Over the past year (since September 2022), I have been working through this book deliberately and systematically, going through every game. Some games hold my interest a few minutes. Others sustain it an hour or more. Most days, I go through two or three games, often posting a position from one of the games on this blog’s Facebook page. I expect to go through the last ten games this week.

Last Tuesday, I posted a position from a blitz game that I won in seven moves. The winning idea was identical to that in Gibaud — Lazard, Paris 1924, the first game in Chernev’s classic. It was the second time I had employed this idea in online play.

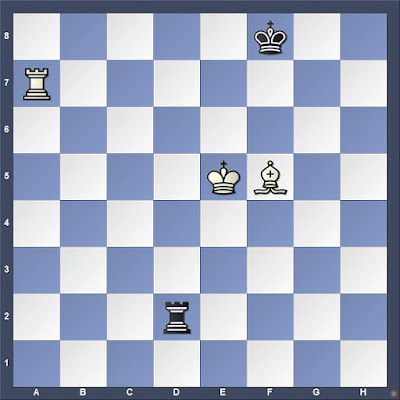

Black to move

Two weeks ago, Mattison — Nimzowitsch, Carlsbad 1929 (game 933 in Chernev) made such an impression on me that I pulled from my bookcase a book purchased last summer and started to read it. I bought Raymond Keene, Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal (1974) because it had been often recommended by IM John Donaldson, among others, and had not yet appeared on my shelf. In fact, I bought two copies: the original and Batsford’s algebraic edition (1999).

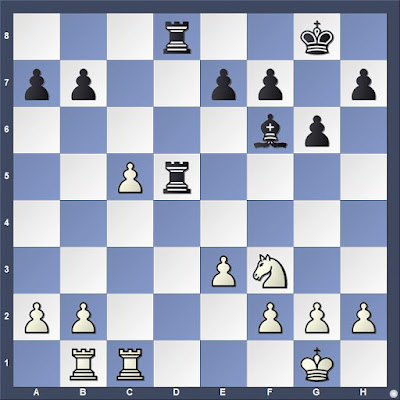

Saturday morning, I played one game online before heading to a youth chess tournament for which I served as the tournament director. While the children played, I showed my game to FM Jim Maki, who runs the analysis table at our youth events. Keene’s book guided some of the decisions I made during the game.

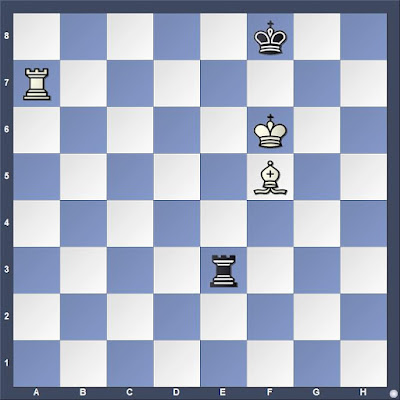

White to move

In the endless battle between bishops and knights, this position struck me as one that favored knights. Also, I was cognizant of Keene’s words.…superlative demonstration of good knight against bad bishop, … The bishops, locked behind the pawns, are never given a chance. (7)

And thirty pages later, these foci in Nimzowitsch’s play are made more explicit, Keene making the point that he had a clear preference for the knight over the bishop.

Ideally the rounded chess master should not harbour an idiosyncratic affection for one or other of the two minor pieces. However, Nimzowitsch did, and it is quite obvious from his games that he had a penchant for closed positions where he could exploit to the utmost the blockading potential of the knight.

Keene then presents a fantasy position that Nimzowitsch presents in Die Blockade, which “gives away his preference for the knight” (37).

Of course, there are other reasons learned from other books that might have led me to exchange bishop for knight. Many chess writers have emphasized the concept of time, for instance. I particularly recall studying this idea in Lasker’s Manual of Chess and Dan Heisman, Elements of Positional Evaluation. But, Keene’s work on Nimzowitsch was actively in my thoughts while playing.

Later in this same game, as I retreated a knight to maintain control of the central square it occupied, I recalled words of R. N. Cole, Dynamic Chess in reference to the play of William Steinitz. But these words were on my mind because Keene quotes them in discussion of the influences on Nimzowitsch.

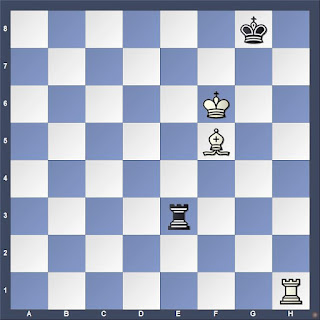

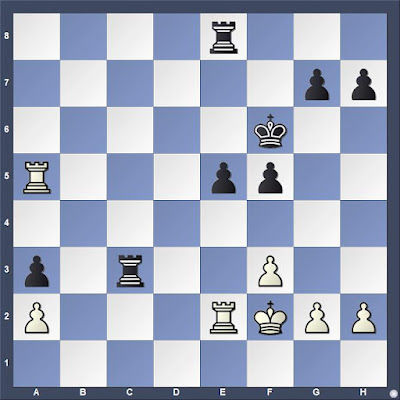

White to move

31.Nef3, which I played, is consistent with these ideas Keene credits to Steinitz and Nimzowitsch. Nonetheless, the engine on chessdotcom prefers that I would have transferred my rook to the b-file, and now sees an opportunity for Black to bring the nearly worthless light-squared bishop back into a position where it has some value.I was concerned that allowing Bxe5 would place a potentially vulnerable pawn on a strong point best utilized and controlled by my knights.