Computers have "solved chess" when six or fewer pieces remain, and they are hard at work on the seven piece, which might be completed in the next few years. Eight and nine piece solutions are years away, and solving the game from the opening move remains a theoretical pipe dream. Three and four piece tablebases have been included with Fritz software for quite some time, and I believe the five piece are part of the package now. My old notebook computer that I bought in 2001 lacks the five piece because its 20 GB hard drive cannot provide the slightly more than 7 GB of free space that is required. In contrast, 30 MB are sufficient storage space for all three and four piece endings.

Each piece dramatically increases the space needed. The six piece tablebases exceed the capacity of most home computers, as they require an estimated 1.2 terabytes of storage space (see David Kirkby's discussion at ChessDB). When computers finally manage to work out the seven piece endings, how much space will be needed to store the data?

Now, consider the beginning of the game when there are thirty-two pieces on the board. After one move--White and Black--there are four hundred possible positions that can be reached. White can lose by checkmate on the second move eight ways, and can deliver checkmate on the third via 347 unique sequences. By the end of the fourth move (eight plies), there are 84,998,978,956 possible move sequences. Let's round the number to eighty-five billion.

Billions. Millions, and the Right Move

Of these eighty-five billion possible moves, the vast majority must be rejected immediately. The beginning player might need to look at quite a few--that's why chess seems so difficult to those first learning the game. This process is much quicker once the principles of center control and mobilization become second nature. Even so, the largest databases of previously played games top out under five million: Mega Database 2009 exceeds four million. How can a practical player reduce this mass of data to something useful?

There are many strategies for using databases to aid one's play. I do not always use the same methods, nor do I care to reveal all my secrets to potential opponents. Nevertheless, in the interests of eliciting some discussion, I'll explain how I approached one particular game that I played several months ago. This game was part of a team challenge, and I had a history with my opponent. We had played six games prior to the two we played in 2008, and I was down by two. I wanted to even the score.

Stripes - Adversary [C30]

Team challenge, 26.07.2008

1.e4!?

I tend to prefer queen's pawn openings in important games.

1...e5 2.f4 Bc5

We're already off the beaten paths. I seem to recall that I started using an opening book at this point. I've created several specialized opening books. I call one of these Master Trends. To create it, I first searched my largest database for games played in the past five years in which both players were rated 2200 or higher. These games were then saved into a new database. I found and deleted draws that were twenty moves or less. Then I created a new opening book in ChessBase. The database Master Trends was imported into the opening book, and while the computer did its work, I read a good novel--processing this data takes some time even with a fast computer.

In ChessBase or Fritz I can now open a book window and select the book I've named MT. Three moves present themselves:

3.Nf3

3.Nc3

3.Qh5

3.Qh5 was played once. I can look at that game by searching the source database--Master Trends--for the resulting position, and I might have done so. But, the other two moves deserve and received more attention. With 3.Nc3, White scored 54% over twelve games, achieving a performance rating of 2411. 3.Nf3 is more common, but White's 49% scoring percentage over eighty games is less impressive, as is the 2336 performance. Nevertheless, it was my first candidate, so I opt to play it realizing I may be in for a tough game.

3.Nf3 d6

My opponent follows a well trodden path, and now my opening book shows me six moves that were played. Two account for the overwhelming majority.

4.Nc3

4.c3

The odd looking 4.c3 scores higher. I spent a few hours looking at some of those games and liked what I saw.

4.c3 Nf6 5.Qc2!?

5.d4 was played in a dozen games in my selective database, but I chose an obscure line played once in the past five years, and once in the 1970s. My opponent and I are now following Golovankov,V (2314)-Zacurdajev,D (2249), St Petersburg 2005, which was won by White.

