaluations with Rybka 4. Only then, did I discover the critical error in my endgame play.

Stripes,James (1824) - Joshi,Kairav (1886) [D02]

Eastern Washington Open Spokane (4), 02.10.2011

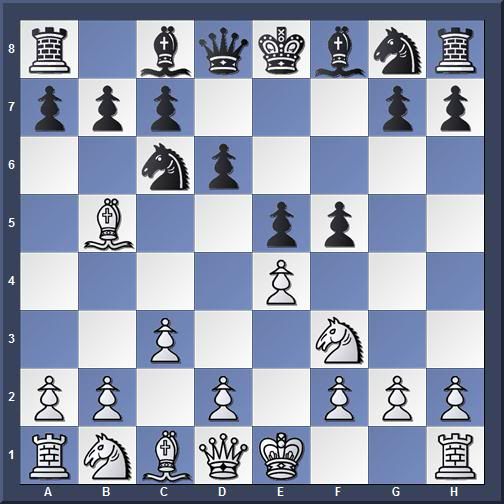

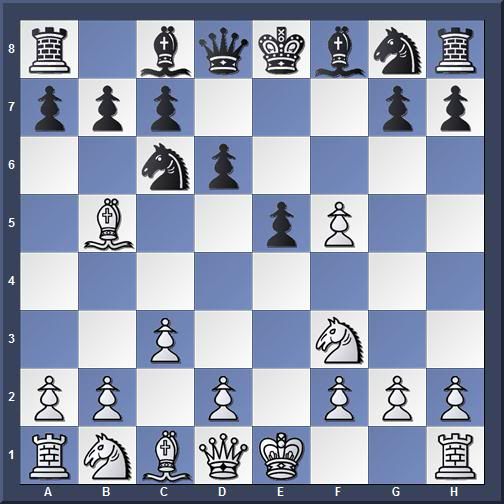

1.Nf3 c5 2.g3 Nf6 3.Bg2 d5 4.d4 cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.c4 e6 8.0–0 Be7 9.Nc3 Bb7 10.Bf4 0–0 11.Qb3 Ba6 12.cxd5 cxd5 13.Qa4

Black to move

I felt that I'd gained something from the opening: queenside pawn majority, bishops aiming at the queenside, rooks connected and ready to come to the open c-file and the half-open d-file. I would like to swap pieces and go into a pawn endgame. Trading my e-pawn for Black's d-pawn, or provoking the d-pawn to advance where it becomes weak are considerations. I have a comfortable game and a slight advantage with long-term chances for a better endgame.

13...Bb7 14.Rfd1 Qb6 15.Qb5N

Using the novelty annotation feature of Chess Base 11 brings up this game for comparison: 15.Be3 Qa6 16.Rac1 Rfc8 17.Qxa6 Bxa6 18.Bf3 Nd7 19.Bf4 g5 20.Be3 Ne5 21.Bg2 Nc4 22.Bd4 Bb7 23.b3 Nd6 24.Be5 f6 25.Bxd6 Bxd6 26.Nb5 Bc5 27.e3 a6 28.Nd4 Kf7 29.Bh3 Bxd4 30.exd4 Rxc1 31.Rxc1 Rc8 32.Rxc8 Bxc8 33.Kf1 Ke7 34.Ke2 Kd6 35.Kd3 a5 36.Kc3 Ba6 37.Bg4 h6 38.Bd1 e5 39.Bc2 e4 40.b4 axb4+ 41.Kxb4 f5 42.Kc3 f4 43.Kd2 Kc6 44.a3 h5 Eckhardt,C (2260)-Ozturk,K (2034)/Kusadasi 2006/CBM 111 ext/1–0

Is this game score complete and correct? The position appears even. Surely Black did not resign in such a position.

15...Bc5 16.Qxb6 Bxb6

As my opponent and I discussed in the postmortem, 16...axb6 seems better, activating the queen's rook.

17.Rac1 Ng4!

