Youth chess has had a profound impact on my thinking about the game. In countless youth events, I have watched children playing out rook and king vs. lone king. Often one of them tells the other, "I think this is a draw." Sometimes they look at me for confirmation. When the stronger side has a queen, they know it should be a win, but often cannot find it. Check, check, check, ... but never checkmate.

Having observed such scenes several times in my first few youth events as a coach more than twenty years ago, I made it a point to teach elementary checkmates to my students. I have spent hundreds of hours teaching checkmate with queen and rook, or coordinating one of them with the king against a lone king. The first eleven endgames in Bruce Pandolfini,

Pandolfini's Endgame Course (1988) became a valuable resource for teaching.

|

| Some books on checkmate |

I have added to Pandolfini's basic positions a great many others, some composed, some from games where a player executed a checkmate well, or where someone failed. Other books have expanded my resources. William Lewis,

Elements of Chess (1819) is a neglected gem. It contains very few diagrams, so it is not always easy to appreciate at a glance the sorts of positions he offers for training new players. Last month's post "

Elementary" shows one that I find useful.

Several posts here on

Chess Skills have outlined how I teach elementary checkmates with few pieces to children. Both Pandolfini and Lewis are mentioned in "

Teaching Elementary Checkmates" (2014). Both "

Cutting Off" (2015) and "

Playing with Rooks" (2016) offer additional examples as they document lessons as I use them in after school clubs.

Older Beginners

Not all beginners are children, of course. Chess is enjoying growth in popularity at the present. Some adults are returning to the game after many years away. Others are taking it up for the first time. Chess groups on Facebook and forums on several chess sites are inundated with requests for advice for those starting out.

My standard refrain is to point these seekers to "

Advice for Beginners", which I wrote last January. At the core of that advice is Jose Capablanca,

Chess Fundamentals (1921). I have adopted Capablanca's sequence from this book in my own teaching. He starts with simple checkmates, and appears to suggest a pattern that starts at the end of the game and works towards the beginning.

Chess Fundamentals and the companion volume

A Primer of Chess (1935) offer instruction in basic checkmates with few pieces, as well as some middlegame combinations where checkmate is possible, or where a checkmate threat forces concessions. Something more is needed to address some of the failures I have observed in games after game of beginning players, young and old.

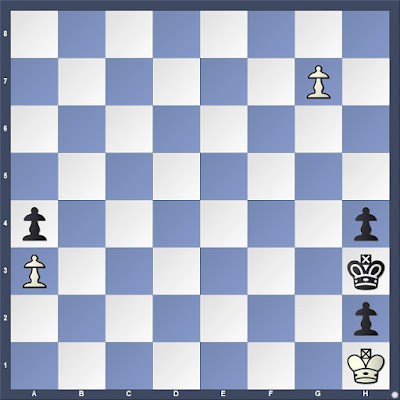

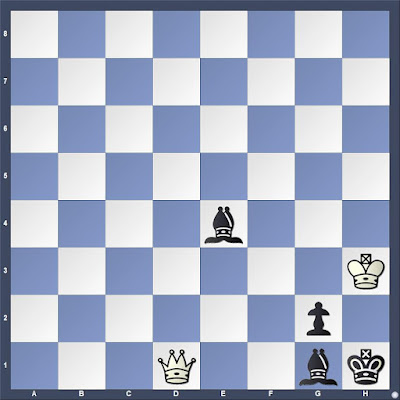

The position below arose in a game between two beginners. One has been playing chess less than three months, but the other has been playing at least seven years. Naturally, there are a great many errors in the game that could be highlighted.

Black to move

When I reached this position while playing through the game, I instantly saw an unforced checkmate in two. Consequently, calculation begins with 26...Qh3+ 27.Kg1 (Ke2 walks into checkmate). It does not take long to see a sequence involving bishop and queen that can be found in dozens of exercises in books and online.

For instance, Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn,

The Art of the Checkmate offer Mate No. 12C.

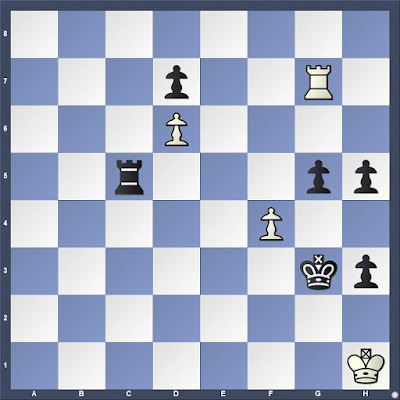

White to move

They opine, "Nine times out of ten, the beginner will play QxP ch, and be surprised afterward to find that the king is able to escape after all" (140). In the 2015 Batsford translation, these words are rendered, "The novice has a tendency to play 1. Qxh7+ and it is quite a surprise to see that the attacked king manages to take flight."

