The chess games of Alexander McDonnell (1798-1835) offer abundant instruction in tactics. McDonnell, born in Belfast, Ireland, is considered to have been the strongest chess player in Great Britain during the early 1830s. He is most often remembered, however, for his matches with Louis-Charles Mahé de La Bourdonnais (1795-1840). McDonnell lost more than half of their 85 games played during six matches. He was thus the runner-up in the first unofficial world chess championship. He also won 27 of those games, however.

For the past several days, I have working through McDonnell's games during my morning coffee. My intention is to go through all of his available games (ChessBase has 110; chessgames.com has 105). Most of his play was at odds, as was customary in his day, so the selection of available games in databases is small. There are 35 games in addition to the match games against Bourdonnais. Two of these are short losses to Captain William Davies Evans, including what is probably the oldest recorded instance of the Evans Gambit. Most of the rest are games played during simuls.

After going through these 35 games neither as fast as Jeremy Silman claims was his habit as a young player, nor slow enough to understand every nuance, I reached the La Bourdonnais match games this morning. They appeared to play by a rule that would remain common for the next several decades: draws do not count and must be replayed. Hence, La Bourdonnais had White through the first four games. Each draw led to another game with the same colors.

Although all drawn, the first three games were battles from the first moves to the finish.

De Labourdonnais,Louis Charles Mahe -- McDonnell,Alexander [C21]

London m1 London (1), 1834

1.e4 e5 2.d4 exd4 3.Nf3 c5 4.Bc4 Nc6 5.c3 Qf6 6.0–0 d6 7.cxd4 cxd4 8.Ng5 Nh6 9.f4 Be7 10.e5 Qg6 11.exd6 Qxd6 12.Na3 0–0 13.Bd3 Bf5 14.Nc4 Qg6 15.Nf3 Bxd3 16.Nce5 Bc2 17.Nxg6 Bxd1

White to move

18.Nxe7+

18.Nxf8? loses material. 18...Bxf3. After the text, White remains down only the sacrificed pawn and retains a slight initiative.

18...Nxe7 19.Rxd1 Nhf5 20.g4 Ne3 21.Bxe3 dxe3 22.Rd7 Rfe8 23.Re1 Ng6 24.f5 Nf4 25.Rd4 Nh3+ 26.Kg2 Nf2 27.Rc4 Rad8 28.h3 h6 29.Re2 b5 30.Rd4 Rxd4 31.Nxd4 a6

La Bourdonnais's aggressive play has led to exchanges and an ending where Black retains the advantage of one pawn, albeit one that will fall.

White to move

32.Kf3 Nxh3 33.Rxe3 Ng5+ 34.Kf4 Rxe3 35.Kxe3

And now it is a knight ending with pawns on both sides. Such knight endings are often sought by players substantially stronger than their opponents because they offer better prospects of victory than rook endings.

35...g6 36.fxg6 fxg6 37.Nc6 Ne6 38.Ke4 Kf7 39.Ke5 h5 40.gxh5 gxh5

White to move

McDonnell has the advantage, but La Bourdonnais has the draw well in hand. As long as he holds, he gets another game with the White pieces.

41.Kf5 Nc7 42.b3 Ke8 43.a4 bxa4 44.bxa4 Nd5 45.Kg5 Ne7 46.Nb8 a5 47.Na6 Ng6 48.Kxh5 Nf4+ 49.Kg5 Ne6+ 50.Kf5 Kd7 51.Ke5 Nd8 ½–½

De Labourdonnais,Louis Charles Mahe -- McDonnell,Alexander [C44]

London m1 London (2), 1834

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 exd4

Switching the move order of the first game has led to the Scotch Gambit, an opening occasionally employed as a surprise weapon in our day.

4.Bc4 Qf6 5.c3 d3 6.Qxd3

This time, White recovers the pawn quickly.

6...d6 7.0–0 Qg6 8.Bf4 Be7 9.Nbd2 h5 10.Rfe1 Bh3

McDonnell, too, shows some aggression.

White to move

11.Nh4 Bxh4 12.Qxh3 Bf6 13.e5 dxe5 14.Bxe5 Bxe5 15.f4 Nge7 16.fxe5

This time, it is White who has a vulnerable e-pawn that is far advanced.

16...Qg4 17.Qxg4 hxg4 18.Nb3 Ng6 19.e6 f5 20.Rad1 Nge5 21.Bd3 Rh5 22.Bc2

Black to move

22...Ke7 23.Nd4 Kf6 24.Rf1 Ne7 25.b4 Rah8 26.Ne2 Rxh2

McDonnell wins a pawn.

27.Ng3 g6 28.Bb3 Kg5 29.Rde1 Nd3 30.Re3 Nf4 31.Rf2 R2h7 32.Rd2 Nh5 33.Nxh5 Rxh5 34.Kf2 f4 35.Re5+ Nf5 36.e7 Re8 37.Rd7

Black to move

La Bourdonnais is positioned to win back a pawn, but McDonnell finds the way to another ending with a one pawn advantage.