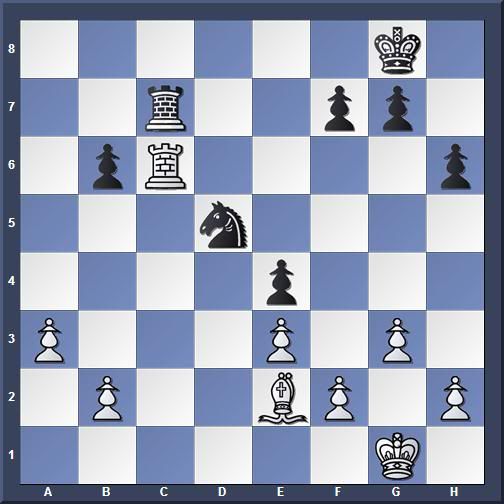

White to move

I had used eighteen minutes getting to this position, and now thought for seven minutes--my second longest think of the game. This was the only time in the game when Joshi's superior tactical skills were a significant factor in the game. I decided almost immediately upon the correct move, but realizing that my bishop would become trapped, had to find a compensating resource. It appeared to my opponent that this resource was more than adequate, and as a consequence, he opted to let my bishop escape. I added "to my opponent" to the previous sentence after going through the variations with Rybka, although during play I was far from certain that my resources were sufficient to secure the decisive advantage that I thought was just within reach.

18.e3

Rybka prefers 18.Rf1. In other words, my "correct move" was probably incorrect.

18...e5 19.Bg5 h6

The critical line that had me concerned after Black's move 17 begins with 19...f6! I planned to play 20.Bh4 in order to avoid opening the f-file, but also intended to go into another long think here. I believed that allowing Black counterplay along the f-file would neutralize my advantages elsewhere.

Rybka denounces 20.Bh4 in favor of 20.Nxd5 fxg5 21.Nxb6 (21.Ne7+ is no good 21...Kh8 22.Bxb7 Nxf2 with advantage for Black) 21...Bxg2 22.Nxa8 Bxa8 23.Rd2=.

After 20.Bh4, Black might proceed 20...g5, leading to clear advantage for White after 21.Nxd5 gxh4 22.Nxb6 Bxg2 23.Nxa8 Bxa8 24.Rd7. But, perhaps 20...g5 is not Black's best option. In any case, Black's 19...h6 was a relief.

20.Be7 Rfe8 21.Nxd5

At this point, having won the d-pawn, I become confident that my winning chances are very good.

21...Bxd5 22.Bxd5 Rab8 23.Bd6 Rbd8 24.Bc7

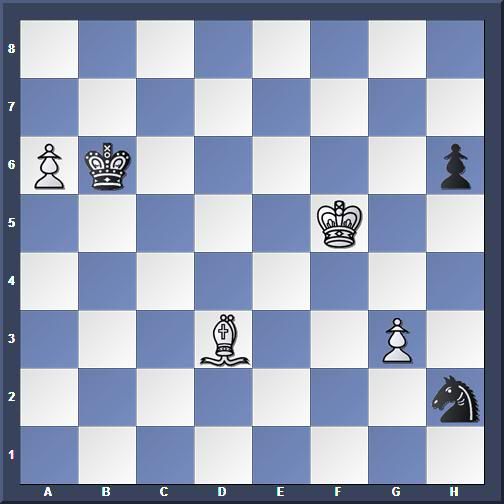

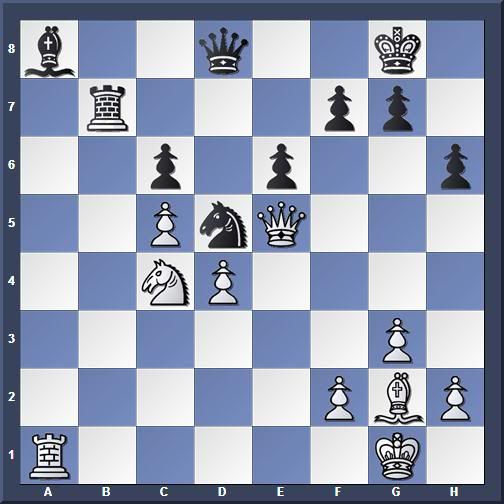

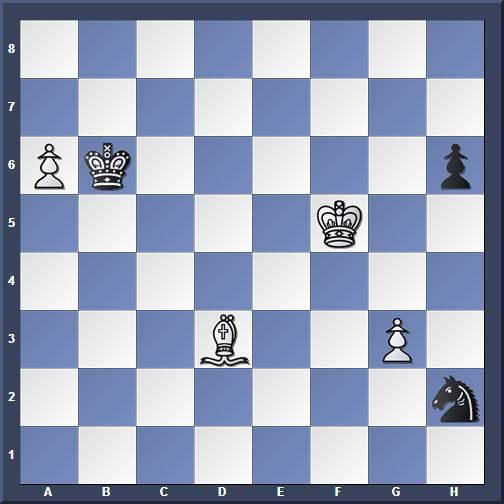

Black to move

I believe that I have a technical win. But there is much play ahead to demonstrate this advantage. I went on to win against my A-Class opponent, but this position merits practice against the engines. If it is indeed a technical win, can I win against Rybka? Houdini? Hiarcs? Fritz?

