The main line appears to be 1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 (the signature move of the Falkbeer Counter-gambit) 3.exd5 e4 (the topic of Falkbeer's 1850 article) 4.d3 Nf6 and then White has four main options.

a) Nc3

b) Qe2

c) Nd2

d) dxe4

According to John Shaw, The King's Gambit (2013), "White has excellent chances of an edge in the traditional main lines" (560). The Falkbeer "has become something of a museum piece at the highest levels," according to Neal McDonald, The King's Gambit: A Modern View of a Swashbuckling Opening (1998). Even so, Dmitrij Jakovenko has played it as recently as the 2014 Russian Championship.

|

| My Round Four Opponent |

The oldest game in the ChessBase database with Black's 3...e4

Anderssen,Adolf -- Falkbeer,Ernst Karl [C32]

Berlin m3 Berlin, 1851

1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 3.exd5 e4 4.Bb5+ Bd7 5.Qe2 Nf6 6.Nc3 Bc5 7.Nxe4 0–0 8.Bxd7 Nbxd7 9.d3 Nxd5 10.Nf3 Re8 11.f5 Bb4+ 12.Kf2 N7f6 13.g3 Qd7 14.c4 Nxe4+ 15.dxe4 Nf6 16.e5 Qxf5 17.Kg2 Rad8 18.a3 Bd6 19.Rd1 Qh5 20.c5 Rxe5 21.Qxe5 Qg4 22.cxd6 Re8 23.Qxe8+ Nxe8 24.d7 Qe4 25.d8Q Qc2+ 26.Bd2 1–0

Two memorable historic games.

Schulten,John William -- Morphy,Paul [C32]

New York blindfold m New York, 1857

1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 3.exd5 e4 4.Nc3 Nf6 5.d3 Bb4 6.Bd2 e3 7.Bxe3 0–0 8.Bd2 Bxc3 9.bxc3 Re8+ 10.Be2 Bg4 11.c4 c6 12.dxc6 Nxc6 13.Kf1 Rxe2 14.Nxe2 Nd4 15.Qb1 Bxe2+ 16.Kf2 Ng4+ 17.Kg1 Nf3+ 18.gxf3 Qd4+ 19.Kg2 Qf2+ 20.Kh3 Qxf3+ 0–1

Rosanes,Jacob -- Anderssen,Adolf [C32]

Breslau m Breslau, 1862

1.e4 e5 2.f4 d5 3.exd5 e4 4.Bb5+ c6 5.dxc6 Nxc6 6.Nc3 Nf6 7.Qe2 Bc5 8.Nxe4 0–0 9.Bxc6 bxc6 10.d3 Re8 11.Bd2 Nxe4 12.dxe4 Bf5 13.e5 Qb6 14.0–0–0 Bd4 15.c3 Rab8 16.b3 Red8 17.Nf3 Qxb3 18.axb3 Rxb3 19.Be1 Be3+ 0–1

My fourth round opponent started with the Bird, which I met with the From, then we transposed into the King's Gambit and the Falkbeer. That is exactly how one of my worst tournament games ever began two years ago, except that I had White (see "Knowing Better").

Tito Tinajero (1614) -- James Stripes (1845) [C32]

25th Collyer Memorial Spokane Valley (4), 26.02.2017

1.f4 e5 2.e4 d5 3.exd5 e4 4.Nc3

4.d3 is considered best. 4...Nf6 5.dxe4 Nxe4 6.Nf3 Bc5 7.Qe2 "theory and practice have demonstrated with a high degree of certainty that White will obtain an advantage" (Shaw, 585).

4...Nf6 5.Bb5+

I expected 5.d3, which is the main line. Shaw mentions 5.Bb5 as a means of avoiding established theory. It's certainly a worthy move at the club level.

5...c6

5...Nbd7 or 5...Bd7 were options. Because I needed to win, I was happier accepting weaknesses in pawn structure than offering minor piece exchanges. Later, however, concrete analysis forced me to consider some exchanges.

6.dxc6 bxc6 7.Bc4

Black to move

7...Bg4?!