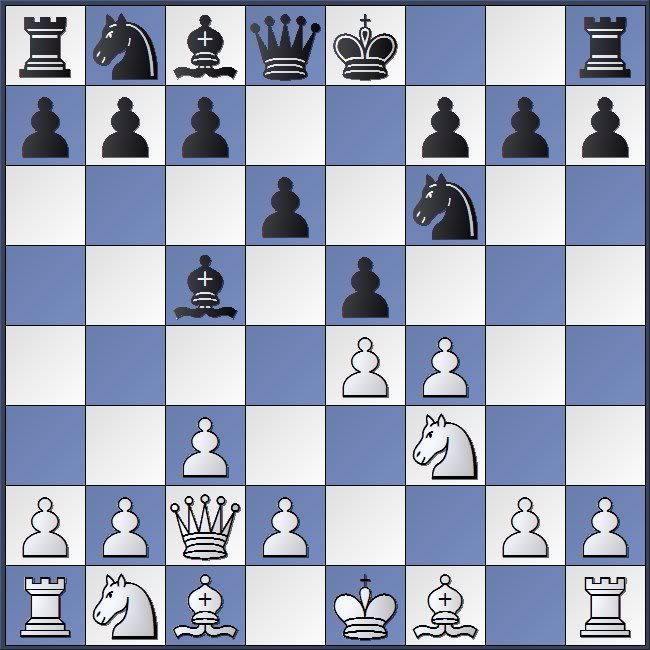

Black to move

5...Nc6 6.b4 Bb6 7.a4 a6

White to move

8.Bb2N

Even though White won, I was not fully satisfied with the line of play adopted. I wanted to push d2-d4, and that required preparation, so I introduced the novelty. My reference game continued 8.Be2 0–0 9.fxe5 dxe5 10.Na3 Ng4 11.h3 Nh6 12.d3 Be6 13.Ng5 Bd7 14.g4 f6 15.Nf3 Be6 16.Nc4 Ba7 17.Ne3 Nf7 18.Kf2 Kh8 19.Kg2 g6 20.h4 Qd7 21.g5 f5 22.b5 Ne7 23.c4 f4 24.Qb2 fxe3 25.Nxe5 Rg8 1–0

8...Ng4

Postgame analysis with an engine shows that 8...exf4 appears to be winning for Black. The novelty is not worthy of repeating should I ever find myself in this position again.

9.d4 0–0 10.Bc4?

Better was 10.b5 axb5 11.axb5 Rxa1 12.Bxa1 with a slight advantage for Black

10...exd4–+ 11.Nxd4 Ne3

11...d5!? is winning 12.Bxd5 Bxd4 13.cxd4 Nxb4–+

12.Qe2 Nxc4 13.Qxc4 Nxd4 14.cxd4 Qf6 15.0–0

The game is starting to shift back my way a little.

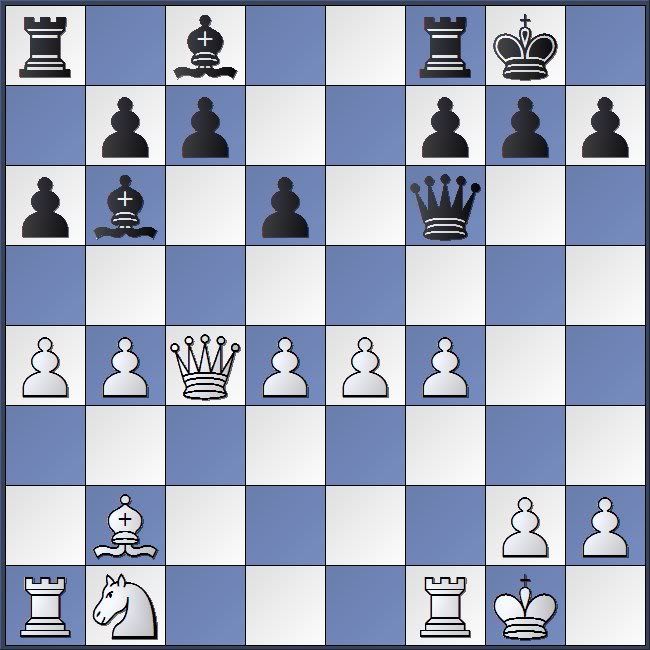

Black to move

15...c5

A better alternative: 15...d5 16.exd5 Re8 17.Nd2 with a slight advantage for Black