24...Rc8 25.Bxb6 axb6 26.Bc6 Re7 27.Bf3 Rxc1 28.Rxc1 Nf6 29.Rc6 e4 30.Be2 Nd5 31.a3 Rc7

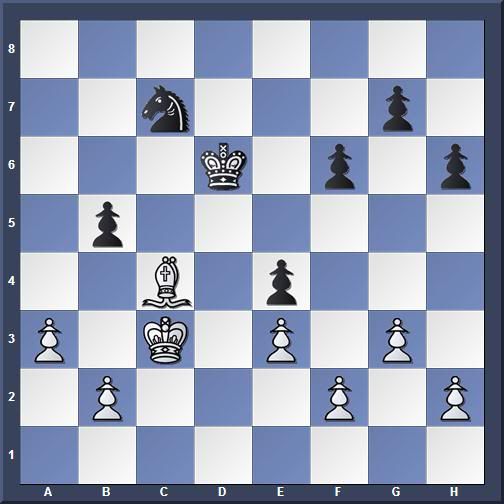

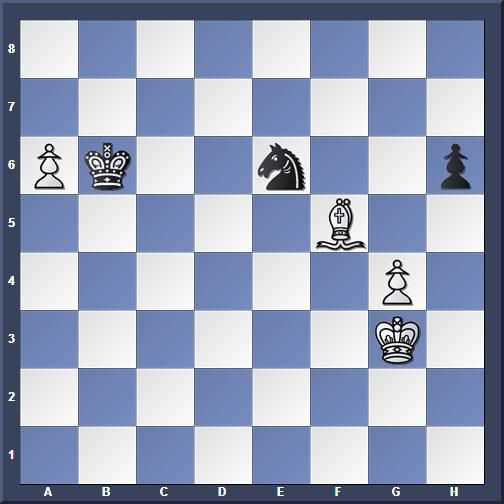

White to move

32.Rxc7

32.Re6 is less good. A bishop versus a knight with pawns on both sides and a majority on the queenside is a technical win.

32...Rc5 33.b4 Rc1+ 34.Kg2 Nc3 35.Ba6

32...Rc1+ 33.Kg2 Rb1 34.Rxd5 Rxb2

32...Rc2 33.Rxd5 Rxe2 34.Rb5

32...Nxc7

Now I am certain that I have a technical win, and the plan is straight-forward. The majority must be converted into a passed pawn, tying down one of Black's pieces. Then with two active pieces to one, White shifts attention to the kingside in order to create another passed pawn.

33.Kf1

First, the kings race to the action.

33...Kf8 34.Ke1 Ke7 35.Kd2 Kd6 36.Bc4

attacking a vulnerability

36...f6

36...f5 gives the bishop a target

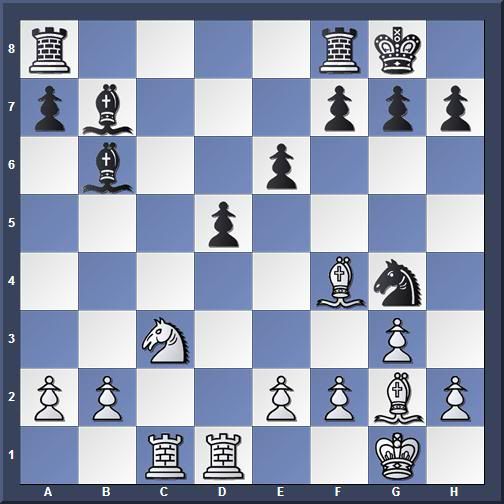

37.Kc3 b5

This move seems tactically necessary, but White wants Black's pawns on light squares.

