In some cases, especially with simple pawn endgames in chapter 1 of Chess Fundamentals, I believe that Capablanca provides the necessary resources in the explanations that he offers. Still, I have seen others struggle. They need more help. Capablanca recommends a teacher.

When Capablanca wrote Chess Fundamentals (he was checking the proofs in England in 1920 while negotiating conditions for the World Championship Match that took place in March and April 1921--see "WCC Havana 1921" in this site's index), there were fewer resources than we have today. I believe the standard endgame book then was Johann Berger, Theorie und Praxis der Endspiele (1890), a book in the German language that was probably not readily available or accessible to the majority of Capablanca's readers.

Today, however, we have an abundance of books, websites, YouTube, ready access to engines, and even tablebases. The danger to the student stems not from lack of help, but rather too much help. Easy access to answers cause many to fail to develop self-reliance. Capablanca's call to develop the habit of working things out may offer a more certain formula for strengthening a player's skills.

I often claim that I have zero natural ability at chess, but that I have learned a modest amount from books (see "My First Chess Book"). Many years ago when I started reading chess books, I found much that was confusing. The book I remember most clearly is Irving Chernev, The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (1955). Often it was not evident to me why a game ended. Sometimes Chernev explained the reason, but even then I had questions. I sought answers to my questions by moving the pieces on a chess board, exploring variations. Certainly, with so little skill at the time, most of my fantasy variations were rubbish. Even so, the effort developed a habit of thinking for myself about chess.

The past few days I've found myself back in the classroom, seeking understanding. I started playing some bishop endgames against the computer on chess.com. Failure in my first effort got me hooked. My time struggling through five positions against the silicon monster engages me for hours every day. At the Learn/Endgames/Minor Pieces/Bishops tab on chess.com, there are five practice positions. To see the second one, you must checkmate the computer in the first. The first is simple and takes me from 12 to 24 seconds most times.

The second one varies in difficulty, depending on how the engine plays.

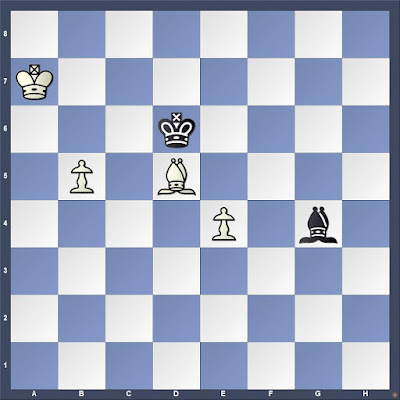

White to move

|

| Number Two |

I always play this move. It might be best.

1...h5 2.f3

Now the engine has played 2...a5, 2...Ke7, and 2...Kc6 most regularly. 2...Kc6 has proven most testing but I am reliably winning most of the time. Success grants me the opportunity to see number three.

White to move

|

| Number Three |

1.c5 dxc5 2.Bc4 Bg4 3.Kxe5 Ke7 4.Kd5 Kxf7 5.Kxc5 Ke7 (the computer threw me a curve with 5...Kf6 at least once) 6.Kxb4 Kd6 7.Bd5

Black to move

The computer has played at least five different moves here.a) 7...Bf3 proved challenging the first time I saw it. That line now often continues 8.Ka5 Be2 9.b4 Bg4 10.Kb6 Bh3 11.b5 Bg4 12.Ka7 and the computer must give up the bishop for my b-pawn.

Black to move

12...Kc5 has given me trouble when I am moving too fast, which the exercise encourages by tracking total time for the series and making me play simple checkmates all the way to the end. Sometimes I underpromote to practice bishop and knight or two bishop checkmates.13.Bc6 Bc8

Here, 14.b6?? fails, but both 14.Kb8 and 14.e5 succeed.

I have seen most of the computer's responses several times, but this morning's effort presented me with a position I did not recall seeing before.

b) 7...Bd7 8.Ka5 Kc7 9.Kb4 Kb6

White to move

10.Kc4!There is more than one way to get rid of Black's bishop.

10...Be8 11.Kd4 Kb5 12.e5 Kb4 13.Ke4 Kc5

White to move

14.Bg8 Bc6+ 15.Kf5 Kb4 16.Kf6 Kc3 17.Bc4 Bd7This move is Stockfish surrendering it seems.

White to move

18.e6 Bc6 19.Kf7 Black must give up the bishop for the e-pawn. A few moves later, I underpromoted the b-pawn to a bishop. When I was nine or ten moves from mate, I made a hasty move that stalemated the engine. Now, I must start over at number one. I've played number five half a dozen times and have some ideas how to proceed. My current problems are two: 1) the engine lures me into a pawn ending that is lost foe me, and 2) I fail two, three, and four too often.

Have you tried these exercises? How did you do?

Not sure if you are aware of this, but the tactics site ChessTempo, has a "Book Section" where some books are available as interactive books to play through. The free book which is available for one to try the system is Capablanca's Chess Fundamentals.

ReplyDeleteThe Link is https://chesstempo.com/chess-books/chess-fundamentals/read/165. I don't think you need to be a member to use it ( I am a member so its available to me), however its worth trying.

Thanks. Yes, I am a paying member of ChessTempo and received a notice when they added this feature. I've been sending people there the past few months.

Delete