Although the best known early example of the sacrifice comes from Greco, he appears to have learned the idea from Alessandro Salvio (c.1575-c.1640), who published some lines employing the sacrifice in Trattato dell' Inventione et Arte Liberale del Gioco Degli Scacchi (1604).

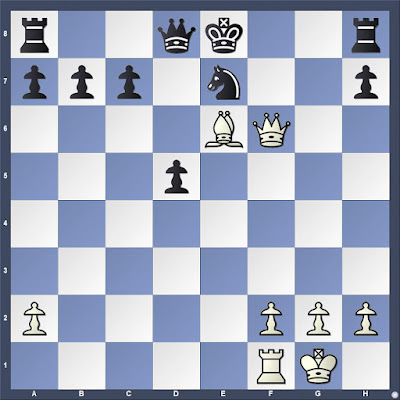

White to move

In 1996, Edward Winter posed the question in his column, "When was the Bxh7+/Ng5+ attack first played"?* He proceeds to demonstrate Irving Chernev's confusion on the matter, claiming Morphy -- Guibert, Paris, 1858 in Chess Review (April 1950) and in The Chess Companion (1968), while two pages later in this book Chernev suggests Paulsen -- Schwartz 1879. Winter asks, "what about Greco", noting that Chernev includes Greco's game in The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (1955), where it is game 199 (90).

The version of the game in Chernev's collection of miniatures is identical to the second variation of the twenty-third game in William Lewis, Gioachino Greco on the Game of Chess (1819) and game XXV, variation A in Professor Louis Hoffmann [Angelo Lewis], The Games of Greco (1900). Hoffmann's game and variations appear in David Levy and Kevin O'Connell, Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Vol. 1 1485-1866 (1981). This version, sans the variations in Lewis and Hoffmann, appears in ChessBase Mega 2020. Chessgames.com has Lewis's twenty-third game, instead of his variation A.

A longer version appears in Francis Beale, The Royall Art of Cheese-Play (1656). In Beale's version, Black's bishop first checks from b4 and then retreats to e7 after White's c-pawn blocks the check.

None of these books or databases offer the whole of Greco's analysis evident in his manuscripts. Both the extent of Greco's analysis and that which preceded his work becomes clear in "Part II. Openings and Games of the Classical Era of Modern Chess" (439-530) in Peter J. Monté, The Classical Era of Modern Chess (2014). I first mentioned this definitive work on Chess Skills with "Monumental Scholarship" (June 2020). Monté offers an analysis tree that ends every line with the names of sixteenth and seventeenth century manuscripts where these lines appear. He also references a few later published books, such as Beale, that are grounded in manuscripts.

Jon Edwards, Sacking the Citadel: The History, Theory and Practice of the Classic Bishop Sacrifice (2011) came into my possession a few days ago and provoked my interest in creating this article. Edwards attempts to give Greco his due, while acknowledging that Giulio Cesare Polerio may have "discovered it first" (8). He offers an admirable effort to present a more detailed biography of Greco and some context to place Greco in his times. Edwards draws on a number of Renaissance histories to construct his narrative. Unfortunately, he seems a little too trusting of dubious accounts and does not source his claims well. Some information is clearly grounded to a text, but mostly the author presents only a general bibliography of sources at the back of the book.

As Edwards tells it, Greco read Salvio's Trattato and Ruy Lopez's text, showed promise, and began studying with Don Mariano Marano (13-14). The claim that Greco studied under Marano derives from Richard Twiss, Chess (1787) and was repeated by Lewis in his book on Greco's games mentioned above (vii). Monté notes a number of historians who have expressed doubts concerning Twiss's claim. Salvio states only that Greco met Marano twice. Monté states, "an early acquaintance with Marano is based only on a rather vague suggestion by Salvio" (319).

That Greco was in Rome in 1619-1620 is better attested. No less than four extant Greco manuscripts exist from this time and indicate Greco's presence in Rome. Two of these manuscripts are undated and two are clearly dated early 1620. "[A]ll approximately dated facts of Greco's life are exclusively provided by his manuscripts", according to Monté (321).

Turning now to Monté's 90 page opening tree and documentation, we find variations containing the classic bishop sacrifice absent from the standard texts containing Greco's games (Beale, Lewis, and Hoffmann).

1.e4 e6 2.d4 c6

This strange move is absent from all modern references to Greco's games, but appears in three manuscripts of unknown authorship classified by Monté as part of the Lopez-complex: Elegantia, Regole, and Riccardiana (146, 156ff, 518). The idea is to bring Black's queen out with check. The check only occurs after White plays c4, a move recommended by Lucena.

3.Bd3 Be7 4.Nf3 Nf6 5.h4 Kg8&Re8

Castling, as we know it today, is older than Greco, but was not universally adopted. There were local variations. Some places there was a range of choices a player could make as to the squares where the king and rook ended up during the move. The placement of the rook on e8 makes the bishop sacrifice to come less forcing as Black's king has an additional option after accepting the sacrifice, as well as a second square for refusing.

6.e5 Nd5 7.Bxh7+ Kxh7 8.Ng5+

Black to move

The three main options 8...Bxg5, 8...Kg6, and 8...Kg8 all appear in Salvio's Trattato (1604). Greco adds additional lines or extends them. Because 8...Bxg5 has more variations, I begin with the other two.a) 8...Kg6 9.h5+

Salvio ends here. Greco adds:

9...Kh6 10.Nxf7+ K moves 11.Nxd8 with these moves appearing in the Orsini (1620) and Lorraine (1621) manuscripts.

b) 8...Kg8 9.Qh5 Bxg5 10.hxg5

This line is in Salvio, Orsini, and Lorraine.

c) 8...Bxg5 hxg5+

And now, Black has 9...Kg6, 9...Kg8 appearing in Salvio and two Greco manuscripts. I will not present all of this analysis. You can find it in Monté's book, and it reappears in the games of others in the twentieth century. Here Edwards' analysis shines.