7...Bc5 seems better and was played in the only game in PowerBook 2016 with 5.Bb5+. That game continued 8.d4 Qxd4 9.Qxd4 Bxd4 10.Nge2 Bb6 11.Na4 Ba6 12.Nxb6 axb6 13.Bb3 0–0 14.h3 c5 15.a3 e3 16.Bxe3 Re8 17.Kf2 Ne4+ 18.Kf3 Bb7 19.Rhe1 Nd7 20.Ng3 Ndf6 21.Nxe4 Nxe4 22.Ke2 Ba6+ 23.Kf3 Bb7 24.Ke2 Ba6+ 25.Kf3 Bb7 26.Ke2 ½–½ Metz,H (2275) -- Baburin,A (2530) Liechtenstein 1993

8.Be2

8.Nge2 was worth considering.

8...Be6

8...Bf5 9.d3 Qb6 10.dxe4 Bxe4 was played in Richter,E -- McAloon,J, Ca'n Picafort 1992, which White won in 36 moves.

9.d3 Bb4 10.Bd2

Black to move

10...exd3

I first thought of 10...e3, as Morphy played against Schulten, but my c-pawn makes a critical element of Morphy's attack impossible.

I missed an opportunity: 10...Qd4! 11.Qc1 (11.dxe4? Bc5 12.Qc1 Qf2+-+) 11...Nbd7 and Black's pieces are more active.

11.Bxd3 Qb6?

I should have castled, but failed to anticipate White's next move.

12.f5 Bd5

I spent twenty minutes on this move.

13.Nxd5 Nxd5

During that twenty minutes, I thought that I would play 13...Bxd2+, but now spent another five minutes considering whether that was best. Although several of my moves in this game were not best, the time that I invested and the care taken are indicators that I was taking the game seriously. I was playing the board, not my opponent. I was not making the sort of hasty moves that cost me a draw on Saturday (see "Stronger King").

14.Qe2+

Black to move

14...Kf8

I spent another thirteen minutes on this move. I considered 14...Kd8, as well as several other options that seemed to fail tactically. I wanted to castle, but blocking the check and the castling seemed to drop a piece after White drove the knight away. Of course, White would need to castle first or face a skewer along the e-file. Blocking the check with the knight seemed to be going backwards.

My chess engine prefers 14...Kd8, which I rejected because it seemed too easy for White to move the bishops, producing a discovered attack against my king. If I could calculate as well as a computer, I might have been able to assess these dangers. 15.0–0–0 Re8 16.Qf1 Nd7 and Black is equal, according to Stockfish.

14...Kf8 is the computer's second choice.

15.0–0–0 Nd7

Stockfish prefers 15...Be7, which would have been consistent with my earlier plan to avoid exchanges. But, now, I sensed the need to catch up in development. Despite my sacrifice of a pawn for activity, my opponent's pieces seem more active.

16.Bxb4+ Qxb4 17.Bc4?

17.Qd2 and White retains the edge.

17...Re8

The game is equal.

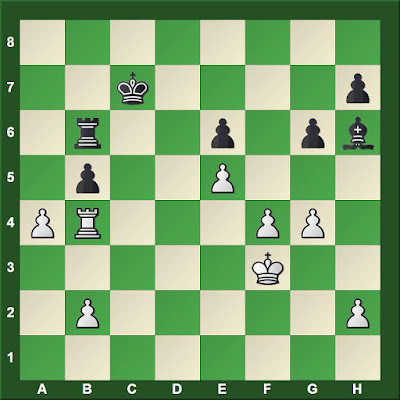

White to move

18.Qd3??

18.c3 Nxc3 19.bxc3 Qxc3+ 20.Qc2 Qa1+= and Black forces a draw. I likely would have played something else and been worse.

After 17 moves, my opponent had 1:15 remaining to my 45 minutes. Being behind thirty minutes on the clock might have motivated me to cut my losses and bail. Happily, he spent four minutes finding a horrendous move that I quickly exploited.

18...Ne5 19.Qf1 0-1

After making this move, my opponent tipped his king before I could play 19...Nxc4.

It may be worth my time to find another line against the King's Gambit, or to meet the Bird with something other than the From. Against 1.e4, I usually play the French.