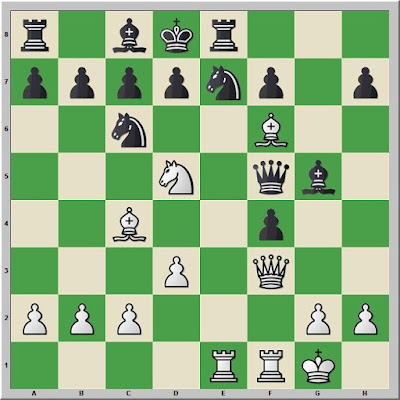

White to move

Digging deeper into Greco’s output through Professor Hoffman, The Games of Greco (1900) and William Lewis, Gioachino Greco and the Game of Chess (1819), shows that Greco had improved upon Black’s play in some variations on the game that led to this position.

Those improvements were the subject of my chess lesson with some students earlier this month. Greco’s variations in this and other games lead one to suspect that he methodically sought to improve the defense in the short miniatures by which he is principally remembered. But, as I have noted in prior posts, these variations—better games—are absent from databases, although present in the books by Lewis and Hoffman.

Further study since presenting the lesson to my students has revealed that the exercise in Checkmates and Tactics was presented to Giacomo Buoncompagno, the Duke of Sora, by “an exceptional player” (more than likely Giulio Cesare Polerio). A Spanish manuscript kept in the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence dated in the last quarter of the sixteenth century presents the position and a comment about its presentation to the duke. Two Italian manuscripts (Elegantia and Regole) from the same time period offer the game, but only Riccardiana has the story.

The sixteen move game, thus, should be considered the work of Polerio, not Greco. It would take much time and travel to examine these manuscripts, but others have done so. Their work has been compiled into a useful table: "Openings and Games of the Classical Era of Modern Chess," in Peter J. Monté, The Classical Era of Modern Chess (2014), 439-530; the game in question here appears on 503.

At some point in Rome, Greco had access to some manuscripts containing Polerio’s work and made copies. In his 1620 manuscript dedicated to an unnamed cardinal of Casa Orsini, Greco wrote that Black had an alternate defense in this game. Improvements to Black’s play appear in four manuscripts a few years later—Grenoble (1624), Paris (1625), Orleans (undated), and Godolphin (undated, but possibly 1623).

As I have repeatedly emphasized on Chess Skills, Greco's games are poorly known because his best work does not appear in databases. In this case, Greco is credited with a composition by Polerio that he criticized and improved in his own work.

Here, then, is Greco's main (best) game from this opening with Polerio's and Greco's other work as variations.

Those improvements were the subject of my chess lesson with some students earlier this month. Greco’s variations in this and other games lead one to suspect that he methodically sought to improve the defense in the short miniatures by which he is principally remembered. But, as I have noted in prior posts, these variations—better games—are absent from databases, although present in the books by Lewis and Hoffman.

Further study since presenting the lesson to my students has revealed that the exercise in Checkmates and Tactics was presented to Giacomo Buoncompagno, the Duke of Sora, by “an exceptional player” (more than likely Giulio Cesare Polerio). A Spanish manuscript kept in the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence dated in the last quarter of the sixteenth century presents the position and a comment about its presentation to the duke. Two Italian manuscripts (Elegantia and Regole) from the same time period offer the game, but only Riccardiana has the story.

The sixteen move game, thus, should be considered the work of Polerio, not Greco. It would take much time and travel to examine these manuscripts, but others have done so. Their work has been compiled into a useful table: "Openings and Games of the Classical Era of Modern Chess," in Peter J. Monté, The Classical Era of Modern Chess (2014), 439-530; the game in question here appears on 503.

At some point in Rome, Greco had access to some manuscripts containing Polerio’s work and made copies. In his 1620 manuscript dedicated to an unnamed cardinal of Casa Orsini, Greco wrote that Black had an alternate defense in this game. Improvements to Black’s play appear in four manuscripts a few years later—Grenoble (1624), Paris (1625), Orleans (undated), and Godolphin (undated, but possibly 1623).

As I have repeatedly emphasized on Chess Skills, Greco's games are poorly known because his best work does not appear in databases. In this case, Greco is credited with a composition by Polerio that he criticized and improved in his own work.

Here, then, is Greco's main (best) game from this opening with Polerio's and Greco's other work as variations.

Greco, Gioachino

Analysis, London? c.1623

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 g5 4.Bc4

4.Nc3 c6 5.Bc4 h6 6.d4 d6 7.h4 Bg7 is the sequence in Polerio's mss--see move 15.

4...Bg7 5.d4 d6 6.Nc3 c6 7.h4 h6 8.hxg5 hxg5 9.Rxh8 Bxh8

The last move in Primo, an undated Greco manuscript (likely 1619). Greco notes that Black remains with a pawn up.

10.Ne5

Several posters on chessgames.com have noted that this move is an error, giving Black a clear advantage

10...dxe5 11.Qh5 Qf6 12.dxe5 Qg7

12...Qg6 offers Black chances, too, but the text is better.

13.e6 Nf6

13...Bxe6 is suggested on chessgames.com

14.exf7+

This position appears as a diagram in Lewis 1819

4.Nc3 c6 5.Bc4 h6 6.d4 d6 7.h4 Bg7 is the sequence in Polerio's mss--see move 15.

4...Bg7 5.d4 d6 6.Nc3 c6 7.h4 h6 8.hxg5 hxg5 9.Rxh8 Bxh8

The last move in Primo, an undated Greco manuscript (likely 1619). Greco notes that Black remains with a pawn up.

