I read about the three pawns problem in The Oxford Companion to Chess, 2nd. ed. (1996) by David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld. They assert that it had been known for two centuries or longer before solved by József Szén in 1836. Hooper and Whyld present a portion of Szén's analysis, which I was able to read in its entirety at least a decade ago. But, they also noted it had been examined by Pietro Carrera in 1617 and was likely known earlier (420).

Peter J. Monté, The Classical Era of Modern Chess (McFarland 2014), a book I acquired last week (see "Monumental Scholarship"), fills in some details. A small untitled manuscript discovered in 1939 by chess historian Adriano Chicco contains what might be the oldest extant version of the problem. This MS was authored by Count Annibale Romei of Ferrara. Romei's date of birth is unknown, but his death in October 1590 seems clear. Chicco dates the MS within the years 1565-1568, making it "the oldest known work on modern chess written extensively by an Italian author" (Monté, 188).

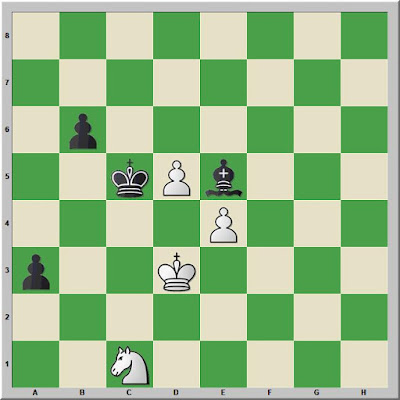

Romei's MS contains this "Subtlety" (Monté, 193).

White to move

After 1.a6 king moves 2.b8Q Kxb8 3.c6, we reach a position that should be well-known today (see "Floating Square").

The next manifestation of the problem mentioned by Monté is Carrera's (Monté, 313).

Black to move

Successfully stopping Black's three connected passed pawns leads to stalemate, which under some rules in Carrera's day is a win, or a half-win, depending on where the game is being played.

Monté also notes that José Antonio Garzón believes that Francesch Vicent presented a version of the three pawns problem to the Ferrarese nobility about 1502. The argument appears in José Antonio Garzón, El regreso de Francesch Vicent. La Historia del Nacimiento y la Expansión del Ajedrez Moderno (Valenciana, 2005); English translation by Manuel Pérez Carballo, The return of Francesch Vicent : the History of the Birth and Expansion of Modern Chess (Valenciana, 2005). The website Valencia Origen del Ajedrez 1475 has generously made the critical chapter of the author's key argument available for reading in English online. In that chapter Garzón systematically presents every known manuscript preceding Vicent's to argue that modern chess did not develop over hundreds of years, as many historians have assumed, but emerged quickly in Valencia about 1475, and from there spread very rapidly across Spain and the Italian peninsula. Monté seems convinced, or nearly so.

Following Carrera, the three pawns problem next makes its appearance in the position that I posted two weeks ago ("A Greco Composition"). I found this position in Antonius von der Linde, Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels (1874). Monté fills in some details. It appears in three Greco MSS: Grenoble MS (1624), the Paris MS (1625), and the Orléans MS--undated, but likely 1624-1625 based on its strong similarity to the other two--my observation (Monté, 352).

White to move

White can create a position that is losing with 1.Kd1, but there is no reason to play such a move except to taunt your opponent. If Black is on move, the position takes on much of the characteristics of Szén's, where the player on move has a forced win. I gave Black the move and played Greco's against Stockfish on my iPad a week or so ago. As Hooper and Whyld eloquently express. "understanding of the analysis is not without practical value" (420).

I presented Szén's position in 2009 ("Pawn Wars"), but as some readers will not be able to view the images in that post (I was using an external image hosting service), I repeat it here.

White/Black to move (and win)

In my view, all of these positions are worthy of study and practice.