21 January 2023

The Strongest Move

20 January 2023

Some Books

The image on the right shows some of my current chess reading, but I tend to finish more when I have them as ebooks. Current active ebooks that I read in ChessBase include Nepomniachtchi: Move by Move (2021) by Cyrus Lakdawala, which I was reading more actively when it first came out than now. Another that I made substantial progress through before stalling (or taking a more active interest in other texts) is Alexander Raetsky, and Maxim Chetverik, Boris Spassky: Master of Initiative (2006). Vladimir Vukovic, The Art of Attack in Chess (1993) sat on my shelf many years and I read a couple of chapters, often referring back to these for review. When in early 2021 I acquired the new edition (2008) with corrections by John Nunn in ChessBase format, I read through the whole book in a little more than a month, using both ebook and print editions in tandem.

During a holiday sale last month, I added ebook versions of Garry Kasparov, My Great Predecessors (5 vols) and Kasparov on Kasparov (3 vols) to ChessBase. I have the print edition of My Great Predecessors and often read portions.

My shelf containing Chess Informants is nearly full. I have been a subscriber since 2015, getting each issue in print and CD format. I read the articles in the print edition and play through the games on screen. I also use the print edition for making notes (always in pencil). Informant first captured my interest in 1996 shortly after returning to active play at the Spokane Chess Club after more than 15 years away. I also took up postal chess again during that time. At the Washington Class Championships in Federal Way, my time between rounds put me in contact with David Weinstock, a bookseller. He had some Informants and showed me how the system of codes worked. Over the next several years I would sometimes buy an issue that was being sold at a discounted price because several newer editions were out. Then, early this century I bought a few electronic editions of multiple volumes that could be read in Informant’s propriety software. The company eventually stopped developing their own software and made their publication more compatible with ChessBase. Around this time, my ebook collection became complete (at least the games therein) and I maintain it as such through subscription (see “The New Informants”).

It is unlikely that I will ever finish László Polgár, Chess in 5333+1 Positions (1994), but recently have been going through portions of the 600 miniatures in the back of the book. These include some of the same games found in Irving Chernev, The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (1955), which was instrumental in transforming me into a chess player (see “My First Chess Book”). Since September, my progress through this book has been steady and consistent. The recent article, "Bramley -- Burgess 1946", developed from this project. This week, many of my students saw the game, Steinitz -- Pilhal 1860, which is number 518 in Chernev.

After reading Edward Lasker, The Adventure of Chess (1959) in December, I bought Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (1951), which I intend to read soon. I acquired it the day after Willy Hendricks, The Ink War: Romanticism versus Modernity in Chess (2022) arrived, a book that I dove into instantly. Hendriks' writing never fails to entertain as well as instruct.

In July, I am scheduled to give a presentation on chess pieces and history. Naturally, my knowledge must expand prior to then. The Art of Chess (2002) by Colleen Schafroth is a good book with excellent images, mostly from the collections at the Maryhill Museum of Art. A.E.J. Mackett-Beeson, Chessmen (1973) is a smaller book and less accurate in some historical matters. Two claims early in the book set me into verification and refutation mode at the outset. First, the author makes the common error of contending that an ancient Egyptian image of two people playing a board game—almost certainly senet—to be an early depiction of chess. And then, illogically, begins the narrative on the history of chess with a more plausible, but seemingly inaccurate description of chaturanga. Seeking a more accurate rendering drove me back into H.J.R. Murray, A History of Chess (1913), a book I read in-part, and often revisit.

Adriaan D. De Groot, Thought and Choice in Chess, 2nd. ed. (1978) is a classic text on memory, pattern recognition, and the relationships between playing chess well and what people try to define as intelligence. Last month, I finished reading Scott Barry Kaufman, Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined (2013), which I had started in October. The book came to my attention while writing an article about chess talent in which I argued that capacity for hard work was more vital than any sort of so-called natural ability. A magazine article by Kaufman on the nature of talent brought his work to my attention.

11 January 2023

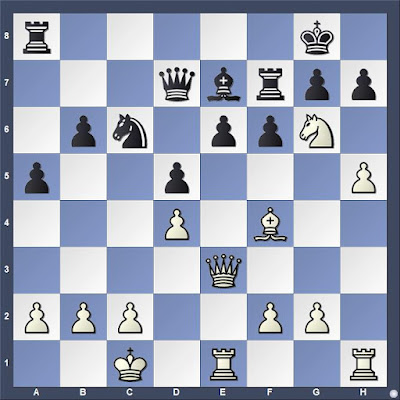

Mate in Six

Position arose in Schulten — Kieseritzky, Paris 1844, which is game 511 in Irving Chernev, The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (1955).

In September 2022, I started working my way through all the games in this book. This game was the first one this morning. I may go through as many as five before heading to work.

07 January 2023

Bramley -- Burgess 1946

That afternoon, I showed the game to my after school chess club. On Wednesday, I spent more time exploring the game, annotated it, and created a worksheet for my students with positions derived from the game--mostly those that did not occur. Captions under diagrams indicate the positions on the worksheet.

I cannot find any information about the game beyond what Chernev offers--only surnames, location, and year. Another book includes the game, László Polgár, Chess: 5334 Problems, Combinations, and Games, but derived from Chernev. The game is number 500 in Chernev. Polgár includes it among 100 miniatures with sacrifices on f2/f7.

Surrey, 1946

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Nf6 5.d4

5.d3 is the top choice of masters

5...exd4 6.cxd4

6.b4 Be7;

6...Bb4+ 7.Nc3

This move initiates the Greco Attack, which I have explored in several articles on Chess Skills.