The mating sequence is

1.Bxh7+ Kh8 2.Bg6+ Kg8 3.Qxh7 Kf8 4.Qxf7#.

In the game, the experienced beginner played 26...Qh1+ and lost ten moves later when the newer beginner found a mate in one.

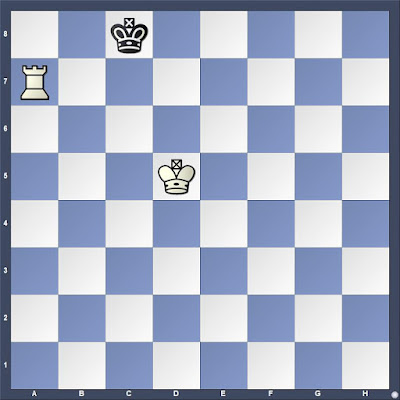

White to move

Diagnosing Failure

In the game above, Black had 46 seconds remaining (of an initial five minutes) when this position was reached.

Black to move

was played. Three seconds were spent on this move. Does the player feel rushed when under one minute? Is the player oblivious to the presence of the bishop? If so, he may have feared that the queen could be captured. The queen was left

en prise later in the game. In fact, Black had six seconds remaining when

34...Qxf2 was played instead of 34...Qxa7. That error led to the checkmate. Both queens were

en prise on move 34.

The player of the Black pieces has played more than 1400 blitz and rapid games on chess.com. In the past 500 games, 140 have ended with checkmate by the queen. In many cases, the queen has been supported by a bishop, but more often by a knight or rook.

This one is typical.

My impression from looking through all 140 queen checkmates in these 500 games leads me to the belief that the player in question knows a few checkmate patterns, but could benefit from learning more.

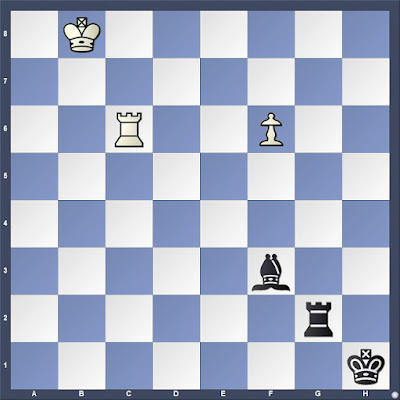

Another game illustrates our experienced beginner in pursuit of a checkmate with bishop and queen that he has executed in several prior games.

Black to move

24...Bb324...Qxd3 was far better. In fact, it is the only move that maintains the advantage. It threatens Qb1# and Ne2#. I suspect that Black had ambitions of playing Qxd3 next with the idea to play Qc2#. That pattern appears several times in the player's games.

25.Rde1 Qxd3 26.Nd4Now White has c2 defended.

26...Nf5Black hopes to remove the knight.

27.Bxb727.Be4 wins simply, but White gets credit for opening the g-file in a way that allows Black to continue with a plan that is too slow.

27...Nxd4 28.Qxg7#Black's pursuit of a plan was performed without recognition of White's threats.

The Remedy

Resources are abundant for a beginner or even intermediate player who wishes to improve their understanding of checkmate patterns. The popular playing site, Lichess offers a series of lessons where certain named patterns can be played against a chess engine. Navigate to Learn > Practice from the menu.

Books offer greater depth.

When David Weinstock, whom I had just met, recommended to me Renaud and Kahn,

The Art of the Checkmate, I recall thinking to myself that he was underestimating my chess skill. I believed that checkmate was a skill I had developed well. I was a C Class player in the USCF rating system who had recently returned to active chess after more than a decade of only occasional casual games. Two decades earlier in high school, I invested many hours practicing checkmates with heavy pieces and even the bishop pair. While playing through master games, I often continued them beyond the resignation to work out the checkmate possibilities.

Despite my attitude that I was beyond the need for such study, I examined the book carefully when I saw it in Auntie's, Spokane's independent bookstore. It did not take long to realize that it offered a little more depth than I had imagined when David mentioned it. I bought the book and started working through it. New checkmate patterns began to appear in my games.

The Art of the Checkmate has become one of the books that I recommend more often than most others. Few other books offer the quality of instruction on a matter of such foundational importance to developing chess skills. The authors offer 23 basic patterns. Most have several variations. They illustrate each one with the essential pattern of the pieces and the moves making up the mating sequence. These patterns are followed by illustrations from composed studies, game fragments, and whole games. Quiz sets follow each of the five sections.

Other Books

A few years ago, another group of books for teaching and learning checkmate patterns were brought to my attention. Someone suggested that I take a look at Mikhail Tal and Victor Khenkin,

Tal's Winning Chess Combinations (1979). This book, which I found used at a reasonable price, takes each piece separately, examining how it is typically used to effect checkmate. Each piece, excluding the king, is given a chapter. Eight additional chapters treat two pieces in concert, such as queen and bishop or queen and knight. The last chapter considers several combinations of three pieces.