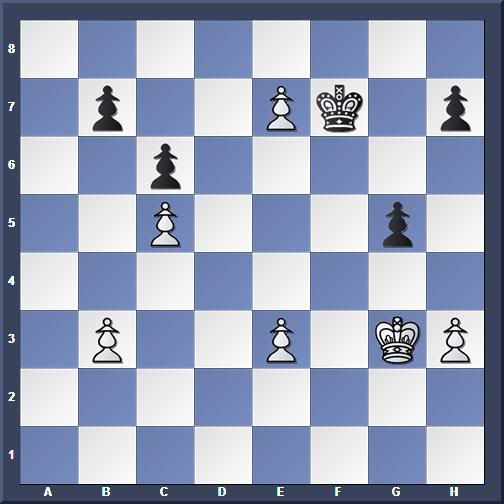

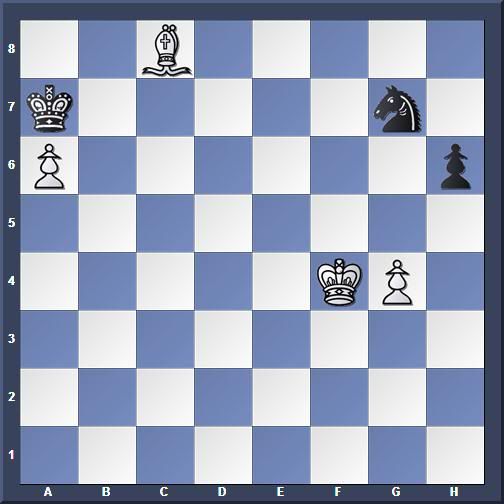

White to move

38.Bf7

Observe the bishop's ability to restrict the knight. White is happy to trade minor pieces because the pawn endgame is a simple win.

38...Na6! 39.Kd4 Nc5

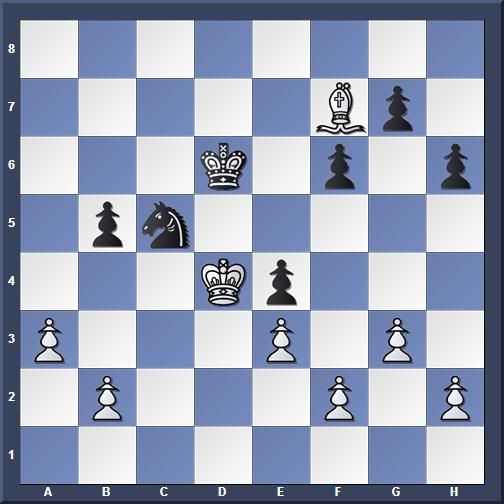

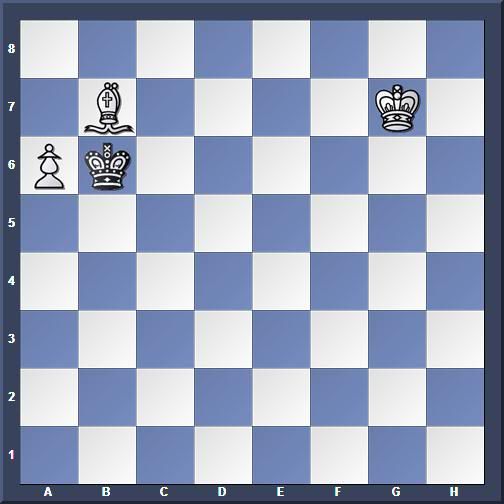

White to move

Now my longest think of the game: eight minutes. I will lose the f-pawn, and possibly the b-pawn, but will pick up the b-pawn and e-pawn in exchange.

40.Be8 Nd3 41.Kxe4 Nxf2+ 42.Kf3 Nd1 43.Bxb5 Nxb2 44.Ke4 Nd1 45.Kd4 f5 46.a4 Nf2 47.Be2

Black to move

Protecting the h-pawn

47...Ne4 48.a5 g6 49.a6 Kc7

Black's king becomes inactive. The white bishop, although tied to defense of the passed pawn, is nevertheless able to move about restricting the knight. Trading minor pieces remains a possibility because White's king is centralized and able to move over and gobble all the Black pawns before Black's king can return to the action.

50.Ke5 Kb6 51.Ke6 Nc3 52.Bd3 Nd1 53.Kf6 Nxe3 54.Kxg6 Ng4 55.Kxf5

Now, I can give up the h-pawn.