37...Rh7 38.Rxc7 Rhxe7 39.Rcxe7 Rxe7 40.Rxe7 Nxe7

White to move

The players reach a minor piece ending where the bishop must contend with a knight that fights alongside a superior number of pawns.

41.a4 Kf5 42.a5 Ke5 43.Bd1 g3+ 44.Kf3 Nd5 45.Bc2 g5 46.b5 Nxc3 47.b6 axb6 48.axb6 Nb5 49.Kg4 Nd6 50.Bd3 Ne4 51.Be2 Kd5 52.Bf3 Ke5 53.Be2 Kf6 54.Bf3 Nf2+ 55.Kh5 g4 56.Bxg4 Ke7 57.Bc8 Kd6 58.Bxb7 Kc5 ½–½

The Frenchman survives again.

De Labourdonnais,Louis Charles Mahe -- McDonnell,Alexander [C44]

London m1 London (3), 1834

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 exd4 4.Bc4 Qf6 5.0–0 d6 6.c3 d3 7.Qxd3 Qg6 8.Bf4 Be7 9.Nbd2 Nh6

McDonnell deviates from the previous game.

White to move

10.Rae1 0–0 11.Nd4 Ne5 12.Bxe5 dxe5 13.N4f3 Bd6 14.h3 Kh8

Preparing to thrust the f-pawn forward.

15.Nh4 Qh5 16.Qg3 f5 17.Nxf5 Nxf5 18.exf5 Bxf5 19.Ne4 Bxe4 20.Rxe4 Rf6 21.Rh4 Qf5 22.Qe3 Qd7

White to move

The tension builds in the match as the players keep their queens on the board longer than the first two games.

23.Bd3 g6 24.Be4

La Bourdonnais sets the stage for Aron Nimzovich to articulate the concept of blockade.

24...Raf8 25.Qg3

The g-pawn is threatened.

25...Qg7 26.b4 a5 27.a3 axb4 28.axb4 c5 29.Rb1 cxb4 30.cxb4 Bc7 31.Kh1

Black to move

31...Rb6

31...Rxf2? 32.Bxg6

32.b5 Bd8 33.Rg4 g5 34.Bf3 h5 35.Re4 g4 36.hxg4 hxg4 37.Qxg4 Rh6+ 38.Kg1 Qh7

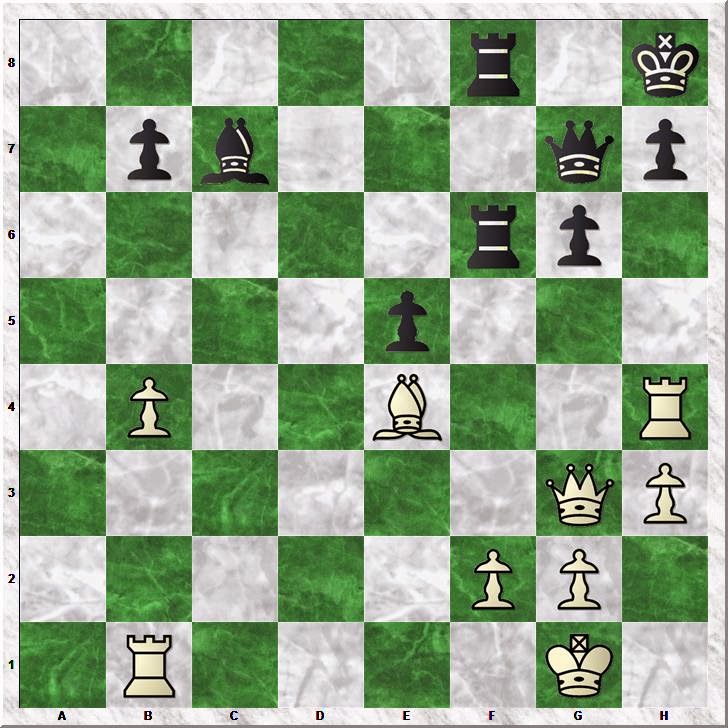

White to move

39.g3 Rg8 40.Qc8 Bb6 41.Qc3 Rxg3+

Exploiting the pinned f-pawn, and the continuation of tactical actions aimed at the rook on b1.

42.Kf1 Bd4 43.Qc8+ Rg8 44.Qc4 Rh1+ 45.Ke2 Rxb1

Black wins the rook

46.Rxd4

White takes a bishop in exchange.

46...Rb2+

46...exd4 appears to lead to a draw by repetition due to perpetual checks by White's queen.*

47.Rd2 Rxd2+ 48.Kxd2 Rd8+ 49.Ke2 Qh6 50.Qc3 Qg7 51.Be4 Kg8 52.Qb3+ Kf8 53.Qf3+

Black to move

Again, perpetual check appears to be a resource for White.

53...Qf7 54.Bxb7 Qxf3+ 55.Kxf3 ½–½

After three games without gaining a clear advantage with White, the Frenchman will find his way to victory in game 4 (see "McDonnell Blunders").

*It is my intention to go through these games and write my own comments without reference to engine analysis. I will check my analysis after completing a pass through all games.