This position illustrates a back rank checkmate threat that leads to winning material.

Black to move

1.Qb2Victor Henkin,

1000 Checkmate Combinations (2011) is a newer translation of the same Russian text, according to Vladimir Barsky, it is titled

The Last Check. Both books are out of print, hard to find, and consequently expensive, except that the newer text has been available in Kindle format. It is scheduled to be released again in paperback in February 2022. Barsky,

A Modern Guide to Checkmating Patterns (2020) adopts Khenkin's methodology, drawing only from games played in the twenty-first century. I discussed these three books in greater detail in "

Checkmating Patterns" (2020).

I am less enthusiastic about Murray Chandler,

How to Beat Your Dad at Chess (1998). This book offers excellent illustrations of basic patterns with abundant diagrams, and adds a few tactical motifs for breaking through the opponent's defenses. It is probably an excellent choice for children, while being suitable for adults as well. My lack of enthusiasm for the book stems from its lack of depth. It offers fewer examples and far less instructive discussion than

The Art of the Checkmate and also found in Khenkin's text. Several of the "50 Deadly Checkmates" promised by the book are tactics that win material that seem to have been included to reach that magic number 50.

Victor Vukovic,

The Art of Attack in Chess has a chapter presenting checkmate patterns.

Improve Your Chess Now by Jonathan Tisdall lists common checkmate patterns in an appendix. I used these two, as well as Chandler, and Renaud and Kahn while creating a list of 37 patterns that I organized into groups: corridors, diagonals, intersections, knights, queens, and combinations. I created seven sets of worksheets with instructive material for my students and printed a few copies of the whole manuscript, also offering for sale a PDF version under the title "A Checklist of Checkmates". My list appears at "

Checkmate Patterns" (2017). This work contains errors that I would like to correct (see "

Pillsbury's Mate").

Antonio Gude,

Fundamental Checkmates (2016) deserves more attention. I have had this book for a few years, but it sits on my shelf untouched while I keep returning to those I know better. The instructive portion combines the approach of Renaud and Kahn with that of Victor Khenkin and then extends both with nearly 100 pages devoted to sacrifices, organized by the piece giving itself up. Three sets of exercises total 317 problems with solutions.

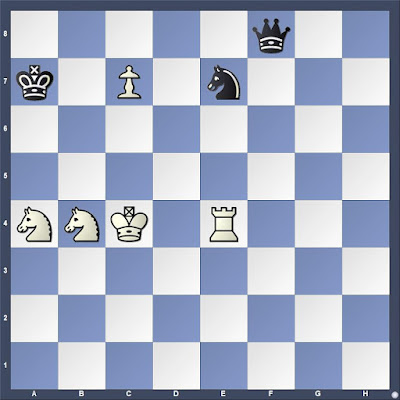

The well-known combination sacrificing a queen to deliver smother mate with a knight is often called Philidor's Legacy, although many others credit Gioachino Greco because of this combination.

Black to move

15...Nf2+ 16.Ke1 Nd3+ 17.Kd1 Qe1+ 18.Nxe1 Nf2#.

Gude credits the historian Joaquin Perez de Arriga with pointing out that the combination appears in Luis Ramírez de Lucena,

Repeticion de Amores e Arte de Axedrez (1496).

White to move

Gude even points out that Lucena, "specifies that the solution must not include the capture of any black piece" (19). Fundamental Checkmates is far more comprehensive than the books I usually recommend. Moreover, as a historian I must acknowledge that Renaud and Kahn perpetuate errors, while Gude seeks to dispel misunderstanding.

Having opined in the Chess Book Collectors" group on Facebook that The Art of the Checkmate and 1000 Checkmate Combinations were far superior to other book on the subject, I was exposed to alternative views. Gude was mentioned right away. Later in the thread, someone mentioned a text that I did not know about, but that now occupies space on my bookshelf. George Koltanowski and Milton Finkelstein, Checkmate!: The Patterns of the Winning Mating Attacks and How to Achieve Them (1978) will not find a place among those I recommend to beginners who will not take the time to learn English descriptive notation, nor benefit particularly from tracking down a now rare book that could be quite expensive. However, as I make time to read through it, it likely will present me with some new lessons for my students.

For most chess players willing to put in a little work, Renaud and Kahn remains a excellent choice. Soon, Henkin, 1000 Checkmate Combinations will be available, too. For those looking to work less, or seeking something easier for children, How to Beat Your Dad at Chess is worthy of attention. For those of who teach checkmate, Gude, Fundamental Checkmates is a valuable resource.