16.e5 dxe5 17.fxe5± Qg5 18.bxc5 Bc7

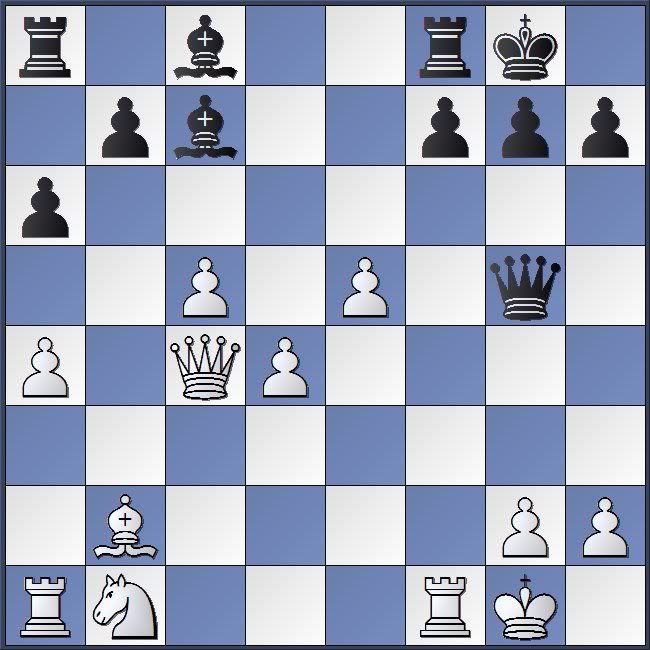

White to move

19.Nc3

Finally!

19.Na3 Bd7±

19.Ra3!

19...Bh3 20.Qe2+- Rad8 21.Ne4 Qg6 22.Ng3 Bg4± 23.Qe4 Qg5 24.Qf4 Qg6 25.Nf5+- Be2?? 26.Ne7+ 1–0

My opening choice and system led to failure, but it worked out okay in the end. I also won with Black, so this adversary and I now stand at four wins each.

A Bit of Deceit

I've described my process based on a selective database and opening book called Master Trends. I created those several years ago, and have tinkered with the process of creation a bit since. I'm currently using Master Trends III, although MT II was the latest when this game was in its early stages.

It may also be worth noting that my engine is able to use these opening books in the engine room at Playchess, where Hiarcs 10 running on my P-III Notebook has scored a few upset draws and wins against Rybka running on a 64-bit box. That experience tells me that the opening book is a quality product!

Wow! I had no idea it got so complex with databases & correspondence games. I have just started to flesh out the power of ChessAssistant with regards to opening prep recently so this is an eye opener.

ReplyDeleteI was thinking of taking up correspondence chess, but I really don't want to spend a bunch of time in front of databases.

Thanks for showing us a way to (create) play new openings in correspondence games (gameknot, RHP, ...).

ReplyDeleteI just installed Fritz 11 & Chessbase 9 on my computer and am pondering to buy Rybka 3 to include in my engines. Now i just have to find a manual that explains Chessbase 9 options starting from scratch. So although Steve Lopez at chesscafe does a good job it misses the bare essentials.

Thanks again and congrats with the showed game!

Wang,

ReplyDeleteSomehow it doesn't seem so complex to me, and databases cut out mountains of work that I did playing postal chess while using printed opening books. In those days, transpositions were a real nightmare, one I gradually learned to inflict more often than to suffer.

Some Chess Assistant users claim that program is even better than Chess Base for most purposes. I've only used the lite version that was available for free download (it may be still), and that was several years ago, so I cannot make a full comparison.

CT,

Google Steve Lopez T-Notes and you'll find columns he did a few years ago that cover some of the basics. Most of the CB 9 options will be the same as CB 6, 7, 8. Lopez covered each one, and wrote a series explaining how to do everything I mentioned here.