Booth -- Fazekas [C18]

London, 1940

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 Qc7 7.Nf3 Nc6

Third most popular move.

7...Ne7 is most common.

8.Bd3

Black to move

8...cxd4

This capture does not get played by masters, but there are 23 games between lesser players in ChessBase Mega 2020. Also, there are 123 games in Lichess database, including several players of Black rated over 2300.

8...c4 9.Be2 seems appropos.

9.cxd4 Nxd4??

Loses the knight. ChessBase Mega has 18 games with this error; Lichess has 67.

10.Nxd4 Qc3+

White to move

Black has forked knight and rook and White can only defend one of them.

11.Qd2

Naturally, there are a number of games where White played Bd2, opting to give up the knight.

11...Qxa1? 12.c3!

The rook was poison. Five games in ChessBase Mega 2020 go this far. The highest rated Black player is 2153. Four games on Lichess--all players over 2000 on that site. Black appears to have resigned here as the queen is trapped. A game on Lichess continued 12...Qxc1+ 13.Qxc1 and then Black gave up.

1-0

In my game, my opponent did not blunder the knight. I still trapped the queen, but with less advantage. Alas, I moved the knight to the wrong square and let the queen back out.

Stripes -- Internet Opponent [C17]

Live Chess Chess.com, 22.09.2022

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Nf3

5.a3 was Booth -- Fazekas.

5...a6

A rare move: 145 games on Lichess; 16 in ChessBase Mega 2020

6.a3 cxd4

6...Bxc3+ 7.bxc3

7.Nxd4 Bxc3+ 8.bxc3 Qc7

22 games between Lichess (20) and ChessBase (2) have reached this position.

9.Bd3

This move was a novelty in the position, but played in recognition of the trap.

9...Qxc3+

11.Qd2

Naturally, there are a number of games where White played Bd2, opting to give up the knight.

11...Qxa1? 12.c3!

The rook was poison. Five games in ChessBase Mega 2020 go this far. The highest rated Black player is 2153. Four games on Lichess--all players over 2000 on that site. Black appears to have resigned here as the queen is trapped. A game on Lichess continued 12...Qxc1+ 13.Qxc1 and then Black gave up.

1-0

In my game, my opponent did not blunder the knight. I still trapped the queen, but with less advantage. Alas, I moved the knight to the wrong square and let the queen back out.

Stripes -- Internet Opponent [C17]

Live Chess Chess.com, 22.09.2022

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Nf3

5.a3 was Booth -- Fazekas.

5...a6

A rare move: 145 games on Lichess; 16 in ChessBase Mega 2020

6.a3 cxd4

6...Bxc3+ 7.bxc3

7.Nxd4 Bxc3+ 8.bxc3 Qc7

22 games between Lichess (20) and ChessBase (2) have reached this position.

9.Bd3

This move was a novelty in the position, but played in recognition of the trap.

9...Qxc3+

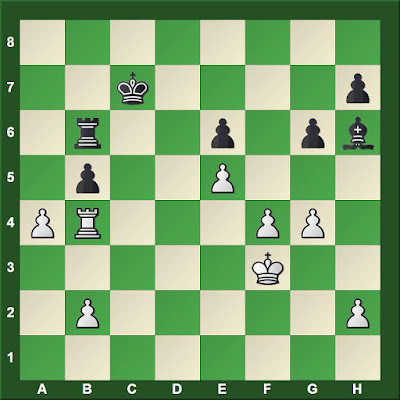

White to move

The position differs in particular ways from the London miniature. Compare the two diagrams.

10.Qd2!=

Booth's Qd2 gave a clear advantage

10...Qxa1??

10...Qxd2+ 11.Bxd2=

11.c3!

The queen is trapped.

11...Nc6 12.Nc2??

Lets the queen escape.

12.Nb3+-

10.Qd2!=

Booth's Qd2 gave a clear advantage

10...Qxa1??

10...Qxd2+ 11.Bxd2=

11.c3!

The queen is trapped.

11...Nc6 12.Nc2??

Lets the queen escape.

12.Nb3+-

Black to move

12...Qa2-+

I could have resigned here, but it was a rapid game and I was able to make some threats. My opponent needed several moves to get the queen back with its compatriots. In the end, facing a desperate check, my opponent moved the king to the wrong square handing me a mate in three. I did not fail a second time in this game.

I could have resigned here, but it was a rapid game and I was able to make some threats. My opponent needed several moves to get the queen back with its compatriots. In the end, facing a desperate check, my opponent moved the king to the wrong square handing me a mate in three. I did not fail a second time in this game.