7.Bd2 also preferred.

7...Nxe4 8.0-0

8.d5

8...Nxc3

8...Bxc3 9.d5 Bf6 10.Re1 Ne7 11.Rxe4 d6 Although approximately equal, Black tends to do better.

9.bxc3 Be7?!

Here we reach what struck me as a novelty when I first looked at the game. It has been been played by others, even at least once by a chess master.

9...d5 10.Re1+ Be7 11.Bd3

10.Re1

Better is the immediate 10.d5 Nb8 (10...Na5 11.Bd3) 11.d6! (11.Re1 reaches the game) 11...cxd6 12.Bxf7+ Kxf7 13.Qd5+ Kf8

|

| Analysis diagram |

14.Re1 Na6 15.Ng5 Qe8 16.Bf4 Nc7 17.Qf5+ Kg8 18.Bxd6 Ne6 19.Nxe6 dxe6 20.Rxe6 Bxe6 21.Qxe6+ Qf7 22.Qxe7 Qxe7 23.Bxe7 Kf7 24.Bc5 Rhd8 and drawn in 63 moves. Chen,Y (2081) -- Kislik,E (2347) Budapest 2011.

14.Ng5 Bxg5 15.Bxg5 Qe8 16.Rfe1 Qf7 17.Qxd6+ Kg8 18.Re7 Nc6 and White won in 32 moves. Sizov,A -- Prikhodko,P Serpukhov 2001.

10...0-0

10...d5 11.Bd3 0-0 12.h3 Be6 13.Bf4 Qd7 14.Rb1 b6 15.Qd2 Bd6 16.Bxd6 Qxd6 17.Re2 h6 18.Rbe1 Rfe8 19.Bb5 f6 20.a4 Bf7 ½-½ Boricsev,O (2343) -- Sevostianov,P (2248) Mukachevo UKR 2017.

11.d5 Nb8

Both players have made errors, but White seems to be much better.

11...Na5 would be my inclination 12.d6! (12.Bd3) 12...cxd6 13.Bd5 Nc6 14.Ba3 Bf6 15.Qd3 (15.Rb1) 15...Ne7 16.Be4 g6 17.Bxd6+-

12.d6!

Lichess opening explorer shows that eleven other moves have been employed here, but none with the sort of results garnered by 12.d6! 12.Qe2 has been the most popular and Stockfish likes it almost as well.

12...Bf6

12...cxd6 13.Ba3 Nc6 14.Bd5 White's advantage is clear;

12...Bxd6?

|

| Analysis: Exercise 2 |

White could have struck now with 13.Bxf7+! Rxf7 14.dxc7 Qf8 (14...Qxc7 15.Re8+ Rf8 16.Qd5+ Kh8 17.Rxf8#) 15.cxb8Q Rxb8 16.Ba3 Be7 (16...Qxa3?

|

| Analysis: Exercise 6 |

17.Rxe7 Rxe7 18.Qd5+ Qf7 19.Qd6+-

13...Qxc7 14.Ba3

Again, White could have played 14.Bxf7+! Kh8 15.Bb3

14...Bxc3

Why not trade a rook for two bishops? 14...Qxc4 15.Bxf8 Kxf8?

|

| Analysis: Exercise 1 |

15.Bxf7+!

During chess club, I was asked what if Black captures the bishop.

15...Kxf7

|

| Analysis: Exercise 5 |

Matters end more quickly if the rook nabs the bishop. 15...Rxf7 16.Re8+ Re7 17.Rxf8#

16.Bxf8 Bxe1

|

| Exercise 3 |

Black can delay, but not prevent checkmate. 1-0

01 January 2023

Puzzles

My puzzle rating on 19 December was 2806 with a peak rating of 2849. My puzzle rating at the end of the year was 2855 with a peak of 3002. I crossed over 3002 early Christmas morning, but became greedy in an effort to surpass a friend who was at 3012. An hour later I had fallen to 2702 (see “Blitz Addiction”). I got back to 2802 before I quit. through the last week of the year, I labored to keep my puzzle rating over 2800.

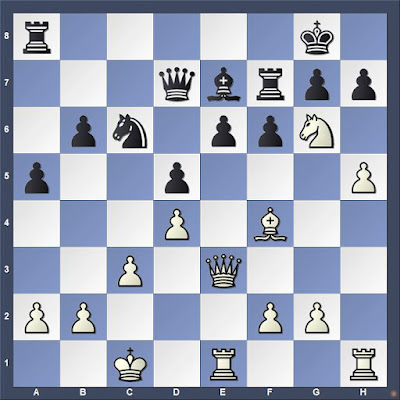

These are the last three that I failed in my final session on New Year's Eve.

Puzzles on chess.com can be instructive. They can be rewarding. In the last two weeks of 2022, I found them addicting.

Often I find more benefit in puzzles from books. The sequencing of puzzles in The Manual of Chess Combinations by Sergey Ivashchenko provide instructive value that is missing from all online tactics training. I could benefit from working through volume 2, which is at the right level for my current skill. Like the exercises that chess.com feeds me, I should get most of them correct when I am focused. Volume 1 is easier, but I made a personal commitment to do all the more than 1300 exercises in one year's time. I started at the end of February and have about 500 more to go.

The difficulty of the puzzles in Paata Gaprindashvili, Imagination in Chess: How to Think Creatively and Avoid Foolish Mistakes (see my review, “Imagination in Chess”) keep calling me. They offer no instant rewards with a meaningless online rating, but instead offer deeper satisfaction when I solve them correctly. These puzzles are on par with volume 3 of The Manual of Chess Combinations by Alexander Mazja.