10.Ne5

Several posters on chessgames.com have noted that this move is an error, giving Black a clear advantage

10...dxe5 11.Qh5 Qf6 12.dxe5 Qg7

12...Qg6 offers Black chances, too, but the text is better.

13.e6 Nf6

13...Bxe6 is suggested on chessgames.com

14.exf7+

This position appears as a diagram in Lewis 1819

Black to move

Having inherited this miniature from Polerio's writings, Greco sought to improve Black's defensive efforts. He offers two better moves for Black--Ke7 and Kd8 and carries each forward with a plausible line.

a) 14...Ke7

14...Kf8?? leads to the diagram at the top of the article.

15.Bxf4 Nxh5

15...gxf4 16.Qc5# appears in Polerio's manuscripts.

15...Ke7 is still possible 16.Bxg5+-.

16.Bd6# Is the line in the databases and the main game in Hoffman and Lewis.

15.Qe2 Be6

Black has better moves, such as Bg4, but most of Greco's line offers the best moves for both sides.

16.Bxe6 Kxe6

So far, Black is slightly better, but White has active play against a vulnerable king.

17.Qc4+ Ke7 18.Qb4+ Kxf7 19.Qxb7+ Nbd7 20.Qxa8

Three of Greco's extant manuscripts end here, as do Lewis and Hoffman. David Levy & Kevin O'Connell, Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Vol. 1 1485-1866 (1981) makes the contents of Hoffman accessible in algebraic notation. Francis Beale, The Royall Art of Chesse-Play (1656) also ends here.

Perhaps Greco thought that the win of the rook was sufficient for the line. However, he extended analysis five moves longer in what became one of his more obscure manuscripts. According to Monté, the manuscript was believed to have been dedicated to Sir Francis Godolphin. Tassilo von der Lasa acquired it in 1856 and still had it in 1897, but after his death, its whereabouts became unknown until Alessandro Sanvito found it in a collection in Poland.

Black has better moves, such as Bg4, but most of Greco's line offers the best moves for both sides.

16.Bxe6 Kxe6

So far, Black is slightly better, but White has active play against a vulnerable king.

17.Qc4+ Ke7 18.Qb4+ Kxf7 19.Qxb7+ Nbd7 20.Qxa8

Three of Greco's extant manuscripts end here, as do Lewis and Hoffman. David Levy & Kevin O'Connell, Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games, Vol. 1 1485-1866 (1981) makes the contents of Hoffman accessible in algebraic notation. Francis Beale, The Royall Art of Chesse-Play (1656) also ends here.

Perhaps Greco thought that the win of the rook was sufficient for the line. However, he extended analysis five moves longer in what became one of his more obscure manuscripts. According to Monté, the manuscript was believed to have been dedicated to Sir Francis Godolphin. Tassilo von der Lasa acquired it in 1856 and still had it in 1897, but after his death, its whereabouts became unknown until Alessandro Sanvito found it in a collection in Poland.

Black to move

20...Qh6 21.Qxa7 Qh1+ 22.Ke2 Qxg2+ 23.Qf2 Qxf2+

23...f3+ Black is slightly better.

24.Kxf2

Only now White is better, although what Greco thought is not clear. As the Godolphin manuscript would likely have been created in London, and is the most length analysis, a date of 1623 seems plausible.

With such a game, modern chess players armed with the latest Stockfish might still find faults in his analysis, but it should be clear that his strength exceeds the conclusions that are drawn when we associate him with Polerio's unacknowledged work.

Variation b is more clearly dated to 1624.

23...f3+ Black is slightly better.

24.Kxf2

Only now White is better, although what Greco thought is not clear. As the Godolphin manuscript would likely have been created in London, and is the most length analysis, a date of 1623 seems plausible.

With such a game, modern chess players armed with the latest Stockfish might still find faults in his analysis, but it should be clear that his strength exceeds the conclusions that are drawn when we associate him with Polerio's unacknowledged work.

Variation b is more clearly dated to 1624.

b) 14...Kd8

In this line, Greco's analysis is less precise. Although 14...Ke7 appears to give Black an advantage, with best play 14...Kd8 is equal.

In this line, Greco's analysis is less precise. Although 14...Ke7 appears to give Black an advantage, with best play 14...Kd8 is equal.

White to move

15.Qxg5

A nice deflection!

15...Qxg5 16.f8Q+ Kd7?

An error.

16...Kc7=

17.Qxh8

17.Bxf4!! Stockfish 17...Qxf4 18.Rd1+ Nd5 19.Qxf4

17...Qxg2 18.Qxf6 f3

White to move

19.Qf7+

19.Be6+!

19...Kd6

19...Kd8 is more stubborn.

20.Bf4+

20.e5+ Kc5 21.Be3+ Kb4 22.a3+ Ka5 23.b4# appears in Antonius van der Linde, De Kerkvaders der Schaakgemeente (1875).

20...Kc5 21.Na4+ Kb4

21...Kd4 22.c3+ Kxe4 23.Nc5# variation in Greco

22.Bd2+ Kxa4 23.b3+ Ka3 24.Qe7+ Kb2 25.Qe5+ Ka3

25...Kxc2 26.Rc1# variation in Greco

26.Bc1+ Kb4 27.c3#

This line and variations appears in two Paris manuscripts: Grenoble (1624) and Paris (1625), as well as the undated Orleans manuscript that appears to be copied from the Paris ms. While less precise, I could see extracting some checkmate exercises for my students from this variation.