Noteworthy is 9...Kg6 10.Qh5+ Kf5 11.Qh3+ Kg6 (11...Ke4 12.Qd3#) 12.Qh7# in Salvio, and two early Greco MSS. For 11.Qh3+, see below.

Lines with 3...Nc6 instead of 3...c6 do not appear in Salvio, but appear in a larger number of Greco manuscripts, beginning with Mountstephen (1623), one of the London MSS.

Game 1 in Edwards, Sacking the Citadel appears in ChessBase Mega 2020, Lewis, and Hoffmann.

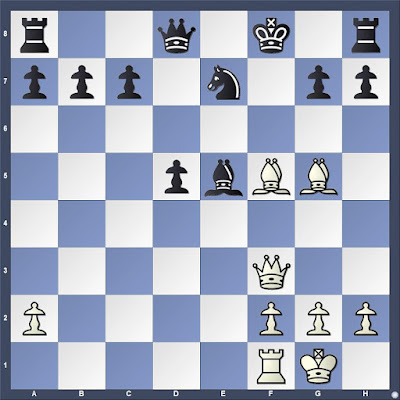

1.e4 e6 2.d4 Nf6 3.Bd3 Nc6 4.Nf3 Be7 5.h4 0-0 6.e5 Nd5 7.Bxh7+ Kxh7 8.Ng5+ Bxg5 9.hxg5+ Kg6 10.Qh5+ Kf5

White to move

11.Qh7+

Edwards comments, "Chernev was the first to mention a quicker checkmate with 11.Qh3+" (96). He does not indicate where Chernev offers this analysis. Nonetheless, the sequence appears in Salvio, as noted above, albeit with the difference that Black played 3...c6 instead of 3...Nc6.

11...g6 12.Qh3+ Ke4 13.Qd3# 1-0

It appears that Greco's early manuscripts are almost completely lifted from Salvio with respect to the French Defense and the classic bishop sacrifice. By 1623, however, Greco was developing his own ideas and adding variations.

Did Salvio, rather than Greco, first discover the Bxh7+ sacrifice? Perhaps not. In the Doazan manuscript, there may be an earlier version. The MS was sold in 1827 and then offered for sale again in 1841, In 1843, its new owner, Gabriel Eloy Doazan introduced it in an article in Le Palamède. When Doazan died in 1864, it was sold again and lost. The bulk of its contents were transcribed by Tassilo von der Lasa in 1855. It is from these transcriptions that we know much of its content.

Doazan dated the manuscript to 1600, but not much credence is given by historians to his claims.

The manuscript is of unknown authorship and date, but may reflect the work of Polerio and his associates. Some of the games are credited to other players. A line credited to Giovanni Domenico contains the classic bishop sacrifice.

1.e4 e6 2.d4 Nc6 3.Nf3 Be7 4.c3 Nf6 5.Bd3 O-O 6.h4 d5 7.e5 Ne8

Edwards comments, "Chernev was the first to mention a quicker checkmate with 11.Qh3+" (96). He does not indicate where Chernev offers this analysis. Nonetheless, the sequence appears in Salvio, as noted above, albeit with the difference that Black played 3...c6 instead of 3...Nc6.

11...g6 12.Qh3+ Ke4 13.Qd3# 1-0

It appears that Greco's early manuscripts are almost completely lifted from Salvio with respect to the French Defense and the classic bishop sacrifice. By 1623, however, Greco was developing his own ideas and adding variations.

Did Salvio, rather than Greco, first discover the Bxh7+ sacrifice? Perhaps not. In the Doazan manuscript, there may be an earlier version. The MS was sold in 1827 and then offered for sale again in 1841, In 1843, its new owner, Gabriel Eloy Doazan introduced it in an article in Le Palamède. When Doazan died in 1864, it was sold again and lost. The bulk of its contents were transcribed by Tassilo von der Lasa in 1855. It is from these transcriptions that we know much of its content.

Doazan dated the manuscript to 1600, but not much credence is given by historians to his claims.

The manuscript is of unknown authorship and date, but may reflect the work of Polerio and his associates. Some of the games are credited to other players. A line credited to Giovanni Domenico contains the classic bishop sacrifice.

1.e4 e6 2.d4 Nc6 3.Nf3 Be7 4.c3 Nf6 5.Bd3 O-O 6.h4 d5 7.e5 Ne8

White to move

8.Bxh7+ Kxh7 9.Ng5+ Bxg5 10.hxg5+

It appears that is as far as the game goes, but we know the possible conclusions.

Greco's games, especially if more of them were made available in databases, remain the most detailed early analysis of the classic bishop sacrifice. He copied lines from Salvio, and may have been exposed to ideas from even earlier. Greco developed these lines further.

It appears that is as far as the game goes, but we know the possible conclusions.

Greco's games, especially if more of them were made available in databases, remain the most detailed early analysis of the classic bishop sacrifice. He copied lines from Salvio, and may have been exposed to ideas from even earlier. Greco developed these lines further.

*Winter's question appeared in Kingpin (August 1996), and then again in Chess Notes 7979 "Greek Gift", which references the republication of the Kingpin column in Kings. Commoners, and Knaves (1999).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)