Other books, too, might be on the docket as I decide how much time should be given to this one position.

As I wrote in “Ten Books to Achieve 1800+”, I started playing the Sicilian Defense in the 1970s. In the late 1990s, I became enamored with the Kalashnikov variation and sought to memorize the critical lines, inevitably finding myself in trouble when White played a move outside my book knowledge. In 2003, I took up the French, which is not a better defense for Black. In fact, it might be worse. But, my approach to understanding the opening was altered.

Memorization of lines grows out of comprehension of the ideas, rather than the reverse. Now, Engqvist pushes me to comprehend the ideas in some move order nuances of Sicilian lines that I often reach via the French when White opts to play something other than 2.d4.

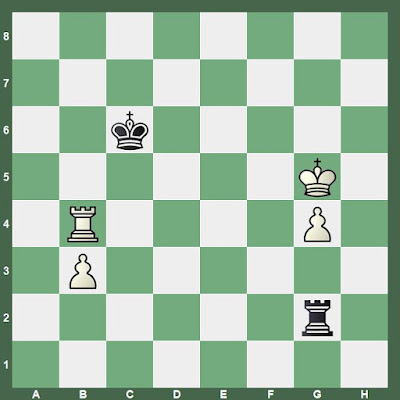

After writing and posting the above, I continued with the next positions in Engqvist's book. Three of today's five positions are from a single game (a feature I like about Lev Alburt and Al Lawrence, Chess Training Pocket Book II (2008)--one of the 300 positions series). Engqvist's analysis references some by the winner of the game, and his book of selected games has been ordered.

As I wrote in “Ten Books to Achieve 1800+”, I started playing the Sicilian Defense in the 1970s. In the late 1990s, I became enamored with the Kalashnikov variation and sought to memorize the critical lines, inevitably finding myself in trouble when White played a move outside my book knowledge. In 2003, I took up the French, which is not a better defense for Black. In fact, it might be worse. But, my approach to understanding the opening was altered.

Memorization of lines grows out of comprehension of the ideas, rather than the reverse. Now, Engqvist pushes me to comprehend the ideas in some move order nuances of Sicilian lines that I often reach via the French when White opts to play something other than 2.d4.

After writing and posting the above, I continued with the next positions in Engqvist's book. Three of today's five positions are from a single game (a feature I like about Lev Alburt and Al Lawrence, Chess Training Pocket Book II (2008)--one of the 300 positions series). Engqvist's analysis references some by the winner of the game, and his book of selected games has been ordered.