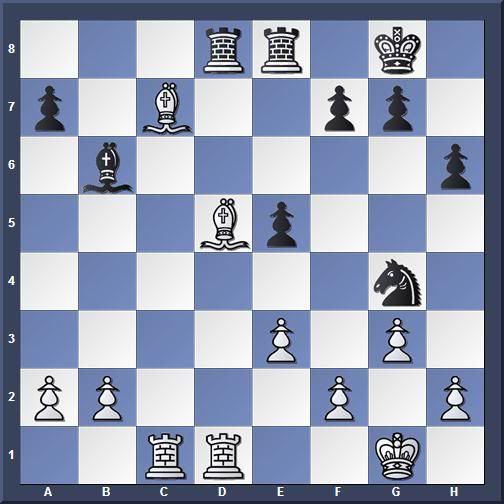

55...Nxh2

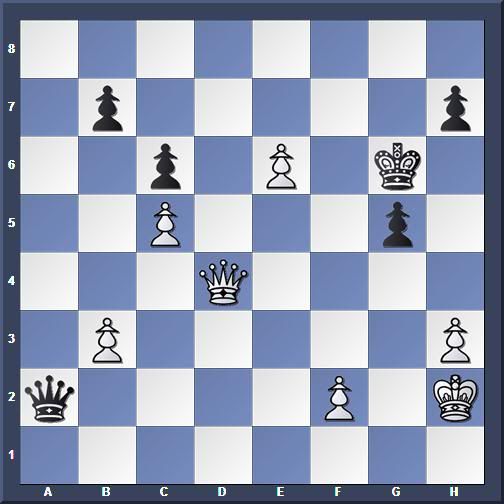

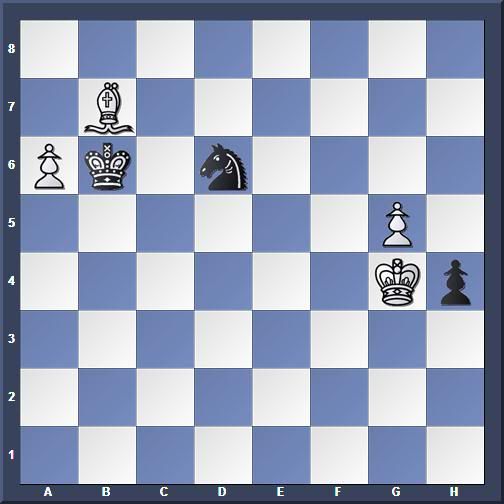

White to move

56.g4??

My plan is to eliminate Black's last pawn and force the knight to trade itself for my g-pawn. The rest will be easy. This plan came to fruition, but my opponent found some complications. He might have found a fortress after this error, but had less than one minute on his clock. I had forty-seven minutes remaining at this point. I have traded the technical win for practical winning chances.

56.Be2 was the correct move, trapping the horse.

56...Nf3 57.Kf4 Nd4 58.Kg3 Ne6 59.Bf5

I wanted to transfer the bishop to b7. This plan reduces the bishop's flexibility, but also reduces its vulnerability. It can be captured, but at the cost of the knight. The remaining pawn game on the kingside is easily won.

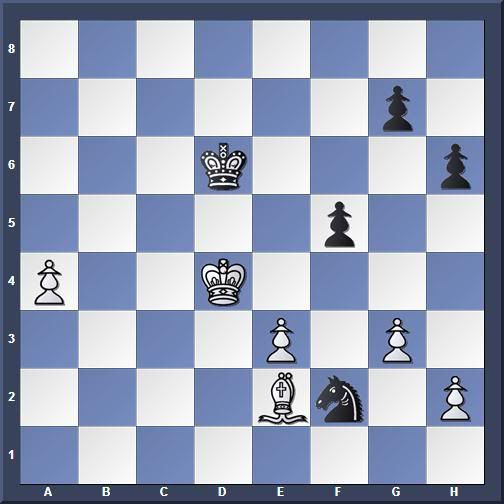

Black to move

59...Ng7

59...Nc5 makes things more difficult for White 60.Bc8 Ka7 61.Kh4 Nd3 62.Kg3 Nc5 63.Kf4 Nd3+ 64.Kf5 Nf2 and White is making no progress.

60.Bc8 Ka7

60...Ne8 makes White's job difficult 61.Kf4 Nd6 62.Bb7 Nc4

61.Kf4

Black to move

Again I have a clear win, and not only because my opponent is down to a few seconds.

61...Kb6 62.Ke5 h5! 63.g5

I gave this move a box.

Rybka sees a second alternative: 63.a7 Kxa7 64.g5 Kb8 65.Bh3 h4 66.g6 Kc7 67.Kf6 Nh5+ 68.Ke7 Kc6 69.Bg4 Nf4 70.g7+-

63...h4 64.Kf4 Ne8 65.Kg4 Nd6 66.Bb7

Black to move

66...h3

66...Nxb7 67.axb7 Kxb7 68.Kxh4 Kc7 69.Kh5 Kd7 70.Kh6 Ke7 71.Kh7+-

67.Kxh3 Kc7

67...Nxb7 68.axb7 Kxb7 69.Kh4 Kc7 70.Kh5 Kd7 71.Kh6 Ke7 72.Kh7+-

68.Kh4 Nb5 69.g6 Nd6 70.Kh5 Ne8 71.Kh6 Kb6 72.g7 Nxg7 73.Kxg7

Black to move

The rest is elementary.

73...Kc7 74.Kf7 Kb6 75.Ke7 Ka7 76.Kd6 Kb6 77.Kd5 Ka7 78.Kc5 Kb8 79.Be4 Ka7 80.Kb5 Kb8 1–0